Woman Discovers Her Photos Have Been Used to Catfish Others for Years

Latest

Most of our discussions of catfishing are limited to the catfishers and catfishees, but there’s a third category we often forget about: the unwitting catfish-complicit, whose pictures and deets make the catfishing possible, and whose lives also get crappy and complicated when sucked into the mix.

For one startling example, take Ellie Flynn in the U.K., who has dealt with distress, creepiness and in-person mix-ups resulting from having her pictures and those of her many friends cribbed from her social media accounts for years by a woman who appears to be in her social network. Maybe someone she went to school with. Possibly an actual, real-life friend.

Flynn writes for Vice:

Over the years, my friends and I have met a number of young men who’ve spent a substantial amount of time chatting to fake me—or fake versions of one of my friends—online. They often demand we show some form of ID to prove our surnames aren’t “Colarossi,” or “Rose,” or “Morrison,” and each time they’re left disappointed. The boy from Malia had been speaking to “Chia” every night on the phone for two months. He believed he was in love with her. I couldn’t help but feel for him—though I did find it odd his suspicions hadn’t been raised by the fact this cyber charlatan apparently had a family emergency to attend to literally every time they were due to meet.

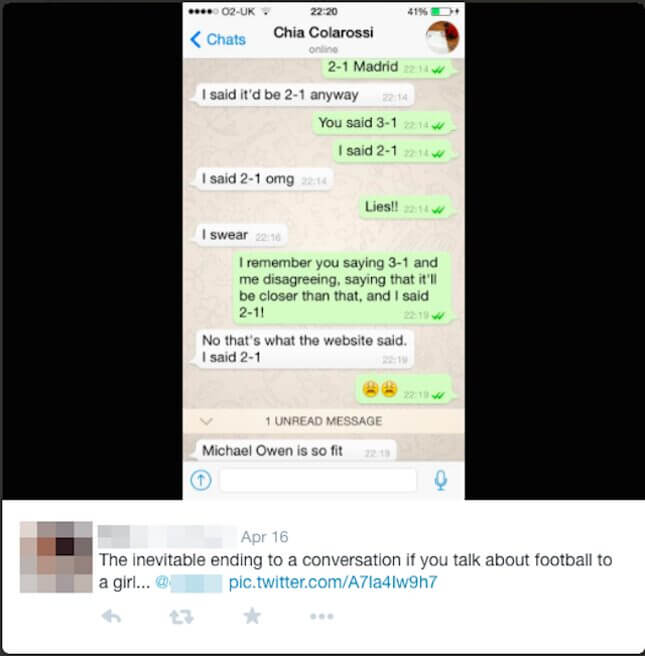

One such man provided proof of the fake excuses:

In total, Flynn says there are over 60 fake profiles floating around out there on every social media site imaginable—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and dating sites—impersonating her and her friends. The impersonators are following her closely:

Every photo we upload is re-posted to Facebook by our respective fake accounts; every job we start is updated on our profiles; every tweet is repeated. It’s so believable that I’ve genuinely considered whether or not there’s a parallel group of everyone I know (with slightly different second names) living somewhere in Halifax.

Worse, the eager Romeos being fished with these photos and updates and re-Tweeted witticisms are sometimes showing up to where the real Ellie and Chia live or hang, which indicates further that the person scraping their site for the fake profiles is a “friend,” at least in the social media sense, and has access to all pertinent status updates: the real Chia was recently approached in her college dorm.

Flynn speculates that perhaps it’s the fake Chia who is the main instigator for all the meet-ups, since it’s her fake profile that gets the most tending, and the most activity:

Fake Chia has tweeted 36,000 times. Let me put that into perspective—that’s a tweet an hour for more than four years. Using some sort of bizarre reverse psychology, fake Chia sometimes even messages real Chia asking, “Why are you pretending to be me?”

The whole situation is utter fucking madness, and really, really confusing.

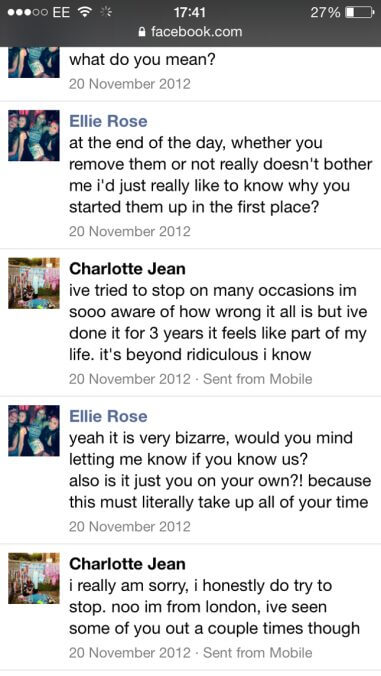

Real Ellie and her friends have tried to squash the charade. They’ve asked Facebook and Twitter to take down the accounts due to fraud, and they’ve succeeded in some cases, but the fakes always reappear in a matter of weeks. They’ve even messaged the fake profiles to try to get whoever’s behind this to stop:

In an act of desperation a few years ago, I messaged the fake Facebook account of my friend Charlotte, asking why the profiles had been set up, and explaining that I was becoming concerned about the very creepy scenario we’d found ourselves in.

This is the response I received (confusingly, I’d changed my name to “Ellie Rose” on Facebook at the time, but ignore that):

“Charlotte Jean” later told me: “I don’t have very many friends at all—I never have had, to be honest. It sounds absurd, but it just makes me feel a little bit better about myself. Nobody talks to me when I’m being myself.”

She swore to real Ellie that she would cut out the nonsense, but the pranks continued:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-