The Downside to Earning More: Your Husband Is More Likely to Cheat

Latest

This just in from Cool, Bewildering News About How People Really Are: A study published in the American Sociological Review has found that one way to help cheat-proof your relationship is to make about the same amount of money as your spouse. Because, when one of you makes a lot more, the lower earner becomes more likely to cheat—even more so when that lower earner is a dude.

It’s garbage times we live in! But let’s not let our blood pressure shoot all the way through the roof, into the stratosphere, watch it transform into a literal giant fiery comet and then stand there helplessly as it rockets back down toward earth, the place holding everyone we’ve ever known or loved, to destroy everything. Because really, the news isn’t that bad if you’re:

- not even married

- are lucky enough belong to any other species except humans which would never get married in the first place on account of being more evolved

- have a unique ability to constantly adjust your earnings so that they are never too high or too low so that your spouse will love you correctly for all time

Oh, never mind, it’s still horrible.

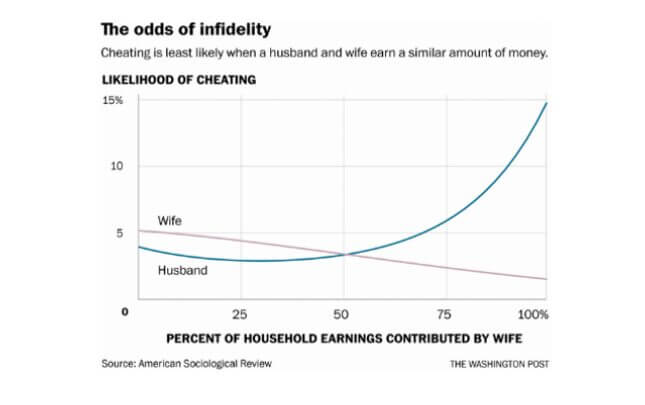

Over at the Washington Post’s Wonk blog, Max Ehrenfreund provides a handy chart that more clearly defines the contours of this horror:

Cool chart!

Ehrenfreund notes:

To do the study, Christin Munsch, a sociologist at the University of Connecticut, examined data for about 2,800 heterosexual married people under the age of 32 who participated in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a big federal research project, between 2001 and 2011.

She found that the less that men and women earned in income compared to their spouses, the more likely they were to cheat. This was especially true of husbands.

Men were also more likely to cheat if they made significantly more than their spouses, while women who made a lot more than their husbands were less likely to be unfaithful.

Munsch determined cheating not by asking people directly, because people lie—but based on marital status and the indicated number of sexual partners in the previous year, which people are apparently more comfortable with disclosing than saying it outright. Ehrenfreund:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-