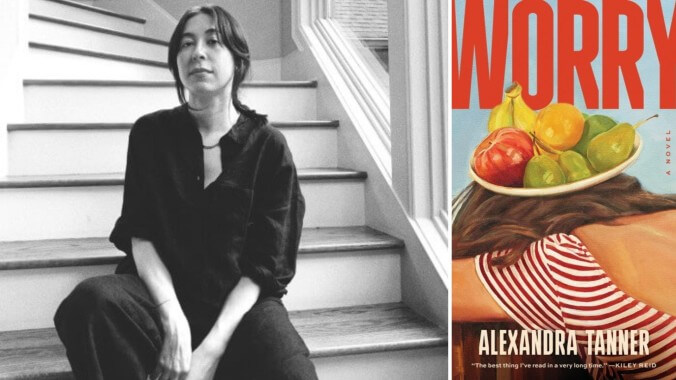

A Debut Novel Obsesses Over Tradwife Mommy Bloggers and Toxic Mothers

In Worry, Alexandra Tanner tells a disturbingly relatable tale of the destructive, wasteful ways we become addicted to content we don’t even like.

Photo: Shutterstock BooksEntertainment

Chief among the perils and delights of the internet is the ability it has given us to peer into the lives of those others, whether we know them or not. Sometimes that means checking up on an old nemesis; other times it’s noting the sudden absence of a former partner; still others it’s fixating on a celebrity. For Alexandra Tanner, it took the form of obsessing over an Instagram ensemble of Mormon moms, evangelicals, fundamentalists, homesteaders, and anyone calling themselves something that begins with “trad”—women who believe fluoride in tap water will kill you, while camel milk and essential oils can stave off early death. She documented her fevered stalking in a 2020 essay in Jewish Currents titled, deliciously, “My Mommies and Me.”

Now, in her debut novel Worry, Tanner has returned to this obsession in the form of her protagonist, Jules, who collects these women “like Beanie Babies,” absorbing their posts of “the sickest, most deranged content imaginable.” Jules justifies this compulsion in a pithy meta-gesture by Tanner: “I’m studying them… for this essay I’m writing… about America, and Jews, and assimilation, and militancy, and God, and conspiracism, and whatever.” (The essay never materializes.) She admits it activates something malevolent in her—“the part of my brain that loves hateful things is aglow”—and, in this way, Worry tells a disturbingly relatable tale of the destructive, wasteful ways we become addicted to content we don’t even like.

For most of the book, Jules and her younger sister, Poppy, hang out in their shared Brooklyn apartment, fawning over their dog or bickering. Worry is, in many ways, a character study of sisterhood—its endless cycle of fondness and frustration and guilt—and favors behavioral scrutiny over plot. The threads of obsession in the book intersect at regular intervals with Jules’ and Poppy’s job woes (at an astrology startup and an academic publisher, respectively), youthful immorality, and familial dysfunction.

We spoke to Tanner while she was visiting her own family in Florida, discussing doom-scrolling, Girls, and Thanksgiving, as her dog occasionally chimed in from the next room. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

In 2020, you wrote an essay called “My Mommies and Me.” How was writing about these mommy bloggers in an essay form different than doing so in your novel?

I started following a bunch of mommy bloggers in late 2019, early 2020. I had started working on Worry already, and I knew that I wanted the internet to be a big part of it. As my obsession with the mommies deepened, I made the focus of Jules’ internet habits the mommy bloggers, rather than just random people on Instagram.

Both in the essay and in the novel, there’s a grappling with this idea of “what does it mean to spend time with these people?” At one point, Jules says, “Things aren’t so bad in my life, I think. At least, I’m not one of these people or one of their followers. Then I realize that I am, of course, one of their followers, a devoted one, even, in my own fucked up little way.” She’s following them critically, but they still take up all her time.

Well, that’s the thing, right? In real life, the habits you form throughout your days add up to who you are and what your life looks like. When I’m doom-scrolling on the internet, I don’t think of it as being a significant part of who I am. But over time—especially when you have one niche obsession, like the mommies—it really does become a huge part of your consciousness and your preoccupations and it changes who you are a little bit. I’m certainly not a responsible Internet user. Everyone else has rookie screentime numbers to me. But we have to do something about that at some point: looking at the sum of what spending your time in that way does to you, and accepting that you are one of these people’s followers. You are in some way feeding them, even if you tell yourself you’re better than them or you’re separate from them or it’s just a little guilty pleasure you have.

There’s a lot of humor in this obsessiveness: The mommies are absurdist unto themselves, but also the way you frame it, and the way Jules is framing them, is funny. How do you keep this aspect light when what these women say actually makes you want to, like, weep?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-