The Centuries-Old Symbolism of a Woman at Her Industrious, Somewhat Sexual Spinning

In Depth

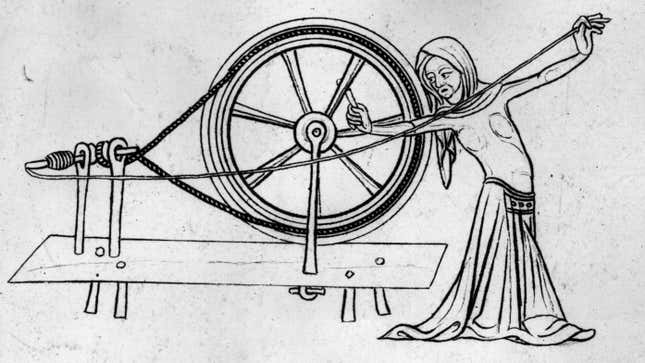

Image: (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A spindle whorl doesn’t look like much. It’s a small cone, disk, or sphere made of a hard material such as stone, clay, or wood, with a hole through the center. Museums often own thousands but display only a handful to the public. Even these special few, singled out for their decorative paint or engraving, are easily overlooked in favor of the showier vases, bowls, and statuettes nearby. “Spindle whorls are not the most spectacular objects found by archaeologists,” concedes a researcher. They are, however, among the earliest and most important human technologies—a simple machine as essential as agriculture in going from small amounts of string to the large quantities of yarn needed for making cloth.

“The spindle was the first wheel,” Elizabeth Barber tells me, gesturing to demonstrate. “It wasn’t yet load bearing, but the principle of rotation is there.” A linguist by training and weaver by avocation, Barber started noticing footnotes about textiles scattered through the archaeological literature in the 1970s. She thought she’d spend nine months pulling together what was known. Her little project turned into a decades-long exploration that helped to turn textile archaeology into a full-blown field. Textile production, Barber writes, “is older than pottery or metallurgy and perhaps even than agriculture and stock-breeding.” And textile production depends on spinning.

Leaving aside silk, which we’ll get to later, even the best plant and animal fibers are short, weak, and disorderly. Flax fibers can reach a foot or two, but six inches is as long as a strand of wool will grow. Cotton typically runs only an eighth of an inch, with the most luxurious varieties extending no more than two and a half inches. Drawing out these short fibers, known generically as staple, and twisting them together—spinning, in other words—produces strong yarn, as individual fibers wind together in a helix, creating friction as they rub against each other. “The harder you pull length wise, the harder the fibers press against each other crosswise,” explains a biomechanics researcher. Spinning also extends the length of staple fibers, producing thread that can stretch for miles if needed—as it usually is.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-