The Ugly Necklace That Helped Bring Down Marie Antoinette

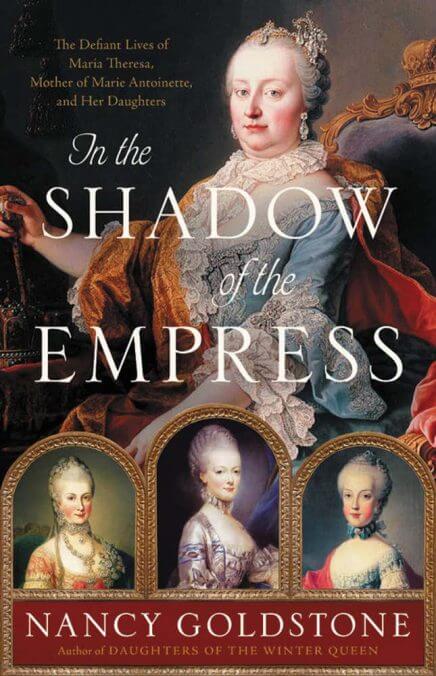

The backstory on the scandal that helped sink the French monarchy, in this excerpt from In the Shadow of the Empress

BooksEntertainment

Image: (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In the Shadow of the Empress traces the life of Empress Maria Theresa, the only woman to rule the sprawling Hapsburg lands in her own name, and her daughters—the most famous being her youngest, born Maria Antonia but better known as Marie Antoinette. This excerpt traces one of the many damaging controversies that erupted during her reign as Queen of France—the Affair of the Diamond Necklace.

“The case of the Necklace,” the comte de Mirabeau (soon to become a rising force in French politics) would later observe succinctly, “was the prelude of the revolution.”

It began with the arrival to Versailles in 1783 of Jeanne, comtesse de la Motte, a pretty woman almost exactly the same age as Marie Antoinette, who turned out to be one of the most adroit and enthusiastic con artists in the history of that lucrative profession. Although Jeanne’s title was fake—her husband was really Monsieur de la Motte, a man of unassuming birth and nonexistent fortune—she did have royalty in her family tree: she was a direct descendant of Henri II, one of the Valois kings who had ruled France two centuries earlier. (Two years before his death, Henri II sired an illegitimate son with a twenty-two-year-old paramour, much to the unhappiness of both his long-term mistress, fifty-eight-year-old Diane de Poitiers, and his wife, thirty-eight-year-old Catherine de’ Medici. It was this son, later recognized, whose descendants eventually produced Jeanne.) Knowledge of this princely lineage had literally been beaten into her as a child by her cruelly impoverished mother, who with each blow trained little Jeanne to beg for the family sustenance by crying out, “Pity a poor orphan of the blood of the Valois!” to the aristocratic carriages that flew past her in the street.

This harsh maternal indoctrination would be the saving of her; one day, one of those fine coaches stopped, and a tenderhearted marchioness took pity on the bruised and starving eight-year-old. She paid for Jeanne’s education, had the girl’s genealogy authenticated by the court, and even arranged for her to receive a small annual income of 800 livres from the royal treasury in recognition of her lineage. In that moment Jeanne, formerly a member of the disdained and forgotten French underclass, became Jeanne de Valois, a name that opened doors.

One of the doors it opened was to the magnificent château of the cardinal de Rohan. The Rohan family was one of the most prestigious and ancient in France. The cardinal was older, wealthy, and fatuous. Jeanne, now twenty-five, with extremely expensive tastes, recognized him instantly, in the universal language of grifters, as a mark.

At first, she just played him for small gifts of money. She would later claim that she had been his lover but he always denied it, and it didn’t seem to have been necessary, as she managed to string him along nicely without recourse to this expedient. But more than money, he gave her credibility. Soon, she had established herself and her husband, a man of similar integrity and love of high living, in a small apartment at Versailles. There, she took a lover named Rétaux de Villette, who, in addition to his other upstanding qualities, had a flair for penmanship. She then began boasting discreetly of a growing secret friendship between herself and Marie Antoinette, which she buttressed by the surprising revelation of a number of personal letters, written on high-quality paper adorned with baby blue fleur-de-lis, symbol of the throne, signed by the queen.

This caught the cardinal’s attention, as she had known it would.

Rohan was pining to gain entry to Marie Antoinette’s inner circle. The cardinal’s fortune was not what it once had been—a perplexing rash of bankruptcies had recently run through the aristocracy, even ensnaring some of Rohan’s relations—and it was becoming more and more difficult to live up to the grand standards of the past. Everyone knew that the surest way to riches was through the queen; those previously worthless Polignacs had proven that. Nobody could figure out what she saw in them and yet there they were, dripping with favors and treasure. But Marie Antoinette wouldn’t have anything to do with the cardinal de Rohan. He had once been ambassador to Vienna, and Maria Theresa had seen through him in an instant as a worthless flatterer and libertine, and had warned her daughter against him. Marie Antoinette shared her mother’s opinion of the cardinal. Up until now, he had been frozen out at court.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-