Inside the Caliphate Debacle, and Exactly Who Is Allowed to Fail

Latest

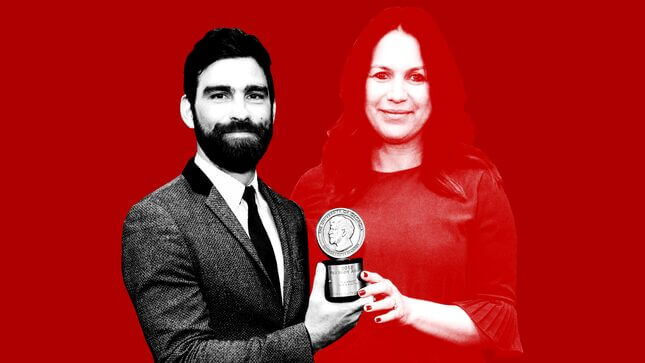

Graphic: Elena Scotti

One morning in late December, the documentarian and producer Kelsey Padgett turned on the New York Times’ The Daily, a podcast she listens to nearly every day. It had been less than a week since the Times had retracted-but-not-quite-retracted its award-winning Caliphate podcast, following an investigation into a deceptive source, and Padgett was stunned, she says, to hear one of the show’s most visible producers, her former colleague Andy Mills, hosting “a fun story” that day.

“My wife was enraged,” says Padgett. “She said, ‘He’s going to get away with it again.”

Nearly three years earlier, Padgett had been a source for a New York Magazine story about how WNYC was handling accusations of bullying and misogyny, some of it involving Mills. As the story reported, an H.R. investigation into the producer’s behavior was marked resolved with little fanfare, after he signed a statement of reprimand and performed an hour of behavioral training. The long-term consequences of what former colleagues and acquaintances have described as a pattern of sexism and workplace misconduct were muted. Mills apologized in print and moved on to the Times—where his female boss vouched for his ability to work “with and for women inside an audio department that is predominantly female”—and came to work on the paper’s flagship investigative podcast, where his career thrived. When the project exploded spectacularly in late 2020, Mills—who had originally pitched the podcast and appeared regularly on the show—emerged relatively unscathed, while the reporter Rukmini Callimachi publicly apologized and was reassigned from her beat.

“Him not being accountable in any way for the failures of Caliphate while his female reporting counterpart takes all the public scrutiny says a lot,” says Padgett.

Shortly after hearing the Daily episode, Padgett became one of the first women in audio to tweet about Mills’s behavior in the workplace and at industry events. This behavior, allegedly ranging from publicly disparaging female colleagues to making unwelcome advances, was apparently well known in a segment of the industry and discussed quietly for years, but hadn’t impacted his trajectory much at all. But as Mills’s former colleagues began publicly airing pointed complaints, the sudden exposure of the whisper network reverberated.

On January 7th, Mills’s former employer, Radiolab, posted an apology on its website, citing “conversations about tolerance of bad behavior in our industry and in particular a person who worked on our show five years ago, Andy Mills.” A week later, as NPR reported, a coalition of 20 influential public radio stations sent a letter calling Daily host Michael Barbaro’s “credibility into question,” criticizing his fumbling of the Caliphate retraction and, among other things, raising questions about Mills’s continued prominence at the operation. The Washington Post’s media columnist reports these “concerns” have reached “the upper levels of the Times,” according to one unnamed source. Over the last month, at least four public stations have dropped Barbaro’s show in protest. Publicly, the paper has remained politely contrite.

The Times’ choice not to equally discipline Mills is part of a broader narrative about cronyism and the somewhat complicated circumstances under which journalists atone for shoddy work. Since the Times apologized for featuring a fabulist as a central character in its podcast, Barbaro’s behavior has come under particular scrutiny. But for the women who tweeted about Mills and engaged in the agonizing private conversations about their industry that followed, this singular incident mirrors a broader unwillingness to challenge behavior that might not appear egregious to some male managers but still pushed women out of the field and left those that remained to experience “death by a thousand cuts.”

Karen Duffin, a longtime industry fixture and the current co-host of NPR’s Planet Money, has seen this dynamic replicated for years. She refers to the Caliphate situation as “a bubble that was waiting to burst.” But there’s a pressing question for her field at large, she says, about whose behavior goes unchecked. “What is it in the management process that allows them to say: We can’t let this guy go, but we can let all of these women suffer?” she asks. It’s a case study with implications beyond Mills and the Times: Years after powerful men toppled and subtler brands of misconduct explored, questions remain about who is insulated from failure and who is primed to succeed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-