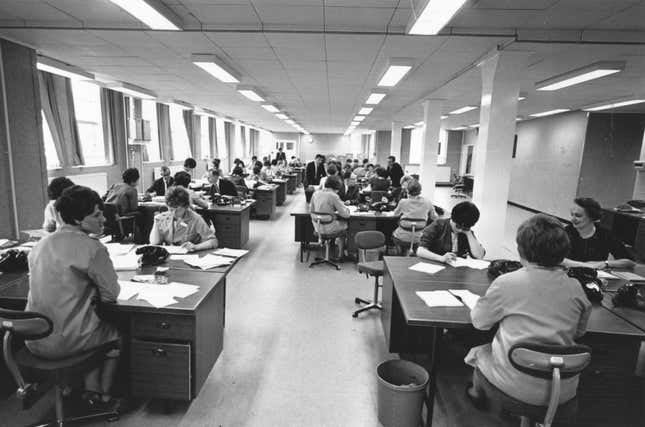

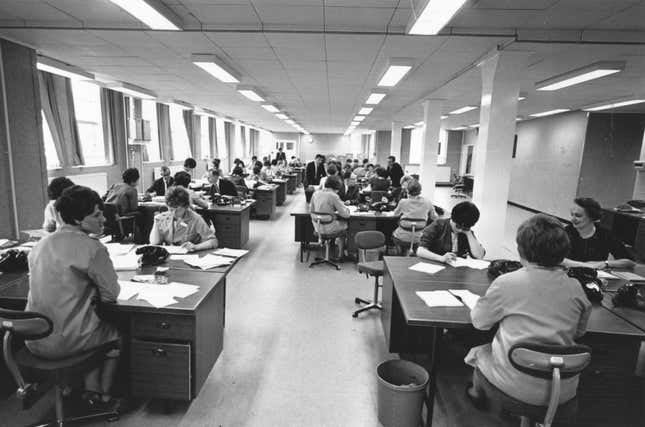

Some Black Women Want to Keep Working from Home Because It’s Microaggression-Free

Remote work hasn't solved all workplace problems, but some say it's helped.

Work

Remote work, at least as we are currently able to imagine it, is a kind of double-edged sword: It can mean better work-life boundaries, or the complete erosion of them; more flexibility for parents with small children, or near-impossible conditions; more workplace harassment or less.

For a group of Black women who spoke to the Washington Post, working from home has been an indisputable good, reducing workplace microaggressions, interactions with rude coworkers, and the pressure to conform to white expectations of professionalism. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re working in isolation: During the last year-plus of the pandemic, many Black women have organized coworking pods with each other—a practice that pre-dates covid, according to the Post—creating a version of office life that better suits them.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-