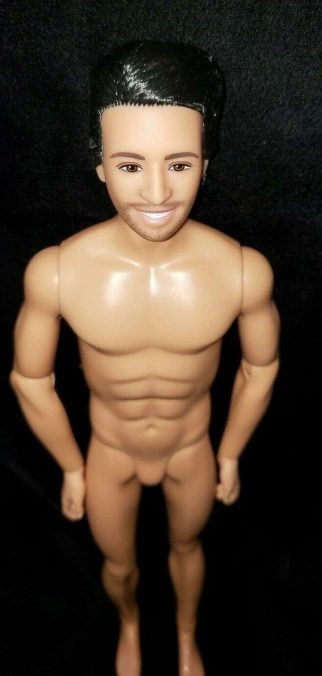

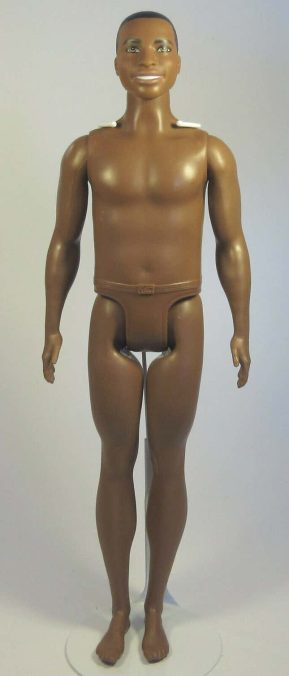

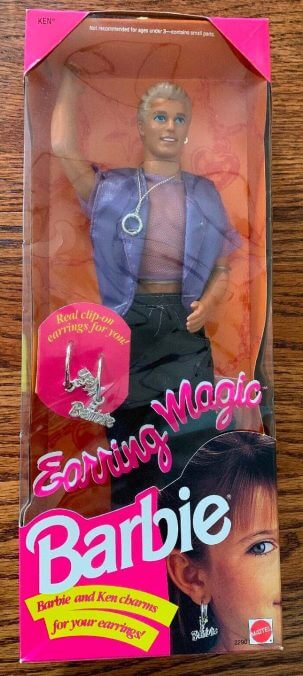

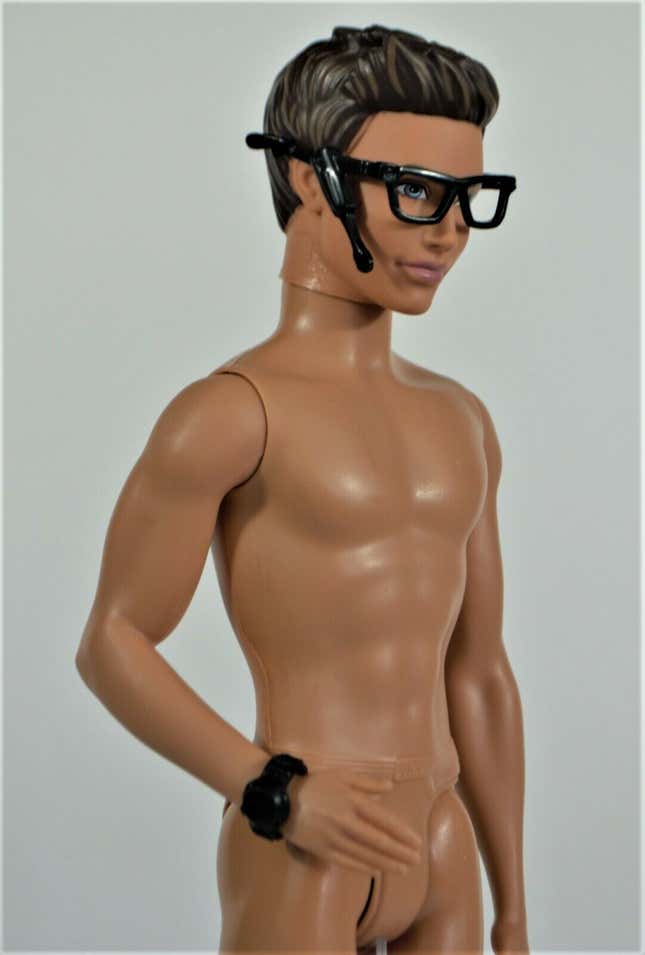

The thing about Ken is that he doesn’t have one. Mattel’s gentleman companion for Barbie, its Ken doll, came into the world without junk and remains that way. His lack of genitalia is a running joke: Ken is synonymous with dicklessness, as multiple references in pop culture attest—lines in Dogma, Sisters, and the 2016 reboot of Ghostbusters, to name a few. “Give Ken-Doll Crotch here two weeks, tops,” said the successful Derek (Adam Scott) of his manchild brother/new employee Brennan (Will Ferrell) in Step Brothers. And this isn’t just something people say in movies; earlier this year, the real-life Stephen Colbert described the equally real Rick Santorum as “Ken doll with even smoother genitals” on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

As a kid, I didn’t think Ken’s crotch was funny; I found it frustrating. Every ostensibly male doll I came across, and growing up with four younger sisters, there were a lot, I pantsed in the hope of an eyeful of plastic dick. As a kid growing up in the ’80s who very much wanted to look at penises—any penis, even a fake plastic penis would do—it was a rough time. Dicks were even rarer commodities in movies and especially on TV than they are today. It was especially maddening because there were no shortage of boobs to ogle, if only I had wanted to.

Every ostensibly male doll I came across I pantsed in the hope of an eyeful of plastic dick.

I had a sense of wanting to see dicks way before I had any sense of wanting to do anything with them or their owners, and it seemed unfair as an aspiring connoisseur that the entertainment around me gave me no access to the goods. Barbie had boobs, I reasoned crudely, having no idea that that her lack of nipples was what made them socially acceptable for children to look at. Why couldn’t Ken have a penis?

The answer, it turns out, is intricate and somewhat bizarre. Ken was not merely dickless by default; the bulge was the result of careful strategizing to which his inventors, businessmen, a psychologist, and Japanese manufacturers all contributed. Despite all this planning, Ken still came to represent things his parent company never intended, as icons tend to do. The story of Ken’s crotch is not merely one of PR, manufacturing, and/or branding—it’s about which realities our culture deems acceptable, and which that it seeks to keep hidden. This goes not just for the doll, but for the man he was named after, Ken Handler, who died in 1994 with major parts of his life airbrushed out of public view.

Ken (full name: Kenneth Sean Carson) was released in 1961 expressly to provide Barbie with a boyfriend. He was named after Ken Handler, son of Ruth and Eliot Handler, who ran Mattel. Ken Handler was a teen at the time of Ken’s debut. His legacy would become inextricably linked with the namesake doll that eventually he’d come to resent.

Like a perverted and plastic riff on the old chicken-or-egg cliche, Ken’s crotch was a key feature of his own conception. In his 1987 book Children’s Advertising: The Art, the Business and How it Works, former Mattel ad man Cy Schneider described the question of what to put between Ken’s legs as “a hot internal issue” and surmised that Barbie’s breasty appeal had something to do with it. Mattel’s Ruth Handler, who invented Barbie (based on the German Bild Lilli doll), wanted Ken at least to have a bulge, according to Robin Gerber’s 2009 book Barbie and Ruth. Handler thought that the design team lacked the guts to give Ken even the suggestion of genitalia, reports Gerber. Handler had been met with some resistance from Eliot as well as the design team when conceiving Barbie—the men felt that no parents would buy a doll with breasts for their children. They were wrong, she was right.

After pressing, Handler was able to persuade the design team to make mockups hinting at Ken’s genitals. Three were made: “One was—you couldn’t even see it. The next one was a little bit rounded and then next one really was. So the men—especially one of the vice presidents—were terribly embarrassed,” recounted early Barbie clothing designer Charlotte Johnson in M.G. Lord’s 1994 book Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll.

“None of us wanted a doll with a penis showing,” Handler is quoted in that book as saying. “If the child took off the swimsuit, we felt it would be inappropriate with an adult boy to show the penis—so we all reached a conclusion that he should have a permanent swimsuit.”

Johnson disagreed—she did want a doll with a penis showing and not some painted briefs: “Do you know what every little girl in this country is going to do? They are going to sit there and scratch that paint off to see what’s under it. What else would they do?”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-