Kelly Lee Owens's Techno Therapy

Entertainment

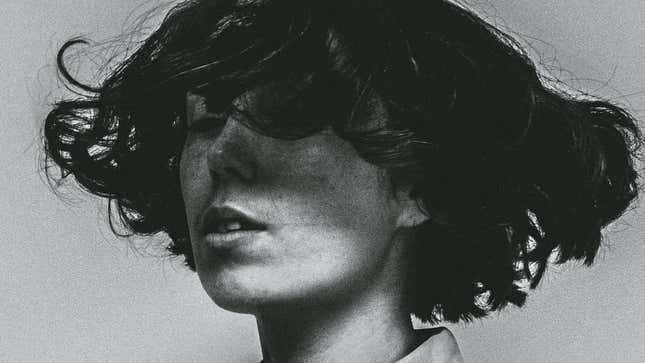

Photo: Kim Hiorthøy (courtesy Pitch Perfect PR

Kelly Lee Owens was on lockdown well before the rest of the Western world. Before quarantines began in Europe and the Americas in March, the producer/singer/songwriter had been holed up in a studio, mixing and mastering her full-length sophomore album Inner Song. Owens describes her approach to her spacious, dynamic techno as “obsessive”—she sculpts for “days on end” and put in 14-hour days during the album’s mixing. After months, she was ready to emerge.

“I was ready to do the other side of what I do, which is be out there and connect with people,” she told Jezebel in July via phone from London, where she’s lived for 11 years. And then: A global pandemic. It prompted Owens to delay the release of her album by about four months—originally announced for May 1, it finally dropped today. Lockdown also prompted Owens to pursue collaborative work like remixes and film scores. In the wake of the coronavirus, Owens, who turned 32 this week, was inspired to look inward and pause along with much of the world. “The first month or so I didn’t really do much,” she said. “It’s like checking in with that capitalistic mindset, the continually creating and producing something.”

Introspection was a familiar vantage point. Inner Song is about as personal and personable as techno pop comes. “Corner of the Sky” salutes Owens’s Welsh roots via a guest vocal from Velvet Underground founding member John Cale, who sings in English and Welsh. There’s an absolute banger, “Jeanette,” in which synths shimmer high and sub-bass rattles low, and in between is an expanse of open-hearted possibility. The song was named after her grandmother, who died last year, though she was still alive when Owens composed the instrumental track. “It’s one of those that kind of sounded like uplifting, uplifting, building, building, happy, and big,” Owens said. “And that was who she was: sunshine, open, energy.”

I went through a lot of losses and the most painful one was the loss of self.

When Inner Song is icy, it’s intentionally so, and because it includes samples of glacial ice melt to comment on global warming, as on “Melt.”—“I found samples, just FYI,” Owens assured me. “I didn’t go to the Arctic. That would be kind of ridiculous.” But thematically, the album’s focus is on healing. Owens describes the first track, an electronic cover of Radiohead’s “Arpeggi” as a kind of reemergence. “For me, it was personally coming up from the depths of something difficult that I’d been through,” she said.

She declined to specify exactly what difficulty she encountered. “I can’t. It’s too much, too personal to go into the depths of it,” said the preternaturally chatty Owens, who nonetheless attempted to elucidate while maintaining her vagueness. She compared the traumatic experience in question to “a lot of the things women experience universally that are still ongoing in relationships.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-