The Poetry Foundation Makes Good on Its Commitment to Diversity by Publishing a Convicted Sex Offender

In Depth

In the literary world, Poetry magazine, published by the almost staggeringly wealthy (by literary world standards) Poetry Foundation, is considered the publication of record for the industry. Its struggles to include voices not belonging to white people, specifically those not belonging to white men, have also been well-documented. Most recently last summer, when 1,800 people called out Poetry and the Poetry Foundation for its tone-deaf and superficial commitment to “engaging in this work to eradicate institutional racism” as a response to the police murders of Black people and nationwide protests against the ongoing violence. Perhaps as a misguided attempt to make good on whatever that promise was, Poetry dedicated its February issue to elevating the voices of the incarcerated, among them a white male professor and sex offender who recently served time for possessing, receiving, and distributing child pornography.

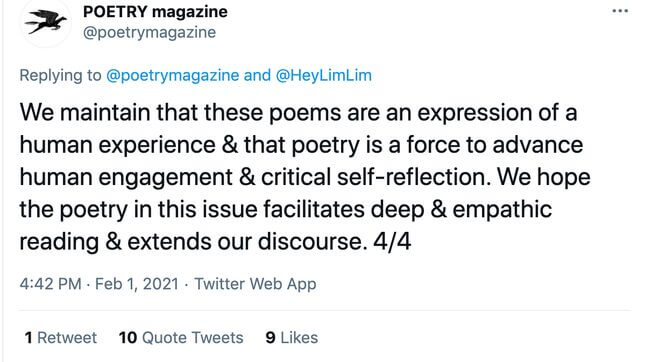

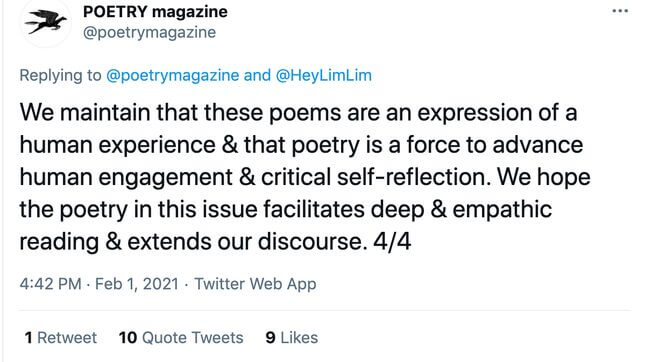

In 2015, Kirk Nesset, a former literature professor at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, pled guilty to storing “half a million images of child pornography, child erotica and child modeling on his computer” following an FBI and state police investigation, resulting in a six-year and four-month sentence. He was released in September and now can boast a byline in one of the biggest poetry publications in the world—one that accepts just 12 percent of the poems submitted by hopeful writers the world over—not in spite of but because of the fact that he stored hundreds of thousands of images depicting child torture and got caught. Understandably, subscribers to the magazine as well as people interested in de-platforming pedophiles were unhappy with the decision. Nearly as baffling, Poetry decided to issue a statement on the matter with a four-message reply to a tweet from an account with less than 200 followers:

“People in prison have been sentenced & are serving/have served those sentences; it is not our role to further judge or punish them as a result of their criminal convictions. As editors, our role is to read poems & facilitate conversations around contemporary poetry,” lectured one message.

Whoever was posting on behalf of Poetry went on to explain that editors did not know that the poet was a convicted sex offender in the interest of fairness or something:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-