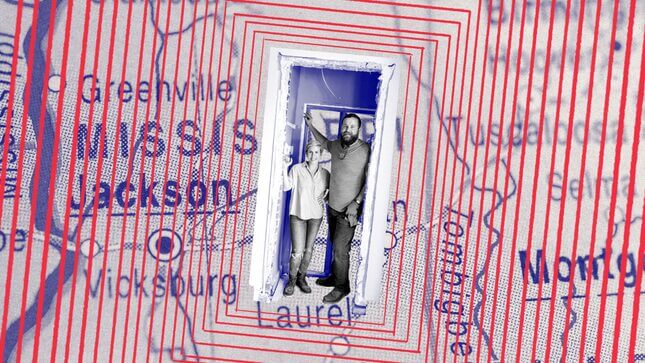

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: HGTV, Shutterstock)

In a 2019 episode of HGTV’s juggernaut show Home Town, husband and wife Ben and Erin Napier stand in the kitchen of a dilapidated Craftsman cottage, urging their clients to see their vision for the Wallace House, a pink cottage with rotting floorboards that has good bones and a lot of hidden potential. The kitchen is a mess, but there is one saving grace: a breakfast nook that could turn into a “cozy book nook.” Erin Napier lays out her vision for the book nook, one surrounded by built-in shelves and an armchair. This personal touch, which would sway any homebuyer enough to put their faith in the Napiers’ capable hands, is enough for the couple to commit. The clients, a young lesbian couple with roots in Laurel, Mississippi, where Home Town is set, buy the Wallace House for a pittance.

At the end of the episode, the house is exactly as the Napiers described and the book nook is everything they promised. The clients thrilled with their new home: a shiny new jewel in Laurel’s crown. Ben and Erin beam, obviously pleased that another dilapidated house has been lovingly restored for a couple who, like the Napiers, are invested in Laurel’s rehabilitation. Erin is from Laurel, and willingly moved back to her hometown after college, drawn to the place that made her. In contrast, Ben is a preacher’s kid with no discernible hometown, who has adopted Laurel as his own. Together they’re transforming the small Mississippi town into a modern-day Mayberry, selling their anesthetized brand of Southern charm to the widest audience possible.

In a true harbinger of the kind of fame that awaits them, the Napiers landed the cover of the April 2020 People Magazine. Erin, a sunny blonde with a pixie cut, gazes into the camera lens with a beatific smile as she leans against her husband Ben, a big, solid hunk of a man resplendent in plaid and a tidy red beard. “Small-town sweethearts to superstars,” coos the copy, promising a storybook romance and small-town values wrapped up in a tidy, family-focused package. When predecessors Chip and Joanna Gaines left HGTV in 2018 after four successful seasons, it created an opening for a similar dynamic. The Napiers quickly stepped in to take their place as America’s first family of home renovation and tradition. Home Town is sunny, effervescence laser-focused on the fantasy of putting down roots in a small town where houses are cheap and a dream home is accessible played to HGTV’s core audience. The Season 4 premiere, in January 2020, was the highest-rated premiere for the series since its debut in 2017.

On Home Town, it’s not just about houses, it’s about history. Each house is presented to the clients with a backstory about its previous owners and the proposed renovations always try to preserve or replicate a specific feel. The history that they provide about the houses is mostly superficial, but folksy enough to feel quaint. This history, which is never verified, is part of the home’s allure. In the world of Home Town, budgets are limited and the Napiers work to keep or rehabilitate as much as they can. They never do the full gut renovation like the Gaineses did, but are focused on realistic renovations for middle-class homebuyers. The result is cozy but still luxurious, a house that is both lovely to look at but also livable: In other words, it feels like home.

HGTV’s producers have positioned the Napiers as the saviors of Laurel. The introduction to the show has changed by season, evolving as the show’s mission becomes clear. By Season 4, the introduction to the show cements their position thusly: “If we keep going the way we’re going, in ten years, everything will be shined up and completely new,” Erin chirps. Viewed once, this reads as a folksy sentiment, but after three episodes in a row, it begins to feel a little menacing.

Laurel is a textbook example of the nostalgia often elicited by small towns. The Napiers want the denizens of Laurel to commit to their vision of community: a largely homogenous, folksy small-town vibe that neatly obscures the realities of the place itself. Home Town operates on one hand as a standard home renovation show resulting in showstopper houses lovingly restored to a bright and shiny version of their past selves. On the other, it is a powerful marketing campaign for the importance of growing roots in American small towns.

Home Town hews to the same format as Fixer Upper and other marquee offerings, but there are a few key differences that set it apart. Unlike Chip and Joanna Gaines, who now helm a lifestyle empire that includes a home goods line at Target and their own network, the Napiers are still niche enough to pull off aw-shucks humility. Both the Napiers and the Gaineses serve as unofficial ambassadors for the towns they’ve chosen to revitalize, but their ambassadorship manifests in different ways. The Napiers have yet to open a giant complex in Laurel that pushes their personal brand, but they do have Laurel Mercantile, a small storefront in Laurel’s downtown, selling antique quilts and handcrafted wood furniture and “gentleman’s workwear” from Scotsman Co., Ben’s woodshop and furniture company. And while a full-bore takeover of Laurel isn’t quite in the cards yet, Erin and Ben hint at what their future might hold.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-