Parenting Is an Exercise in Triage

Latest

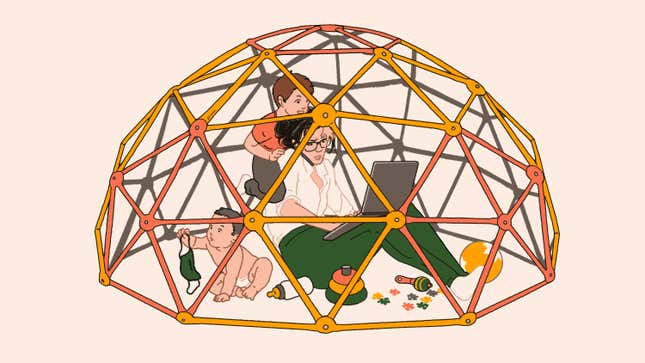

Image: Angelica Alzona

I’ve been promising my editor something about childcare during the coronavirus for at least a month. In normal circumstances, after years of blogging, a mid-length opinion piece requires a couple of days, maybe three for something particularly thorny. The difference, of course, is that until March, my toddler went to daycare, and now I’m trying to write to the sound of Dora the Explorer and I just got hit in the shoulder with an errant milk cup and had to stop writing and firmly remind my child not to throw things in the house, especially not toward the ceiling fan where it could rebound and land god knows where, breaking god knows what. This constitutes a very good day for a mother trying to hold down a job during the coronavirus pandemic, which has made it impossible for even the most privileged to ignore America’s complete failure to achieve even a minimally functional childcare system. And with the ravages of the virus threatening to jeopardize the broken patchwork we do have, it’s a make-or-break moment for the future of American women.

After several months of covid-19, parents are getting by with some combination of bribery, increasingly baroque entertainments (this is the year of the at-home caterpillar grow kit), immense amounts of screentime, and just letting their kids run wild, and most people aren’t lucky enough to work at a supposedly feminist website with a boss who is committed to working parents. But the simple fact is that kids are a lot of work, and even taking this as an opportunity to develop some independent play skills still requires keeping one ear out for trouble, all the time, the radar constantly scanning for disaster, any little blips disrupting hard-won concentration. I started the year with lots of big ideas and plans; now every workday is an exercise in triage, and, despite the proliferation of trend pieces, I have not been making any sourdough. I have begun to hate the Paw Patrol theme song, which never fails to make my shoulders tense as I start tallying the screen time total for the day, the week, the year, wondering just bad it is that we’ve overrun the recommended screentime every day since the pandemic began months ago.

The situation is getting worse as the novelty of the coronavirus wears off, even as cases continue to climb across the country and hospitals are flooded with patients, demonstrating that this virus is far from done with us. A recent guide to “Zoom etiquette” from the Wall Street Journal typifies the attitude that is beginning to take hold, urging everyone to turn on their cameras even as they discourage “lurkers,” i.e., children: “At many places, pets and children are no longer the cute intrusions they were in the early days of the pandemic.” A woman in San Diego has already filed suit against her former employer, alleging she was fired because her employers were unhappy at her juggling work and childcare. The drive toward reopening, even as many schools plan to go online-only, will only intensify the crunch, as many parents are expected to return to offices. And, of course, many parents never worked from home in the first place. Parents who work at grocery stores, in slaughterhouses, and at delivery companies have been there all along, doing the best they could for their kids.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-