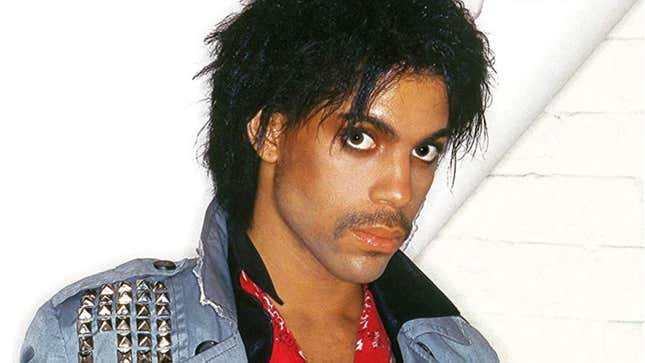

Image: Warner Bros.

Originals, the latest posthumous release of material from Prince’s vault, is practically infotainment. It works as well as a straight album of skeletal ’80s funk and balladry as it does a history lesson. On this collection of demos of songs eventually recorded by other artists (some hits, some deep cuts, almost all from the ’80s), we learn or are reminded of the vastness of Prince’s creativity at his peak, when the music was pouring out of him and he was grasping for any available container.

Some of those containers he crafted himself. Prince-conceived projects like Apollonia 6 (the second coming of Vanity 6 after Denise “Vanity” Matthews departed the trio) and the Time functioned essentially as puppet bands for not only his writing, but also his playing—listen to the demo versions of the Time’s “Jungle Love” and “Gigolos Get Lonely Too,” and you’ll hear virtually the same songs with Prince’s vocals where Morris Day’s eventually landed. Almost all of the instrumentation on those finished recordings by the Time was still performed by Prince (even when he wasn’t credited). This is true for many of the songs on Originals—the additions of an insistent cowbell and a ferocious approach to the drum kit by Sheila E., are mere adornments to the track that Prince laid out ahead of time with “The Glamorous Life.” That these songs in their demo forms sound so fully executed is evidence of stunning perfectionism, of the rough edges and icy sheen that ’80s pop accommodated. Prince happened at precisely the right moment.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-