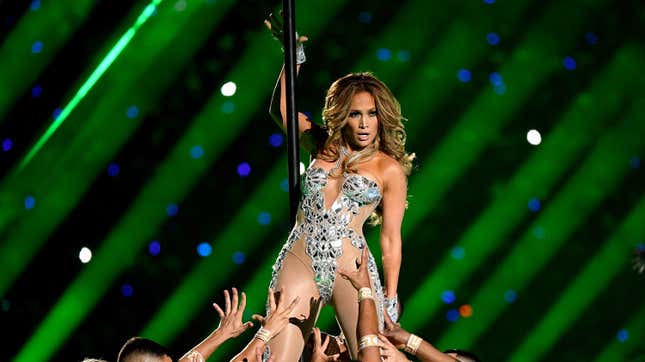

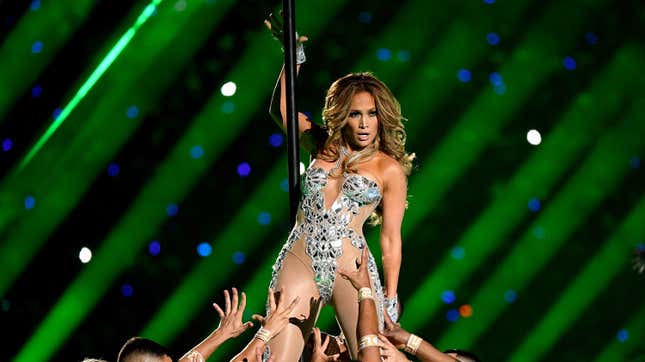

The J.Lo Super Bowl Discourse Is All About the Invisibility of Middle-Aged Women

Latest

Today we learned that in the wake of the Super Bowl halftime show, novelist Jennifer Weiner and many of her “middle-age mom” Facebook friends felt personally implicated by 50-year-old Jennifer Lopez’s physique—or, to put it in Weiner’s words, “judged by dat ass.” In a New York Times opinion piece, Weiner waxes in disbelief that “at 50, [Lopez] is a force of nature, a woman who looks so amazing it’s like evolution took a tiny step forward, just for her.” Some of Weiner’s Facebook friends were “in awe” at this alleged evolutionary masterpiece, while others, like herself, also felt the pull of unfavorable personal comparisons.

Weiner’s piece is representative of the jaw-dropped reactions on social media to Lopez’s halftime performance, which are but a variation on the responses last year to her pole-dancing scenes in Hustlers, and both are direct products of middle-aged women’s sexual invisibility. In that halftime show, as with her existence on any stage or screen, J. Lo demonstrates the possibility of being a 50-year-old sex symbol, an older woman on display. There is cognitive dissonance here, because women of her age are so infrequently seen in this way: sexy, vivacious, and worthy of the camera’s zoomed-in gaze.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-