How Hercules Became Antiquity’s Brawny, Brainless Himbo

His long journey to a muscle-bound Disney babe belting out ballads

In DepthIn Depth

Image: Photography by Jeremy Villasis

In 1997, Disney turned its attention to one of the most recognizable heroes in the history of western civilization: Hercules, son of Zeus, famous for his 12 larger-than-life, impossibly difficult labors. Transforming Hercules into a family-friendly Disney protagonist required some significant changes from the original source material. Disney’s Hercules had the shoulders of an ox, a heart of gold, and zero brains. A complete himbo, in other words. I am far from the first person to make this observation, using this precise term. There have been dozens and dozens of tweets about Hercules as a himbo; “I like disney’s hercules bc it’s a love story about a teen himbo and a jaded 35 year old woman,” goes my favorite. But the figure of Hercules is millennia older than the Disney portrayal—and his journey to himbohood has been a strange and winding one.

Herakles, as the Greeks called him (the Romans gave us Hercules) would have been fairly well known across the world of Classical period Greece, the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. Of course, the ancient Greeks meant something very different—and very specific—by the term “hero.” Professor Gregory Nagy has been hammering this into the heads of undergraduates (including yours truly) since the late 1970s with his long-running, perennially popular Harvard course, The Ancient Greek Hero. For one thing, Hercules was a figure of hero worship. A Greek hero wasn’t necessarily a hero because he was virtuous or morally perfect. A Greek hero was semi-divine and thus beyond the merely mortal. A Greek hero was excessive, Hercules in particular. He also wasn’t a hero through righteous deeds, but death. That’s because heroes were a specific sort of cult figure in the ancient Greek world.

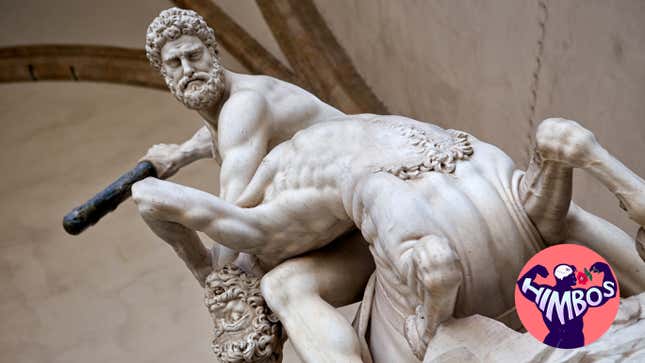

But beyond his existence as a figure of hero worship, Herakles would have been well-known across the world of ancient Greece as a figure from storytelling. Known for his feats of strength, he was often represented as toting a club and wearing the skin of the Nemean Lion, a vicious and powerful lion which he slew in the first of his famous labors. But that’s not to say that the ancient Greeks thought Herakles was dumb, as Columbia’s Elizabeth Scharffenberger, who specializes in Athenian tragedies, explained to me.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-