Hollywood Has A Colorism Problem, And The Conversation Keeps Going Nowhere

After the latest casting outrage, why aren't more people in the entertainment industry talking about this?

EntertainmentMovies

Last week, a trailer for Netflix’s upcoming Western The Harder They Fall dropped— a film Indiewire described as “the biggest, poppiest, and most star-studded Black Western ever made.” It has a stellar all-Black leading cast that includes Idris Elba, Regina Hall, Lakeith Stanfield and Jonathan Majors. The film looks, on its surface, pretty good—a refreshing take on a genre that’s heavily dominated by and associated with whiteness. It ticks many of the arbitrary diversity boxes that some people rely on to decide whether a movie is doing “representation” right: a predominantly Black cast, Black producers, a Black writer-director.

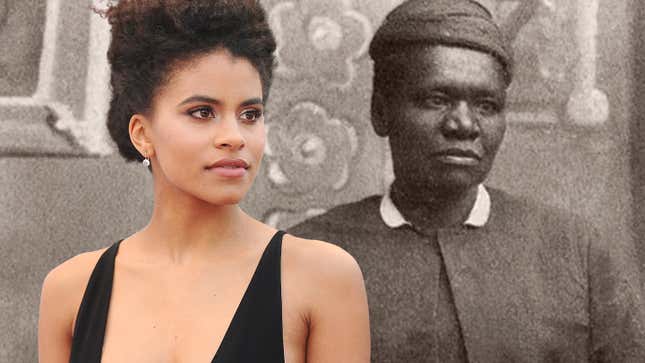

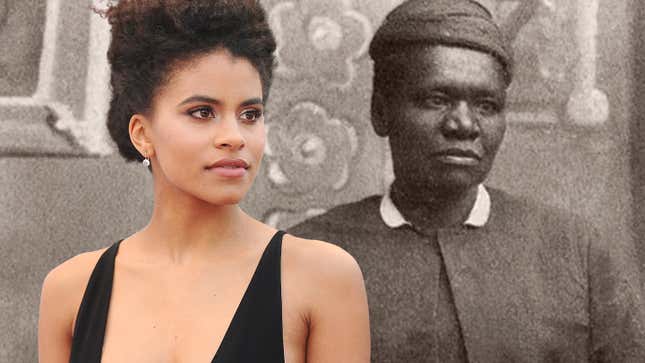

And yet, the casting of one of the movie’s stars, Zazie Beetz, has rightfully raised some eyebrows. The character Beetz plays, Stagecoach Mary, is based on a real person: a dark-skinned Black woman who, after being emancipated from slavery, became a mail carrier infamous for “liking liquor and gunfights.” The question is why a light-skinned actor like Beetz was chosen for a role traditionally played by darker-skinned actors like Esther Rolle, Dawnn Lewis, and Kimberly Elise.

Do people in Hollywood know colorism is a thing? That it is, in fact, the thing people should be talking about when they talk about racial inclusion, particularly for Black people? Race is a construct, yes, but it’s also true that that construct is based almost entirely on skin tone, hair texture, and features. The thing about colorism—the trick of it, really—is that it is the water in which all Black people swim, but only the people who are directly affected by it seem concerned with talking about it. This is by design: Colorism and racism are essentially different sides of the same coin.

The colorism conversation, especially as it pertains to Black women, often revolves around desirability. And while the association of light-skinned blackness with romantic desirability is certainly a problem, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. The reality is that colorism and featurism are deciding factors in every facet of life. And if the conversation were to move past desirability, certain other truths about colorism would have to be acknowledged.

Research shows that dark-skinned Black girls are three times as likely to be suspended from school than light-skinned Black girls. Dark-skinned Black women earn up to 25 percent less money than lighter-skinned women across the world. Dark-skinned Black women are more likely to receive longer and harsher prison sentences; they are more likely to be perceived as dangerous, or aggressive. They are more likely to be victims of police brutality and intimate partner violence. And so on, and so on.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-