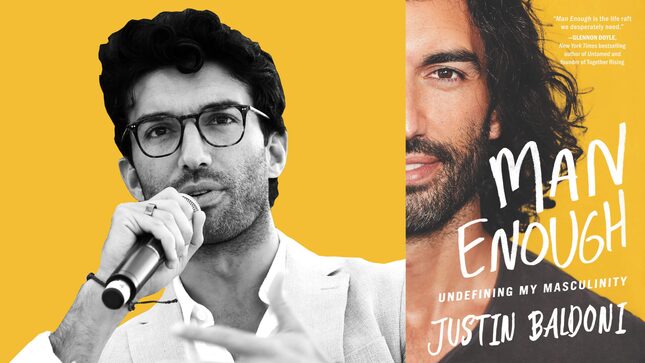

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, HarperCollins and Blackstone Publishing)

Actor and director Justin Baldoni’s new book, Man Enough: Undefining My Masculinity, is remarkably honest about its limitations. “I’m not sure if there is anything really revolutionary in this book,” he writes in the opening line of the introduction. “Unique maybe?” he asks, even as he appears to question that. The book is, Baldoni writes, “a messy, vulnerable exploration of manhood,” in which uncertainty is a selling point. Best known for playing reformed womanizer Rafael on Jane the Virgin, Baldoni has recently emerged as a celebrated figure of masculine vulnerability—and Man Enough is the packaging of that ethos.

During the 2o17 TEDWomen, a conference meant to highlight “the power of women and girls,” Baldoni stepped onstage to announce that he had been living in a state of conflict “with who I feel I am in my core” and “who the world tells me as a man I should be.” He was fed up with our “broken definition of masculinity” and tired of trying to be “man enough.” Baldoni confessed to the audience, “I’ve been pretending to be strong when I felt weak, confident when I felt insecure and tough when really I was hurting,” he said. “And I can tell you right now that it is exhausting trying to be man enough for everyone all the time.” Vulnerability was a key part of his prescription.

Men, he said, needed to learn to “embrace the qualities that we were told are feminine in ourselves.” As he put it: “Are you brave enough to be vulnerable? To reach out to another man when you need help? To dive headfirst into your shame? Are you strong enough to be sensitive, to cry whether you are hurting or you’re happy, even if it makes you look weak?” The speech spread far and wide, with women’s magazines profiling Baldoni’s attempt to “redefine” masculinity. On YouTube, women commenters applauded his sensitivity, occasionally offering up the sentiment that real men express their feelings. Men weighed in with their own struggles with repressing emotions alongside the dictum of “boys don’t cry.”

Man Enough is the inevitable outgrowth of this viral speech. At points, it movingly details his struggles within the straight-jacket of masculine expectation, including being exposed to porn under intense social pressure as a confused 10-year-old. In a heartbreaking passage, he describes a traumatic encounter with a teenage girlfriend who violates his clearly stated sexual boundaries (what he describes reads to me as rape, although he does not use the term). Baldoni details his experience with body dysmorphia while being routinely asked to appear shirtless on TV. He writes about telling his castmates that he felt too insecure to take his shirt off and being laughed at in response.

The book honors emotions and tenderness in ways that are often devastatingly cut off for men. Man Enough is valuable as a masculine counterexample, but it ultimately vaunts feelings at the expense of meaningful analysis. Although Baldoni has identified himself as a feminist—and the TED website calls him an “outspoken feminist”—the book isn’t interested in the movement and distances itself from what he calls “political agendas.” Trapped within the narrow confines of self-help, where feelings reign supreme, Baldoni’s approach to masculinity is a reminder that sensitivity can be a way to pre-empt critique; vulnerability can be a shield. Emotional appeals set the terms of debate (often, that there isn’t one). He’s already announced his insecurity, as well as the high stakes of his self-exposure, so any outside criticism may appear excessive or inappropriate. (Jezebel requested an interview with Baldoni, but his team “politely” declined.)

Feelings do not exist in a vacuum, though. The apolitical reclamation of emotion seems a way to make masculinity slightly more bearable for men. The potential for harm is especially pertinent in the Trump era, which through a certain lens is defined by the political enactment of men’s emotions to the detriment of women and other marginalized groups.

Baldoni admits that the book is “written by someone who sits at an intersection of power and privilege and who historically probably wouldn’t willingly choose to get this vulnerable, as there would seemingly be no benefit.” Then he asks: “Why try to tear down the walls in a system that has benefited me my entire life?” Among his answers are that it feels like the right thing to do. The very phrasing of the question is telling: tearing down the walls in a system implies an interest in maintaining that very system. Baldoni positions himself as purposefully apolitical: “I am not pushing any partisan belief system or agenda here. As a registered Independent, I don’t subscribe to any political ideology, and though I absolutely vote and participate in elections, I don’t talk publicly about who I am voting for.”

He wants to ensure “this book does not jump into what is currently considered ‘woke’ for the sake of wokeness” and believes we must “separate the masculinity conundrum from political agendas to do the nuanced self-work and necessary healing to successfully create space for the conversations to be had.” Although Baldoni dedicates a chapter to the subject of race and exploring his own white privilege—a chapter he admits that he wrote last, seemingly in response to the murder of George Floyd—he does not appear to appreciate how that privilege allows for the book’s foundational illusion of being able to separate “the masculinity conundrum” from politics.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-