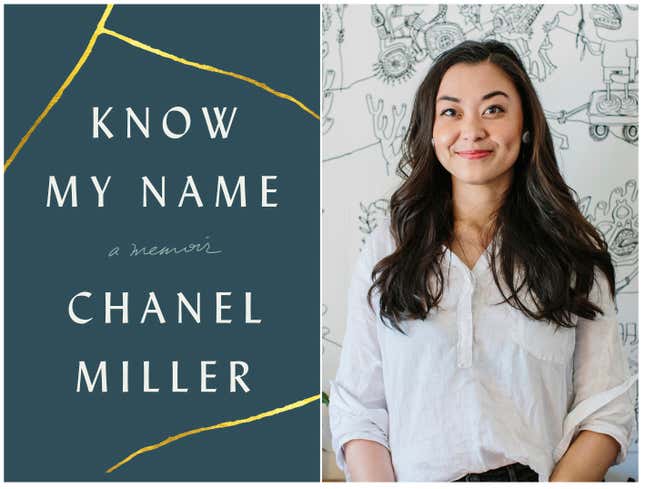

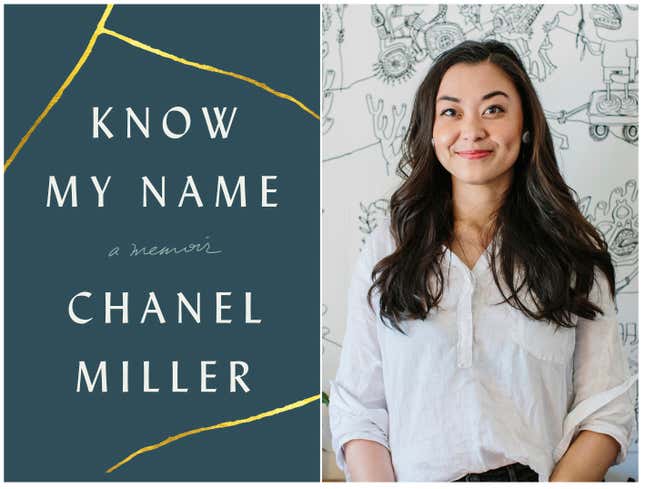

The story of Emily Doe is a familiar one. For a culture inundated with stories about sexual assault, the details of Emily Doe’s sexual assault are especially horrific. But the story itself is so familiar that the contours of what happened have entered the collective feminist memory, been absorbed and made almost mythical.

The oft-repeated story goes something like this: In January of 2015, Stanford student Brock Turner was outside of a fraternity party sexually assaulting an unconscious woman when two Swedish graduate students saw what was happening and intervened. The case went to trial and Turner was convicted of three felonies, including assault with the intent to commit rape. Judge Aaron Persky sentenced Turner to six months in county jail, probation, and required him to register as a sex offender. During the year surrounding the trial, the victim was only identified as Emily Doe—a faceless entity known not for the life she had before the attack, but for the details surrounding it. Her victim impact statement, originally published by Buzzfeed in 2016, went viral almost instantly—a grim traffic victory. Addressed clearly to Turner, she writes “You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside me, and that’s why we’re here today.” What proceeds is emotional, angry, and damning in detail. The candor in her statement struck a nerve, for here was a survivor’s story that gave shape to the bullet point details published in the press. This was proof that there was a real person behind the facts as presented, but she was still Emily Doe, still an abstraction.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-