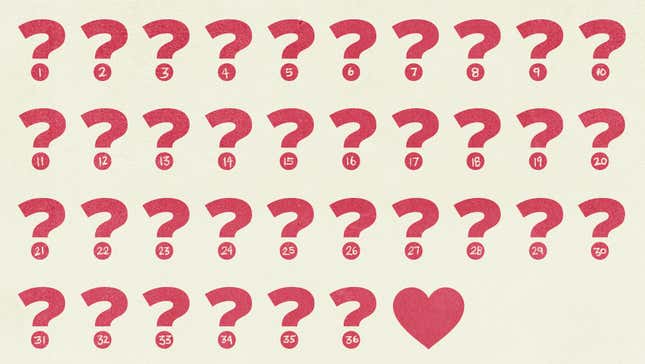

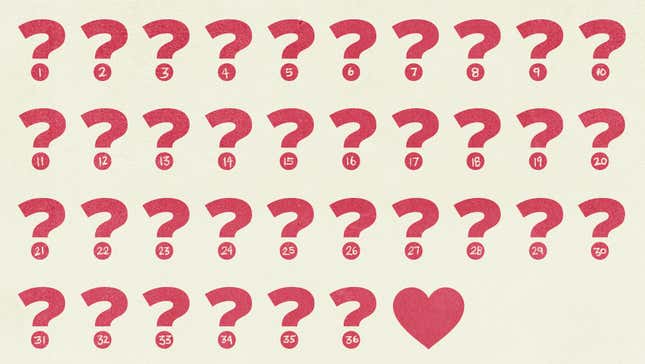

Here Are the 36 Questions That Will Allegedly Make You Fall in Love

Latest

If you didn’t read the wildly popular Modern Love column this weekend about how easy it is to fall in love if you and your chosen one just spend a few hours answering these 36 questions, then I guess you’re just not an actual human with a beating heart.

It’s a fascinating read. In it, author and academic Mandy Len Catron recounts how she applied psychologist Arthur Aron’s decades-old study—wherein he made two participants fall in love in a lab with a series of increasingly intimate questions—to her own love life. She tried it with a “university acquaintance,” a man she’d taken notice of but didn’t yet really know. Catron writes:

I explained the study to my university acquaintance. A heterosexual man and woman enter the lab through separate doors. They sit face to face and answer a series of increasingly personal questions. Then they stare silently into each other’s eyes for four minutes. The most tantalizing detail: Six months later, two participants were married. They invited the entire lab to the ceremony.

“Let’s try it,” he said.

It’s nerdy, it’s romantic, and I like it. So did Catron and her colleague. They hit up a bar, Googled the questions, and what followed is the sort of back and forth you usually build up to, conversation-wise, over weeks, or months, or even years with a new someone—except there it was, intellectual courtship on speed.

It wasn’t a perfect setup, Catron notes:

First, we were in a bar, not a lab. Second, we weren’t strangers. Not only that, but I see now that one neither suggests nor agrees to try an experiment designed to create romantic love if one isn’t open to this happening.

This is a really key concept here—whether you agree with it or not. In the universe where you do agree, you believe that in order to fall in love you must be open to the possibility of love. This likely means a pre-existing attraction and interest, or at least a lack of red flags, or the hesitation that might come along with, say, being really attracted to someone you can already tell is bad for you.

But anyway, those questions, which are in full here. Catron writes:

They began innocuously: “Would you like to be famous? In what way?” And “When did you last sing to yourself? To someone else?”

But they quickly became probing.

In response to the prompt, “Name three things you and your partner appear to have in common,” he looked at me and said, “I think we’re both interested in each other.”

I grinned and gulped my beer as he listed two more commonalities I then promptly forgot. We exchanged stories about the last time we each cried, and confessed the one thing we’d like to ask a fortuneteller. We explained our relationships with our mothers.

Because the vulnerability increased gradually, Catron says, it wasn’t as awkward as diving in immediately to third-base intimacy. Instead, she was scarcely aware they’d become closer until in retrospect when they took a quick bathroom break, and then later, as the weeks wore on.

More interesting perhaps is Catron’s observation that the questions may work in such short time because they disrupt the way we normally get to know people—which is typically by telling our story, one full of highs and lows, serious insights and funny asides that we’ve each been honing for years—decades even—and must unravel for a new person every time we decide to give it a try again.

These questions, taken together, mix it all up and act as a kind of shorthand version of the same thing—a more direct route to things your “story” actually reveals about you over time, like what you really value, how you see yourself, what you see your strengths and shortcomings as, how you relate to others and the world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-