Just weeks ago, the argument to defund or abolish the police was rarely heard within the mainstream. As a result of the uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, however, it is now commonplace and, in fact, being taken seriously by public servants—on Sunday, nine members of the Minneapolis City Council announced their intent to defund and dismantle the city’s police department. While the words “defund the police” may seem radical to the uninitiated (Spike Lee has warned against using that exact verbiage while supporting the cause), the rationale behind the concept is sensible. Police have frequently been called on to perform work for which they have no real training—work that can be performed by social workers, for example. Flowing the funds into social services is a preemptive, proactive way to deal with issues before they can manifest as problems.

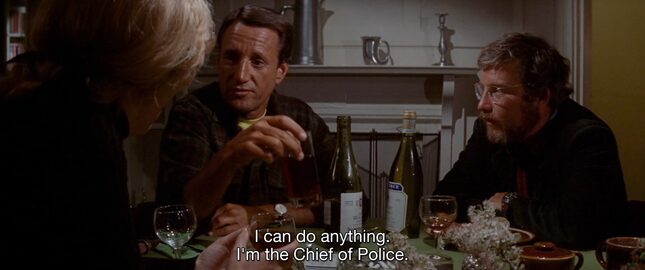

Against this social backdrop, the absurdity of the 45-year-old mother of all summer blockbusters, Jaws, has never been clearer. It is the story of a cop, with no background in marine biology and, in fact, hatred of water, taking it upon himself to hunt a great white shark, a vulnerable apex predator whose survival is crucial to the maintenance of our global ecology. At the time of Jaws’s release in 1975, your average moviegoer could have easily taken for granted the good-evil dynamic and accepted it at face value. Of course, given cinema’s tendency to frame cops as good and the police’s overall authority in culture, the cop, Amity chief of police Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), was the hero. Of course, the mysterious, multi-ton behemoth with teeth like razors and the dominion of the largely uncharted and inherently hazardous-to-humans ocean was the villain.

Now, a larger segment of American culture than ever is questioning the role of police (and whether such a role should even exist), and it’s clear to anyone who cares about marine life/the environment that sharks are to be conserved, not slaughtered. My, how times have changed.

Here’s what it feels like when you realize that in the years since its release, the ostensible hero and villain of Jaws have switched roles:

I’m not going to shit all over Jaws (but I am going to shit on it and around it, for sure), and I should make clear that it remains an effective monster movie. Turn off your brain and it’s fun, which is pretty standard procedure for a blockbuster. John Williams’s Oscar-winning shark theme (based around two tuba-blown notes) does the thinking and feeling for you. While I believe in my heart of hearts that sharks deserve our protection and aid, I’m not going to deny that they’re terrifying. I don’t want to be in the water with one, though I continue to think being consumed by one would be ultimately a terrific compliment. They supposedly don’t like the taste of human flesh, so if one thought I were good enough to eat all of, it would mean that I’m extraordinary tasting for a human. Such a flattering way to die, and you gotta go somehow. Also, it would make a great story and perhaps turn me into a legend. I’m just saying, there are worse things than getting eaten by a shark.

I was reading this little swim down memory lane about what it was like to be in Wildwood, New Jersey, a coastal resort town, during the summer of 1975 when Universal unleashed Jaws to the delight and terror of moviegoers. It sounds amazing. I’m sure it was truly exciting. I’d love to go back in time and experience that.

Jaws’s goodness is well-established and often visceral. If you know Jaws, you know the argument for its cultural importance and ability to excite. It seems rather redundant to spend much more time flattering a movie that a legion of moviegoers has already flattered and so for the sake of balance, let’s concern ourselves with its flaws.

Let’s start with the screaming decapitated head.

That’s… a screaming, floating, disembodied head. For all of Jaws’s cultural impact, we hear much more about it creating the summer blockbuster than we do it inspiring a million, cheap, fake-out jump scares.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-