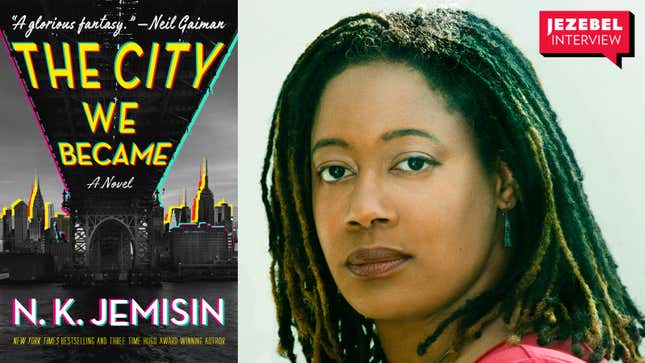

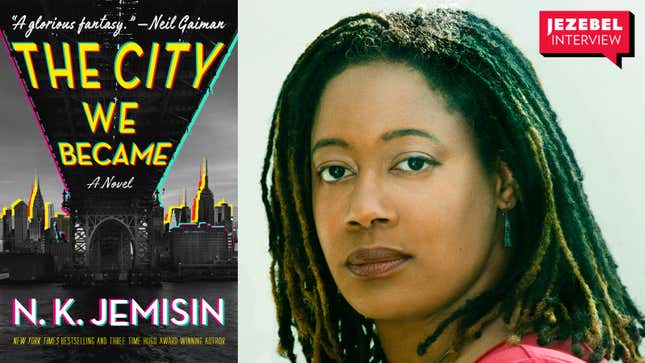

N.K. Jemisin's New Novel Is Both a Love Letter to New York City and a Warning

In Depth

The celebrated science fiction and fantasy writer N.K. Jemisin has become her generation’s greatest storyteller through ambitious and inventive world-building in novels like her Hugo Award-winning Broken Earth trilogy. Which is why her latest novel, the New York Times bestselling The City We Became, can feel like an anomaly in her body of work: Set in current-day New York City, her challenge was not to build a world, but to imbue our reality with a sort of otherworldly magic, illuminating certain truths along the way about the destructive forces that are present and at work in our lives.

The City We Became revolves around a conceit that likely feels true to anyone who has spent time in New York, or Hong Kong, or Lagos, or London. Cities can become alive, their streets arteries, their lifeblood and energy stemming from, as the antagonist in Jemisin’s novel derisively puts it with more than a tinge of racist hostility, their “hybrid vigor”—the collision of peoples, languages, histories that together, under the right conditions, can make something beautifully new and alien. The full sum of a city is somehow greater than its parts, and isn’t that their beauty?

That is, if the city is allowed to be born at all, for in the world of Jemisin’s novel, there’s a life form from a different dimension bent on killing earthly cities at the moment of their birth. In The City We Became, New York City has just come alive and is under attack. Tasked with keeping the newborn city living and breathing are six human avatars who embody the city as a whole and each of its five boroughs. Their alien enemy is personified in a bleached-out blonde called the Woman in White, who represents the destructive power of white supremacy and the blandness of an unchecked pro-development agenda, who spreads her ideology—call it a virus, if you want—throughout the city, person to person and building to building.

As Jemisin put it to Jezebel, the book is both a love letter to New York City as well as a “warning that we’re going to lose these things that we love” if the forces of unfettered real estate speculation continue to sanitize and smooth off the sharp edges of the city, turning the streets into into block after block of generic chain stores. It felt all the more eerie to read The City We Became in the midst of the covid-19 pandemic, with the city on life support.

“Obviously, I wasn’t anticipating the pandemic back when I wrote it,” Jemisin told Jezebel. But, she added, “I wanted to talk about the dangers in the city that I’ve seen, which is, I guess, viral in nature. It is insidious. It seems to slowly take over neighborhoods and kill them. I suppose it works very well as a metaphor, but it’s an economic thing that created destruction.”

Jemisin was supposed to be on a book tour for The City We Became; instead, she is, like many of us, holed up in her apartment, helping her more vulnerable neighbors buy groceries and worrying about an elderly aunt thousands of miles away. We talked about why she hates Hollywood depictions of New York City, how writing The City We Became felt like the “ultimate fantasy wish fulfillment,” and the follow-up to her novel, which will feature, in Jemisin’s words, a “New York politician who closely resembles some real-life people.” She remained mum on who exactly is the inspiration for her next antagonist, but as she wryly put it, “We’ve got some real choice ones here in New York.” The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

JEZEBEL: A lot of people have said that your new novel feels even more particularly resonant now. I think that people are feeling a lot of love for our city and feeling a lot of heartbreak over what’s happening. What inspired you to write a book about New York City?

N.K. JEMISIN: Obviously, I wasn’t anticipating the pandemic back when I wrote it. Mostly it was what I saw as a danger to the city that I have seen over the course of my life, because I’ve been living in New York on and off since I was five.

I wanted to talk about the dangers in the city that I’ve seen, which is, I guess, viral in nature. It is insidious. It seems to slowly take over neighborhoods and kill them. I suppose it works very well as a metaphor, but it’s an economic thing that created destruction. It’s meant to be a love letter to the city, but it’s also meant to be a warning that we’re going to lose these things that we love about New York if the situation continues.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-