‘Mean Girl Feminism’ Argues That Being Sassy or Sarcastic Isn’t the Feminist Act White Women Think It Is

A new book by Dr. Kim Hong Nguyen dives into how white feminists are still, unsurprisingly, doing feminism wrong.

Photo: Shutterstock BooksEntertainment

We’re all familiar with the trope of the damsel in distress, but let me raise you one and introduce you to the “damsel in resistance.” Both patriarchy’s biggest problem and its biggest solution, the damsel in resistance is a mean white girl who breaks the mold of white femininity by being mean and uses that meanness to speak out against sexism, misogyny, and patriarchy itself. Both in real life and in pop culture, more than a few white feminists who’ve snarked their way up to the top come to mind: Succession’s Shiv Roy was quick to call her brothers, dad, and husband out on their sexist bullshit when it benefited her, and ultra-scammer Elizabeth Holmes didn’t exactly girlboss her way into Big Pharma without deliberately silencing whistleblowers (or letting her employees keep all of their blood, for that matter).

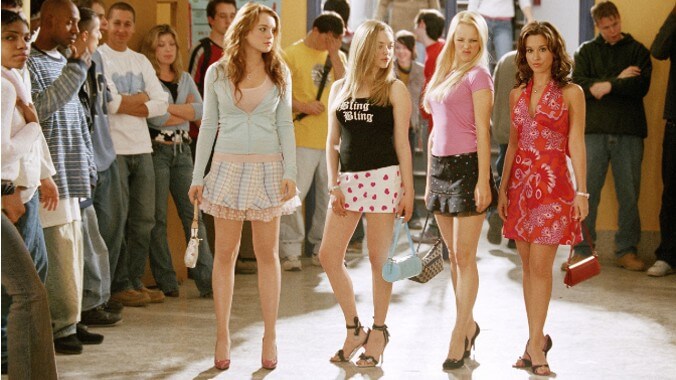

There’s only one problem: this meanness and the so-called feminist successes it brings (whether at work or in their social circles), come at a price. And more often than not, it’s for women of color and other marginalized people to pay. In her new book Mean Girl Feminism: How White Feminists Gaslight, Gatekeep, and Girlboss, associate professor of Communication Arts at the University of Waterloo Dr. Kim Hong Nguyen brings forth four distinct figures—the bitch (Great News’ Diana St. Tropez and the phenomenon on the Resting Bitch Face), the mean girl (Mean Girls’ Regina George and Cady Heron), the power couple (Hillary and Bill Clinton, and Gossip Girls’ Blair Waldorf and Chuck Bass), and the global mother (Laura Bush)—to show us how white feminists co-opt women of color’s performances of resistance (think: being bitchy or sassy) in order to maintain the cis-heteropatrial status quo. And, because they harm the very people of color they mimic, they end up being just as toxic as the white men they’re trying to gain equality with, becoming what Nguyen calls “better masters,” instead of advancing feminist agendas in any meaningful way.

In a tight 100 pages, Nguyen elucidates how denying that white women’s aggression is a form of violence and how “position[ing] that aggression as feminist” paves the way for mean girl feminism to extend the violence of white supremacy, capitalism, and much more.

Throughout the book, Nguyen walks us through an impressive cast of mean white feminists to demonstrate how some of North America’s most culturally beloved (and culturally hated) white women invoke mean-girl feminism to get what they want. Whether it’s using their relationships with white men to capitalize on their power or weaponizing the suffering of women and girls of color to justify war, these white feminists do more harm than good in their efforts to achieve their own personal gain. All while being praised for carrying the feminist torch forward.

During our conversation, Nguyen said that writing this book was fueled by both anger and grief. But in confronting these negative feelings, in addition to the “ugly aspects of feminism,” Nguyen presents us with what I read as a work of urgent hope—one that, if read in good faith by the feminists who need its message the most, could bring us closer to a truly liberatory intersectional feminist practice. This conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

JEZEBEL: I feel like I have to ask if you’ve seen the new Mean Girls movie.

Dr. Kim Hong Nguyen: I have not honestly. But it does seem to be having a moment. I think that we’re in a moment right now where Mean Girls resonates with a lot of people. And I think it’s because there’s a cultural interest in being ironic in the face of the power that white women and feminism have in society. I think that the original was a success because it captured a lot of what I call “white nonsense” about femininity, which is how white women do feminism. The way they do it is to increase their own visibility and popularity, and they do so often to their own detriment.

I was really interested in one of your main arguments in the book around white feminism fetishizing gender. Could you talk a little bit about what you mean by that and what the outcomes of this fetishization are?

So white feminism has supposedly gone through these waves. I came into academia as a third-wave feminist. [Third-wave feminism critiques] white feminism on the basis of race, class, sexuality, ability, etc. And so when I read the scholarship of white women, I’m starting with this very question: Are they writing in response to, or in account of, third-wave critiques? Is this white woman writer or scholar contending with race in addition to gender? More often than not, I’m finding that they’re not. They’re overly focused on gender, so much so that to them, everything hinges on gender without regard to other systems of power.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-