The Slice of Internet Where Cancer Patients Control Their Lives & Share Their Joy

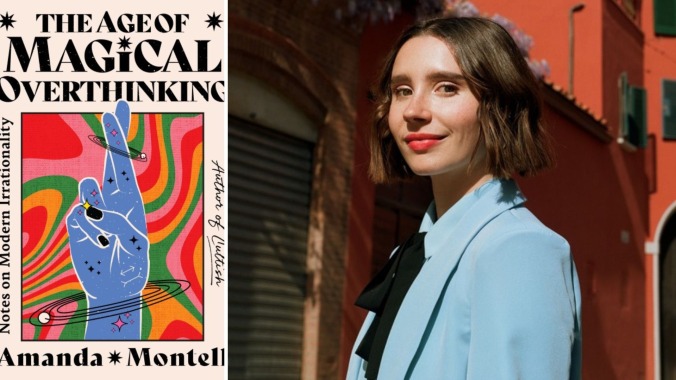

But "survivorship bias" often sneaks into how viewers perceive these stories, as Amanda Montell writes in her new book, The Age of Magical Overthinking.

Photostock BooksEntertainment

In her new book, The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern Irrationality, Amanda Montell embarks on a journey to explain the cognitive biases that warp our very-online brains. From attributing the appeal of conspiratorial wellness influencers to proportionality bias to debunking the “zero sum bias” that prompts the debilitating comparisons we make on social media, Montell puts words (and real psychological concepts) to some of the most persistent angsts of the 2020s. In the excerpt below, from her chapter “What It’s Like To Die Online,” Montell writes about cancer YouTubers who share their experiences—from diagnosis to, sometimes, death—and how documenting the randomness of life’s crappiness challenges society’s survivorship bias.

Of the six dying girls I interviewed, only one besides Racheli survived. Her name was Mary. She was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a childhood bone cancer, at age 15. I still keep up with Mary on Instagram, and it’s by far my most positive use of the app. My heart climbs to my throat every time I see her reach any life milestone, big or small: high school graduation, college acceptance, a new hair color. Her hair came back like an avalanche. When I interviewed Mary in 2017, she had recently finished her last of 14 chemo rounds. Fuzz had begun returning to her scalp in tawny patches, like continents on a milky globe. Mary was still a minor when she went through treatment, so the decisions about her health weren’t entirely up to her. Filming and editing YouTube videos—“A Week with a Cancer Patient | hospital vlog,” “Best & Worst Parts of Having Cancer”—became a pleasurable way of gaining some agency. And the sense of routine helped pass those long, boring hospital stays. “When I got sick I was really lonely and didn’t have a lot of ways to reach out to people,” Mary explained. “YouTube was therapeutic. Even though there were so many terrible things happening, I could make the terrible things into a video, into art. I could share it with people in my own way. That helped me cope.” Almost every day, viewers left comments that Mary’s videos put their problems into perspective: breakups, bad report cards.

The dying girls’ “imperfect” vlogs made use of YouTube as a virtual gallery space, challenging survivorship bias like physical art never could. Their raw, self-authored sketches of day-to-day illness were digital artifacts—a collection of amateur pottery and fabric that can’t disintegrate with age.

These young women’s videos also questioned the fantasy portrayals of cancer preferred by the news, which only inflame viewers’ survivorship bias. “Inspiration porn” defines a whole media genre where folks with severe health impairments are depicted trouncing obstacles with sheer will. Most Americans with disabilities are not sufficiently employed or supported, no matter how resolute they are. A 2015 study published in the Disability and Health Journal concluded that individuals with physical disabilities are 75 percent less likely to have their medical needs met than their able-bodied peers. “People with disabilities have largely been unrecognized as a population for public health attention,” concluded another 2015 study from the American Journal of Public Health. The findings showed that adults with congenital defects, late-onset illness, or injuries were almost three times as likely to be unemployed and more than twice as likely to have a household income of less than $15,000. Most terminal cancer patients don’t make “miraculous” recoveries thanks to their swell attitudes. Most dying girls don’t become YouTube famous.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-