Kissing Ass At Miki Agrawal's Butt-Con

Latest

Illustration: Jim Cooke

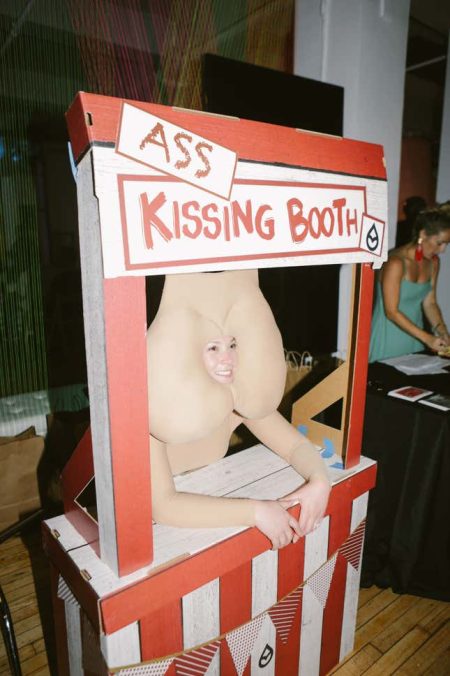

The first time I visit the “ass-kissing booth” at Butt-Con, the bizarre marketing party for entrepreneur Miki Agrawal’s latest venture, the ass asks me to kiss it. The booth is pinstriped and flimsy, a gag on the more chaste version you’d find at a country fair: A self-described “friend of Miki’s” is on her knees with a plush butt framing her face, holding the floppy appendage up to me. “Just the tip?” she asks. I decline.

The second time I visit the booth, a few hours into the event, Agrawal is with me, and she clarifies to this person dressed up as a butt that actually, the kiss isn’t literal—the ass is supposed to “kiss up” to me. Dutifully, the friend gazes up at me and tells me how pretty I am, what an excellent fashion sense I have, how great my vibes are, and that I’m the best person who ever walked the earth. I tell her only one of those things is potentially true. Agrawal turns to me and sets in on the pitch—the reason she’s packed a hundred-odd people into a Midtown loft to take ass selfies and nod sagely to advice about butt sex—which is that we have all been “deeply indoctrinated” to believe toilet paper is the answer, and Agrawal is going to make money reeducating us. Through her company, Tushy, she’s going to make the bidet sexy—she cites the iPhone as a design inspiration—and bust through our Puritanical squeamishness when it comes to talking about shit. “People are so uncomfortable talking about it,” she says. “There’s been no innovation.”

Agrawal is going to accomplish this, ostensibly, by doing what’s she done in the past—by being a gifted marketer who reimagines ordinary products as subversive social acts—without letting her penchant for boundary-crossing and “subversion” in the workplace slow her down again. She’s also going to rebrand herself as someone who, at her former company Thinx, was simply too revolutionary of a boss to be understood by the haters and the prudes. Which is why, earlier this month, members of the media and owners of Tushy’s “millennial” brand of bidet received an odd, pun-laden invitation to something called Butt-Con, the “inaugural butt-stuff convention,” promising an “immersive, interactive convention for the like-behinded.”

Less of a conference than a start-up party, pegged vaguely to butt stuff, the event took place on the sweaty fourth floor of midtown high-rise. A DJ spun the usual ass anthems while a handful of attendees learned how to twerk in a small wood-floored room. An art installation featuring a toilet sat next to vendors selling supplements for cleaner colon health. A Tushy-branded blow-up ass rose above the crowd, kissing the low ceiling; the porn star Asa Akira held a panel encouraging more comfortable anal sex—it’s about communication—while the 83-year-old Hattie Wiener, of the TLC show Extreme Cougar Wives, milled around squinting in gold and lace.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-