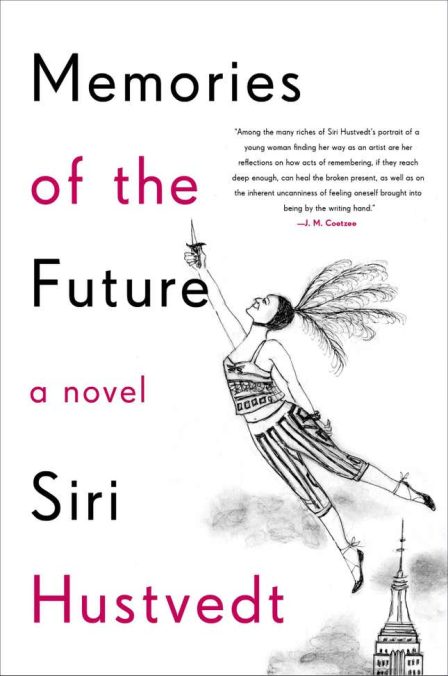

Siri Hustvedt’s seventh novel, Memories of the Future, contains several references to Baby Face, a 1933 film starring Barbara Stanwyck. Master of hardnosed wise-cracking, Stanwyck plays Lily Powers, a bored young woman working in her father’s bar. She is introduced to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche by an older patron, and a particularly memorable moment sees the young woman reading a paragraph from Will to Power which famously contains the phrase “Crush out all sentiment.” For Powers, it becomes a call to arms and signals her escape from her miserable situation, in which she is poor and constantly groped by her father’s clientele. She uses this hard-line thinking to scheme her way out of poverty, into comfortable housing, expensive jewels, and expansive furs. Though labeled a “hussy” by the high society she manages to enter, Stanwyck’s character remains, for the most part at least, focused on herself and her own happiness.

Though Hustvedt’s novel does not follow a plot that bears any resemblance to Baby Face, her inclusion of the film speaks to its interesting undercurrent: the ability of women to be, as the novel puts it “beastly and cold.” Of course, what it means for a woman to be either of those things is quite different from what it means for a man. In recent years, there have been several examples of difficult women who have graced our screens in their ambivalent glory, most recently the protagonists of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s projects Killing Eve and Fleabag. Hustvedt seeks to depict women who are more complex than simple narrative devices and pull at the threads of memory that are colored by the often difficult emotions women feel under patriarchy.

Hustvedt explores rage, revenge, and violence in the lives of a group of women brought together through the city of New York. Memories of the Future is written through the perspective of S.H. as an older woman reflecting on a year of her life when she moved to New York from her native Minnesota. The young S.H., a clever, flexible thinker who’s in love with writing and with words (and also nicknamed “Minnesota”), has come to the city to write a novel before beginning a Ph.D. program at Columbia. In this year she has gifted herself, she goes on a quest through literature, looking for a story for her “unformed hero.” While the novel includes many of young S.H.’s diary entries—a form Hustvedt has used before—the older S.H. reflects not only on what is contained therein, or in the small excerpts of the novel-in-progress, but on memory itself, reflecting on what has been either omitted or included in the records of her younger self.

In the opening pages, Hustvedt considers the differences of years through the process of writing: “I didn’t know then what I know now: As I wrote, I was also being written.” The character of S.H., in both youth and older age, is clearly enamored with reading, and with novels: Hustvedt refers to a coterie of classic novels and novelists from Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, to George Eliot, the “peerless” Charles Dickens, and, the most clearly beloved Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. In the young S.H.’s search, there is something of Quixote about her, as she seeks to transform her visions from reality into the elevated plane of fantasy. The genre that particularly interests the young writer is the mystery, and throughout the novel, scenes from the mystery story she is writing weave in and out of her diaries. The older S.H., much more widely read and clearly supremely knowledgable, gradually comes to reflect on her earlier love of mystery, and particularly of Sherlock Holmes with whom she—and of course Hustvedt herself—share initials. The mystery, the clues, reading and interpreting signs, this way of approaching the world fascinates the young S. H. and dominates her thinking as she first makes her way in the city.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-