Notorious 1970s Serial Killer Reduced to Nose-Picking Incel in New Novel

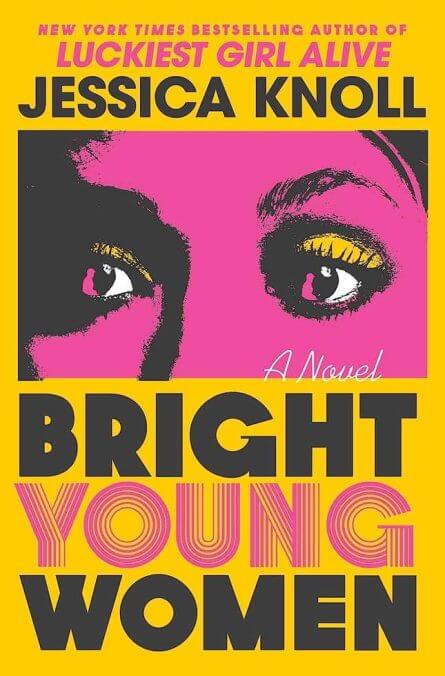

“I think any woman who was approached by him was like, something’s off with this guy,” Jessica Knoll told Jezebel of her inspiration for Bright Young Women.

BooksEntertainment

Jessica Knoll’s third novel, Bright Young Women, isn’t just a story based on Ted Bundy’s string of horrific murders…it rewrites the entire narrative around the notorious 1970s serial killer. Specifically, Bright Young Women is told through the eyes of Bundy’s victims—a perspective that’s been effectively ignored, beginning when one newspaper in 1978 described him as “Kennedy-esque” and persisting up until one streaming platform in 2019 cast Zac Efron to play him. The book is 376 pages, and Knoll doesn’t write the words “Ted Bundy” one single time.

“Once I started researching him and his crimes, I realized we’d gotten the story wrong,” Knoll told Jezebel. “I think any woman in her right mind who was approached by him was like, something’s off with this guy.”

But since we know so little about Bundy’s dozens of victims, Knoll invented their worlds herself. The timelines and causes of death are all true, but Knoll’s main characters—Pamela, Denise, Tina, and Ruth—are (mostly) not. Denise is murdered in a sorority house at Florida State University at the beginning of the novel (set in 1978). Her best friend Pamela is the only eyewitness, which quickly attracts Tina—a rich widow whose own best friend, 20-something Ruth, went missing years before. Through them, we learn tons of little side facts about the time period, all seemingly meant to punctuate the bullshit of Bundy’s real-life victims being all but erased from their own stories. For example, we learn the story of Frank Tucker, the district attorney in Aspen, Colorado, who was partly to blame for one of Bundy’s escapes…and who was later charged with embezzlement of public funds that he used to pay for his mistress’s abortion. Or, my personal favorite, the story behind 19th-century wearing blankets made by Navajo women.

That story found its way into the book through Denise, a lively and dedicated art history major who had a job lined up with Salvador Dalí after graduation—and a piece of a Navajo wearing blanket hanging about her bed. That detail is eventually revealed by Pamela, the type-A sorority president who’s convinced herself she wants to attend a small law school in Florida that her boyfriend got into, instead of Columbia Law, which only she got into. Pamela spends the novel oscillating between the past and the present, working to ensure the killer’s conviction and revealing pieces of Denise’s life throughout:

I thought about that weaving hanging about Denise’s bedroom wall in Jacksonville…It was a scrap from a Navajo wearing blanket and you could tell that the woman who made it did so under duress, Denise once explained to me. See the radio patterns of the lines? She’d pointed them out, rising and falling hard horizontally, creating a chaotic diamond series. The shapes only started to appear in the mid-nineteenth century, when Hispanic families in the southwest captured and enslaved Navajo women and children. The textiles were valuables and the women were forced to create them for their captive family’s profit. In a show of defiance, they invented a new loom sequencing meant to communicate that these weavings were not made by choice.

But in a book that reduces Bundy to a “run-of-the-mill incel whom I caught picking his nose in the courtroom. More than once,” it’s impossible to choose just one historical anecdote to highlight. With every turn of the page, there’s a snarky exchange, enraged revelation about how society treats women, or biting takedown of the idiot men who always seem to have all the power. Knoll sat down with Jezebel to talk about unresolved grief, watching morbid things, and the bumbling policing that let Bundy get away. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JEZEBEL: This was a triumph. You rewrote history.

Jessica Knoll: My job here is done.

One thing that stuck out to me was how you had Pamela tell all these little anecdotes, side stories almost, of the Navajo women and Tucker the Fucker. Did you already have those stories in mind?

It just is the byproduct of living with this story for as long as I did and how challenging it was, personally, for me to write. It did feel like such a big undertaking. This is a story that’s been already enshrined in history, so if I’m going to add my voice to the mix, I better have something different to say. Because obviously this story’s been told so many times, but always from the same perspective.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-