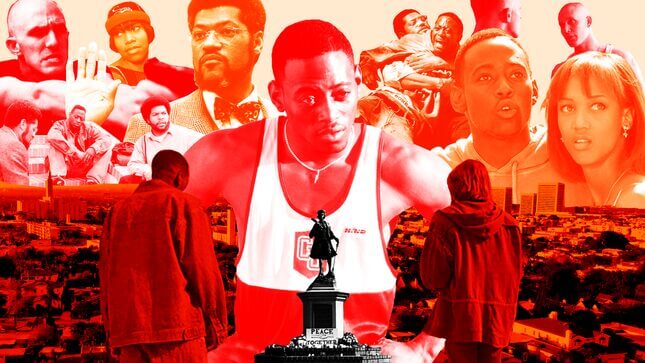

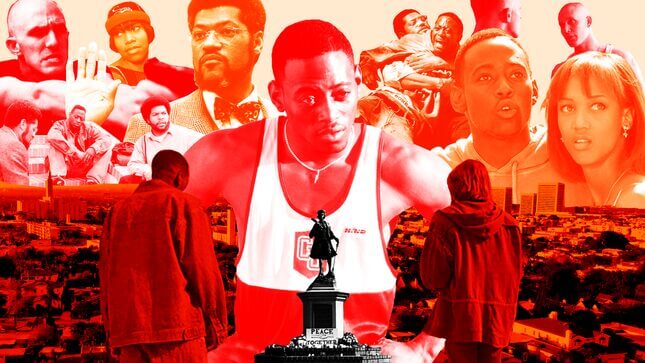

Two Decades After Higher Learning, the Black Experience at White Colleges Remains Fractured

EntertainmentMovies

Most people remember John Singleton from his 1991 film Boyz n the Hood, an unforgettably striking debut from a filmmaker who knew how to straddle empathy and tension. The film became both a foundation and defining facet of Singleton’s legacy almost to the exclusion of all else, doing what Illmatic did for Nas’s career; everything which came after would always be compared to that incredible first.

Yet Singleton, who died in April 2019, entered into Hollywood and left it doing something he was so unnervingly skilled at; the action of place-making. In Rosewood he captured the shift from balmy serenity to palpable horror and in Shaft, the inescapable, brightly-lit streets of New York were a character of their own in a retelling of white violence and corrupt justice. Singleton had an intuitive understanding of the politics and fragility of placemaking, and when he looked at his city of Los Angeles (which he did often), he steadily transported viewers through the communities he understood as central to questions on belonging and displacement. This is most apparent and memorable in 1995’s Higher Learning, his foray into the experiences of Black students who found themselves at a predominantly white institution where they tried to both find their place and simultaneously stand apart from an environment that refused to see them.

For the most part, anyone who went to a PWI will understand the need to find or create spaces with people who understand your reality, not simply as a student maneuvering through the bureaucracy of higher education, but a Black person moving through institutions historically built to exclude them. This exclusion is embedded into the DNA of higher education from institution names and enrollment policies to curriculums and the treatment of faculty. While in university, I remember a popular Criminology and Sociology professor whose dreadlocks and nonchalant, minding-my-own-business demeanor always had students asking him if he could spare a joint. After a while it became something humorous, even though the covert violence behind that question was unmistakably clear. That this person was in a position of power was seemingly impossible for them to fathom.

Throughout the years, a number of television shows have sought to mirror Black student life at PWIs, with Dear White People being the most recent iteration. It’s hard to imagine that Higher Learning did not influence the Netflix show, whose characters though they deliver more tongue-in-cheek wittiness on racial power dynamics, owe a hat tilt to the place-making legacy of Singleton.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-