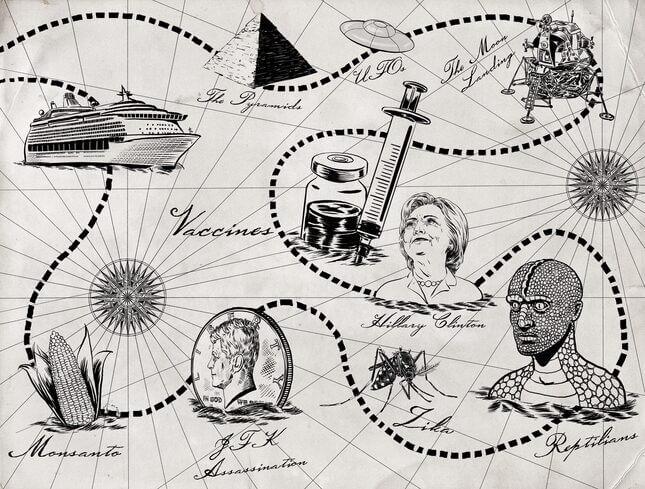

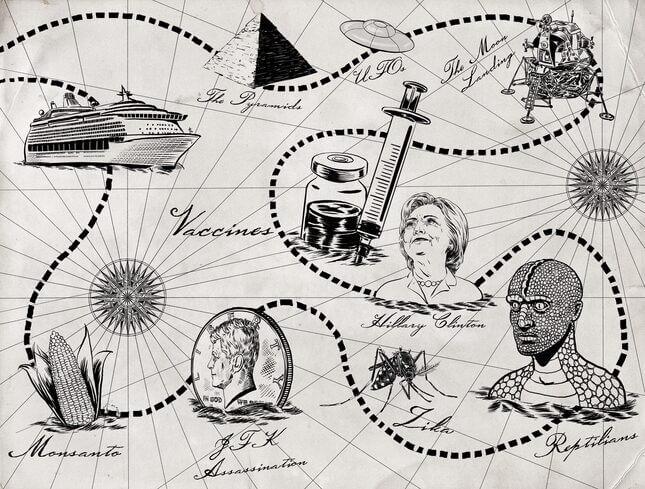

Sail (Far) Away: At Sea with America's Largest Floating Gathering of Conspiracy Theorists

- Copy Link

- Bluesky

“Once we’re in international waters, every woman on the ship gets to make love to whoever she wants,” Sean David Morton said, with a wink.

It was not entirely clear why we couldn’t have done that already, where we were, sitting immobile on the Ruby Princess, a “grand class” yacht moored in San Pedro, California, an oil refinery and port town just south of L.A. But we were making ready to sail away from our conventional ideas about laws, up to and including the laws of cause and effect.

Morton is a radio host, among other things. Here he was claimed to be one of the lead organizers of Conspira Sea, the first annual sea cruise for conspiracy theorists. While the ship looped from San Pedro to Cabo San Lucas and back, some 100 of its passengers and I would be focused on uncharted waters, where nothing is as it seems. Before we docked again, two of them would end up following me around the ship, convinced I was a CIA plant.

Elsewhere aboard, people’s vacations were already exuberantly underway, the cigarette-browned casino bustling. Those of us in the conspiracy group were crammed into a dim, red-carpeted conference room in the bowels of Deck 6 to hear Morton, a Humpty Dumpty-shaped man with a chinstrap beard and an enormous, winking green ring, explain our mission.

“Conspiracy theorists are always right,” Morton told the room. He spoke with the jokey cadence and booming delivery of his profession; he’s basically Rush Limbaugh, if Rush Limbaugh claimed to have psychic powers (Morton practices a form of ESP known as “remote viewing,” which he says he learned from Nepalese monks). It was a bit of a pander, since the room was filled with conspiracy theorists.

“In 40 years,” Morton added, “as many people will believe a bunch of Arabs knocked down the World Trade Center as will believe that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.” A lot of people nodded.

The things that everyone thinks are “crazy” now, he said, “the mainstream will pick up on them. 2016 is going to be one of those pivotal years, not just in American history, but in human history as well.”

A solemn hush settled. Morton switched gears. “Did you hear about Deflategate?” he asked. “Those footballs were in an elevator with Ray Rice!” (The New England Patriots had been accused of illegally deflating footballs, I guess the joke was, the same way former Ravens player Ray Rice knocked his fiancée unconscious in an elevator). No discernible reaction. He tried again: “What do Brokeback Mountain and Dallas have in common? They both have cowboys who suck!” That one got a light ripple of laughter.

The Conspira Sea was conceived of and organized by Morton and Dr. Susan Shumsky, a no-nonsense New Age Jill-of-all-trades with long blonde hair and an excellent pair of rhinestone-spangled cat-eye glasses. (Update, March 2: While Morton claimed aboard the ship to have been helped to organize the Conspira Sea, Shumsky says that is false: “The cruise was NOT conceived or organized by Morton.” Shumsky was solely responsible for organizing the cruise, she adds.)

Morton, the de facto master of ceremonies, was introducing the conspiracy cruise presenters for 15-minute individual previews of what they would be teaching in our week at sea. (The presenter schedule was removed from the internet soon after the cruise ended, but a cached version is available here.)

There was Helen Sewell, a British astrologer, and her husband Andy Thomas, a conspiracy researcher. There was Jeffrey Smith, an anti-GMO activist with no scientific credentials and a previous career in “yogic flying.” There were Sherri Kane and Leonard Horowitz, a team in both research and life, who were there to tell us how the media and the CIA control the gullible populace.

There was Laura Eisenhower, the great-granddaughter of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a fact that sometimes would seem significant and sometimes would not. She explained she was there to show us how to get beyond “the seven chakra system that’s been implanted within us,” and a bunch of other similar phrases I found hard to follow. There was Nick Begich, the son of the late Alaska congressman John Nicholas Joseph Begich, a low-key, sweet-natured guy who believes the government is controlling both the weather and people’s minds with the use of a research program called HAARP.

Near Begich was Winston Shrout, who runs a staid-sounding financial advice company called Solutions in Commerce, dedicated to the idea that the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve have us all literally enslaved. A few seats down was Dannion Brinkley, who’s from South Carolina, and who has died and been to Heaven three times. Death, he told us, is not, in fact, real.

“That’s the biggest buncha crap on Earth,” Brinkley said disgustedly, of the idea of death. “It never happens.” The ultimate conspiracy, if you will.

Most notably, there was Andrew Wakefield, the British gastroenterologist who authored the now-infamous 1998 study that suggested there might be a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Jenny McCarthy was breathed into being because of Andrew Wakefield.

The wider world hasn’t been kind to Wakefield, who lost his medical license in 2010 and is widely described as a one-man public health disaster. Here, though, he was treated as a battle-scarred hero. The room hung on his every word.

“One in two children will have autism by 2032,” he told us, to horrified gasps. “We are facing dark times. The government and the pharmaceutical industry own your bodies and the bodies of your children.”

“There are no [vaccine] exemptions anymore,” Sean David Morton piped in. “Not even if you’re Jewish. But I think Obama made an exception for Muslims.” He switched into what may have been an impression of someone with an Arabic accent: “Ay yi yi!”

“That’s the biggest buncha crap on Earth,” Brinkley said disgustedly, of the idea of death. “It never happens.” The ultimate conspiracy, if you will.

He dropped back down to his normal register. With vaccines, he said, “They rape your kids. They are literally raping your kids. They literally jam something into their bodies that makes them sick.”

The presentations wrapped up and everyone started to drift away, just as the boat lurched into motion. Morton nodded darkly.

“It’s not all a great big beautiful tomorrow out there,” he assured the departing crowd. “That much I can tell you.”

At full capacity, the Ruby Princess holds around 3,084 people in 1,542 cabins, plus a 1,200-person crew. It has three dining rooms, four pools, an outdoor movie screen, a spa, a wedding chapel, a teen center, a nine-hole golf course, an art gallery, daily Alcoholics Anonymous meetings on deck 16, and a small library with the best in Lonely Planet guides and dog-eared thrillers. Inside the ship’s beating heart—a large, white marble-floored three-story atrium, decorated with a white grand piano and ringed with shops, and, because we were heading to Mexico, occasional musicians in mariachi outfits—there’s a Future Cruises kiosk. Once onboard, you must anxiously ponder how quickly you can return.

For most of the trip, except when docking for day trips in the most tourist-friendly parts of Mexico, the boat would be bounded on all sides by an endless, horizonless expanse of deep blue ocean. It was, as it turns out, quite soothing to look at after a long day of having your belief systems shaken relentlessly by the gale-force winds of alternative truth.

The Conspira Sea presenters came in two kinds: The spiritual ones talked about the heavens, angels, and their effects upon us. The earthly ones mainly talked about vaccines, which are bad and inescapable, or debt and legal issues, which are bad but can be beaten.

Earthly concerns commenced early on a Monday morning with Andrew Wakefield, down in the green-carpeted Botticelli dining room. He was in a dour mood.

“The story of my life is that I had a promising career and I flushed it down the toilet,” he said. He wasn’t overstating things: Wakefield was a gastroenterologist in London in 1998, when he and a dozen co-authors published a piece in the Lancet, claiming that eight of 12 children they’d studied had developed behavioral symptoms associated with regressive autism after receiving the MMR vaccine. The study didn’t definitively state there was a link between the MMR and autism, although now Wakefield says he believes that to be the case.

The Lancet retracted it in 2010, and 10 of Wakefield’s 12 co-authors wrote a subsequent retraction that doubled as an apology for creating conditions in which an untold number of parents became afraid to vaccinate their children. Wakefield lost his license and was accused of having been working on patenting an alternate measles vaccine of his own and of being paid by a personal injury lawyer. (Wakefield called those reports inaccurate and done with bad intent. In 2007, he sued Brian Deer, the journalist who wrote the investigative pieces about him, for libel, but eventually dropped the case. He later sued the British Medical Journal, where Deer’s stories were published, as well as Deer personally for defamation in Texas; that suit was thrown out in 2014. A judge ruled state courts there didn’t have jurisdiction over a British publication.)

Wakefield’s belief in his own theories has never wavered. He has an intense following among parents who believe their children were injured by vaccines (one told the New York Times in 2011 that he was “Nelson Mandela and Jesus Christ rolled up into one”). In a presentation that lasted an hour and a half, Wakefield told the cruise audience that the Centers for Disease Control was ignoring evidence that the MMR vaccine increases autism rates, especially among African-American boys. His main source, a CDC whistleblower, has said in a statement that he “would never suggest that any parent avoid vaccinating children of any race.”

Wakefield disagrees: He predicted a future where “80 percent of American boys” will have autism in 15 years.

And, like every other presenter, he also had something to promote: a film called Injecting Lies, which he said will be released in April and is intended to shame and alarm “the mainstream,” particularly the California liberals who supported SB 277, the law that in June 2015 made vaccinations mandatory for children attending schools and daycares. The hope is that the movie will spur the public to demand a Congressional hearing on vaccine safety.

I clearly heard Wakefield say during the presentation that Leonardo DiCaprio was somehow involved in helping to promote the film, having gotten involved via his father George. “They’re going to put all their efforts behind it,” Wakefield told the room.

(When I asked Wakefield about the DiCaprio claim later, he denied having said it, and said I must have misheard, though other reporters in the room confirmed they’d heard it too. A representative for DiCaprio didn’t return a request for comment.)

Compared to many of the presenters, Wakefield was quite coherent, with a thesis that hung together in a logical way, at least on the surface. It was easy to see why he’s a star in the anti-vaccine world.

The question was why he was delivering a passionate defense of his life’s work not to the medical establishment, but to an audience mainly composed of retirees, in a dining room, on a boat, in the middle of the sea. The ceiling thumped; we could hear strains of music and the faint, energized cries of a Zumba class in progress.

When Wakefield opened the floor to questions, the conversation began to drift casually into the “12 alternative doctors murdered last year,” presumably by the government, which made them all look like suicides. At this point, I had to take a walk on deck and stare very hard at the ocean, because I suddenly had a terrible headache. It could have been seasickness, I suppose.

Head still throbbing, I went to see Winston Shrout and Sean David Morton, each discussing strategies to get out of debt and deal with (outsmart) the court system. In lieu of paying fines or civil court judgments with money, the way most people might, they talked about writing promissory notes and bonds and liens and submitting them to the court.

Morton’s argument, which I had to hear a few times before I fully got, was that it’s possible to become a “de jure state national,” someone who isn’t subject to federal law—and, by extension, is free from federal courts, taxes, and criminal charges.

This turned out to be a window into a fascinating, tiny segment of financial conspiracy theory. Both Morton and Shrout said things that suggested they are part of what’s called the “Redemption Movement,” which holds, among other things, that each U.S. citizen has a secret “straw man” bank account, created at birth and owned by the U.S. government, which you can gain access to if you file the right paperwork. Proponents of redemption theories also frequently claim that U.S. law is null and void, that the only valid laws are the Bible or the Uniform Commercial Code or maritime law. (The IRS has issued a lengthy, irritable response to what it calls “frivolous tax arguments.”)

Redemption theory does not have an extensive track record of success. Its founder, Roger Elvick, spent time in federal prison for filing false tax returns (as well as at least one involuntary inpatient stint in a psychiatric hospital).

Morton boasted that he’s “taken on the IRS, the SEC, the DMV” and numerous other entities “and won,” which was an interesting way to put it, as he was sued by the federal Securities Exchange Commission in 2010 and accused of $6 million in securities fraud. The feds said he’d solicited investors to a hedge fund by claiming to have psychic abilities.

In 2013, a federal court entered a default judgment against Morton, his wife Melissa, and a company owned by them, the Prophecy Research Institute, for more than $11 million. The SEC sent out a press release noting that the Mortons “never properly answered” the allegations against them, responding instead with odd and far-fetched legal filings:

“[T]he Mortons filed dozens of papers with the Court claiming, for instance, that the Commission is a private entity that has no jurisdiction over them, and that the staff attorneys working on the case do not exist.”

The same year, Morton filed for bankruptcy, which he told me was unrelated, a tactic to keep from being evicted by an unscrupulous landlord.

The Mortons’ legal woes are by no means over: This past September, they allege in court filings, they were raided by IRS agents, who held them at gunpoint, then took their computers, cell phones, a mass of files, and their marriage license, all of which they were storing in one of their cats’ bedrooms.

This incident, too, went unmentioned in Morton’s presentations on his triumphant path to financial and legal freedom. It would become a significant issue for the Mortons just after the cruise ended.

The same dizzying day, I caught the last moments of a talk by Dannion Brinkley, the man who’d died three times (lightning, during heart surgery, and during brain surgery).

But “dead” is a relative term: Brinkley’s taken numerous tours of heaven and has come to realize that no one ever truly dies. While he was there, he said, he was shown several prophecies, all of which have come true, including Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the Chernobyl disaster, and the September 11 attacks.

The first time he died, back in the ’70s, was the most transformative, Brinkley told me: “I went from a complete arrogant redneck hillbilly asshole former Marine to a spiritual being.” (Brinkley has been accused of exaggerating his military service, claiming to have been a CIA sniper in Laos when he was, as the L.A. Times reported in 1995, actually stationed in Georgia driving trucks.)

Brinkley also hugs people, diagnosing by touch what’s wrong with them, physically or spiritually. After his talk, he received a long line, massaging one lady’s hands and telling her to check her sugar, then pronouncing that another one of the reporters on board was not “appreciating herself” enough.

He embraced me last. He rubbed my lower vertebrae vigorously, then suggested that I consider switching “from the written to the visual.”

“You’ve come as far as you can in this job frame, this trajectory,” he said.

After our hug, we chatted. The thing that links everyone on board, he told me, is simple: “We’ve been around long enough to know most of what we’ve heard is a lie. Everyone here is on a search for what is real.”

Onboard, there was surprisingly little talk about current events or politics. Even the occupation of Malheur Nature Preserve didn’t come up until I mentioned it one night at dinner. (To be fair, internet was like 75 cents a minute and I didn’t see many newspapers onboard.) Perhaps the idea of getting invested in who’s going to win the presidential election seems ludicrous when you’re considering a dystopian near-future of forced vaccines or the New World Order trying to depopulate the globe.

Laura Eisenhower did note during her presentation, however, that no one should vote for Hillary Clinton: “She’s definitely not human.”

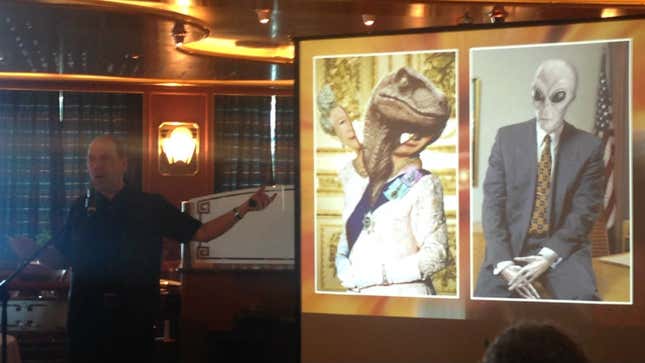

Eisenhower was one of the presenters on the spiritual side, delivering a history lesson, more or less, about a vast intergalactic war. There are at least three different types of angels, by my count, as well as Reptilians (giant lizards) and “dark energy” beings called Dracos. Fairies were mentioned in passing.

It seemed garbled, but the audience was rapt, and the ideas seemed largely harmless. The same went for Susan Shumsky, the trip organizer, who gave several presentations on energy and auras and positive thinking, and for Andy Thomas, the delightful English “unexplained mysteries researcher,” who phrased everything as a question. Maybe the pyramids were built by extraterrestrials? Wasn’t September 11 maybe a “New World Order attack,” designed to make us “even more fearful”? Could Hillary Clinton be a member of The Family, also known as the Fellowship, the powerful, shadowy collection of evangelical politicians? (Actually, she could, kind of: The Family is real and Clinton has attended meetings.) And doesn’t the moon landing seem a little fake?

“I certainly hope the moon landing was real,” Thomas murmured, regretfully. “I was quite excited about it when I was a boy.”

It was a relief to be hearing theories that didn’t matter. Do we care at this point if the moon landing took place in a TV studio, or if the British royal family are actually giant reptiles? Compared to the people who don’t want you to vaccinate your kids, the stakes feel rather low.

Thomas seemed significantly less tortured than many of the people on board, presenters or attendees.

“Meeting so many of you is lovely,” he told his audience, beaming at them. “So is realizing we’re not alone. Unusual beliefs aren’t so unusual. They just don’t get talked about so much. The mainstream media won’t talk about the things a lot of us believe. I absolutely think there’s a program to keep us uninformed.”

But there is hope, Thomas added. “You can live without fear. I do believe we’ll turn all this around.”

By contrast, the anti-vaccination crowd, though often friendly and personable in conversation, trafficked entirely in fear.

Sherri Tenpenny, a warm, chatty Ohio osteopathic physician, aimed to warn us about the 141 new vaccines that are currently in development, which could potentially be foisted upon all adults by 2020. Tenpenny is a star in the anti-vax world, and several attendees were specifically on the cruise to see her.

Vaccinations, Tenpenny said, have been “a dirty rotten business” for the entire 200 years they’ve existed. She argued that smallpox and polio killed far fewer people than has been commonly reported, and that while measles can be fatal to infants, it doesn’t happen all that often. Vaccines, meanwhile, can cause lifelong health problems, she said. She was furious about the California vaccination measure, warning there will soon be other, similar laws.

“It’s really no different than Nazi Germany,” she said. “The only difference is that we don’t have a number on our arms.” She handed out flyers depicting the cover of her forthcoming book: the words THEY’RE COMING FOR YOU NEXT, over a picture of a lab-coated figure extending a hypodermic needle.

Tenpenny’s lectures went slowly, plagued by technical issues. Throughout the cruise, power cords were missing, projectors would break, slides would freeze. At one point a booming announcement from the captain broke in, letting us know what the CDC had to say about the Zika virus. More than one person suggested, not quite joking, that all of these things were also a conspiracy.

While we waited for Tenpenny to come back online, Andrew Wakefield glided over and introduced himself, having discerned from my feverish note-taking and pained facial expressions that I was a reporter.

Wakefield was weary, polite, and charming, with the relaxed shoulders of a man who’s already lost everything. He was on the cruise with his wife Carmel, a former physician turned classical music DJ; they now live in Austin with their four children, and have been involved in a series of autism-related enterprises, most recently the Autism Media Channel, a documentary film concern. When not watching the presentations, he told me, he was doing yoga.

“Gawker Media,” he said, dryly, with a little smile. “They’ve never been particularly sympathetic to us.”

I agreed that was true.

“Is that the kind of story you’re writing?” he asked, neutrally. He added that it didn’t really matter what I was planning, since my editors and my advertisers and their “backers” are the ones in charge, and that he feels sorry for “you guys,” meaning reporters.

I thanked him for his concern.

Wakefield seemed philosophical about everything: his wrecked career and ruined reputation, as well as being on a boat alongside presenters talking about angels and Reptilians.

“If you offend the pharmaceutical industry, this is what happens,” he shrugged. “But I’ve never committed fraud in my life. Everything I said in that paper has turned out to be true.”

“But aren’t you, in a way, here to dig your name out of the muck?” I asked.

“I’m not here for redemption,” he said, flatly. “I’m in it to get the truth out.” Moreover, he added, “I’m never going to go away. I have no interest in what my colleagues think of me.”

He turned to Shumsky, who’d just appeared, and they started having a quiet conversation. I wandered back out into the atrium, where an exuberant Englishman was doing a “martini demonstration” for a crowd of ordinary vacationers who were literally screaming in excitement.

“If you offend the pharmaceutical industry, this is what happens,” he shrugged. “But I’ve never committed fraud in my life. Everything I said in that paper has turned out to be true.”

It would probably please the conspiracy theorists to know that midway through the cruise, a secret meeting took place. It was in my room. Information was shared, and snacks were served.

For the first few days, I’d had the impression that nobody gave a shit about me or the other reporters onboard. Most of the presenters were unfailingly welcoming and friendly. Anti-vaccine activists talked to me even after I revealed myself to be pro-vaccine. Sean David Morton found out I thought his sense of humor was a bit offensive and somewhat racist—because I accidentally said so right in front of his wife Melissa—and continued to be as polite as he could manage.

One night, I ate dinner beside Michael Badnarik, the 2004 Libertarian candidate for president, who makes a living these days lecturing on the Constitution. In the 1970s, as a young man, Badnarik had a dispute with the IRS that set him on a new course: He hasn’t paid taxes since 1994, refuses to get a driver’s license, and carries an unlicensed firearm. He allows people to pay him in silver for his speaking engagements: “When the government falls apart, I’ll still be able to buy food.” He also wants Texas, where he lives, to secede from the United States, and he plans to run for the presidency of Texas afterwards.

Badnarik declined to go on shore in Mexico. “It’s a lawless society,” he explained.

We argued good-naturedly for two hours. I had questions about his insistence that the Republic of Texas would somehow be a better or less corrupt government than that of the United States. By the end of it, he was calling me “sweetheart” and I was asking worriedly how he intends to take care of himself in a few years’ time, given that he’s unmarried, childless, and absolutely doesn’t believe in Social Security or Medicare.

“I probably don’t have to worry about retirement,” he said lightly. “I’ll probably be killed in a shootout with police.” It was hard to tell exactly where the joke began.

But all was not well elsewhere in our tiny press pen. Aside from me, there was a two-person camera and writer team from Refinery 29, who mostly kept to themselves and got off the boat two days early. There was also a team from Popular Mechanics, reporter Bronwen Dickey and photographer Dina Litovsky, who stayed the whole time, as did Colin McRoberts, a former attorney. His wife Jennifer Raff runs a blog called Violent Metaphors, where she writes about pseudoscience and scientific literacy. She was fascinated by the cruise, but unable to go because of her schedule as a teacher. McRoberts, who now works as a consultant and is writing a book about irrational beliefs, crowd-sourced the money to buy his ticket and came instead.

At first, both McRoberts and I were let pretty much alone, even though I introduced myself as a reporter constantly and he was blogging about the cruise each day. We sat in lectures and no one asked us to leave or even really seemed to notice we’re there.

McRoberts and the Popular Mechanics ladies and I sat down to chat in one of the ship bars one afternoon to get to know each other. We promptly got spooked someone might be watching us and moved to my room.

“We’re becoming just like them,” Litovsky said wryly, as we waited for the elevator. We all shushed her.

“I probably don’t have to worry about retirement,” he said lightly. “I’ll probably be killed in a shootout with police.” It was hard to tell exactly where the joke began.

Once in my cabin, Litovsky and Dickey said they were having a very different experience, due mainly to an article Popular Mechanics had published in 2014 about junk science, which set off everyone’s conspiracy siren. Almost immediately, they were getting cold-shouldered in a fairly nasty way, unceremoniously kicked out of a panel debate between Wakefield and Jeffrey Smith about the causes of autism (vaccines or pesticides was the sticking point), after being told that it was “not for media.” Wakefield was certainly not gliding up to them to discuss his yoga practice; instead, he reportedly kept asking them around the ship why they were really here.

“I’m pretty worried about what Popular Mechanics is planning,” Ted, the guy videoing the sessions, told me at one point. He was a devotee of Burning Man, and dressed in a uniform of colorful pajamas, to which he occasionally affixed a fuzzy, homemade tail. “They do a lot of conspiracy debunking.”

“They seem like nice women,” I told him.

“Yeah, but you never know,” he said thoughtfully. “Some of the conspiracies they’ve debunked probably deserved it, true. But a lot of them I still believe.”

A study published in the American Journal of Political Science estimates that 50 percent of Americans believe in some form of conspiracy theory: The CIA invented the crack cocaine epidemic. 9/11 was an inside job. Fluoride is seeded into the water supply to make the public easy to control.

The political scientists Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood, who authored the study, argue that conspiracy theories are, at their core, an attempt to deal with emotional distress, the kind caused by a shocking or inexplicable event: a vicious new drug coming out of nowhere, planes demolishing the World Trade Center, the president shot dead on a sunny day, riding through the streets of Dallas. Conspiracy theories provide a soothing order and, with it, reassurance.

But there’s also a reason why Americans are particularly prone to believing in conspiracy theories: In our case, quite a lot of outlandish things turn out to be true. The CIA really did conduct serious research into whether it could use mind control on its enemies, a program known as MKULTRA; it really did try to assassinate Fidel Castro through an increasingly absurd series of weaponized devices (exploding cigar, booby-trapped seashell, ballpoint pen laced with poison). The U.S. Army really did try to use elements of the “human potential” movement to try and develop “psychic spies,” known as the Stargate Project. The FBI really did run the COINTELPRO program, a series of covert operations designed to undermine and destroy political organizations from within.

And Merck, for what it’s worth, really is embroiled in an actual controversy over the MMR vaccine, albeit not one that has anything to do with autism. It is currently being sued by two former virologists, who filed suit in 2010 claiming that the company falsified data about the vaccine’s effectiveness rates against mumps, which they say has declined over time. That case is still in litigation.

The fact, then, that the folks on this boat believed some interesting stuff isn’t necessarily unusual or inexplicable. But aside from a consistently anti-vaccine slant, there wasn’t one underlying theme connecting the conspiracy theorists onboard to one another.

It was like being in a church revival with 20 different denominations shouting for your attention. I kept a running list in the back of my notebook of things that are, definitively and by all accounts, bad. By the end it read something like a paranoid Wikipedia search history:

– Vaccinations

– Mainstream media

– Merck

– The court system

– Monsanto

– TV

– Advertising

– Prescription drugs

– The legal system

– American Express

– Quicken Loans

– Negative ego

– Bill Gates

– Surveillance

– The World Health Organization

– The Centers for Disease Control

– George W. Bush

– Barack Obama, probably

– Hillary Clinton, almost definitely

If there was one consistent idea, it was that we’re all caught in a bewildering and vicious system. Someone is the oppressor, whether it’s the Illuminati or someone from the WHO trying to stick you with needles. Something must be escaped, mastered, transcended. If you’re lucky, and have the right set of tools and devices—more on those in a minute—you can break free. Even mortality and death, in this context, are little more than a vicious game, one that can be beaten.

Despite the noticeable British presence, there was something distinctly American about this, a potent mixture of self-improvement, self-delusion, get-rich-quick hopes, anti-establishment fervor, and shameless snake oilery. The cruise was the spiritual descendant of a 19th-century medicine show, where traveling non-doctors hawked a variety of pills and potions to an enraptured and desperate audience.

And many people onboard truly were desperate. Bits of tragic stories leaked out: Children they believed were injured by vaccines. Dragging legal challenges and catastrophic debts. Their homes were at risk, their credit wrecked, their spiritual foundations wracked. They were looking for a moment of connection, a last-ditch way out.

“There are people here who fear for their lives,” an attendee said, an older white man who begged me not to use his name. “Some of them have been persecuted to the point of being prosecuted. They came here to figure out how to get out of where they are.”

To that end, a lot of the presenters had multiple lines of business: Sean David Morton, for example, is a psychic and a self-styled legal expert, but he also does Tarot and “cartomancy readings.” He spent part of one presentation recommending vitamin supplements and various treatments at a hospital he’s familiar with in Tijuana.

Sherri Kane and Leonard Horowitz, who refer to themselves as investigative journalists and documentarians, also sell things. They’re a good-looking pair, smiley and energetic. Most of their first presentation centered around how Hollywood is working with the CIA and people from “high levels of government” to exert mind control on the populace, who exist in a state of “psychotronic delirium.” Together, they were an Internet banner ad come to life: ONE WEIRD TRICK THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW ABOUT THE GOVERNMENT.

Horowitz describes himself as a former dentist and public health expert, and he and Kane were selling numerous supplements, chiefly OxySilver (water with a small amount of silver in it), and Liquid Dentist (mouthwash, I think). They also handed out a 12-page catalogue of other items one could purchase: books, DVDs, healing clay, something called Love Minerals™, a small tuning fork to relieve stress, a giant one to clear energy blockages, and a substance called PrimoLife, filled with “monoatomic elements vibrating with LOVE.”

Horowitz and Kane told me later that, while they have a complete money back guarantee, nobody in their memory has ever asked for a refund.

“Because it works,” Kane explained.

“Could that lady please stand up?” Sherri Kane was pointing at me. She was smiling, although it didn’t quite reach her eyes.

We had two days left in the cruise, and we had reached the moment where the shit truly hit the fan. Somehow, this came as a surprise to me.

The chaos began at a movie screening, a film about the terrorist attacks in Paris by Kane and Horowitz. (Not to give too much away, but they believe the attacks were a false flag, orchestrated by the Qatari government in cooperation with the talent agent Ari Emanuel, Rahm Emanuel’s brother. It’s all part of a “global depopulation” effort.)

Before the film began, Kane pointed me out and dramatically requested that I reveal who I work for. I’d already introduced myself to a majority of people in the room, but I did it again.

After the film, things got weirder: Kane and Horowitz called Litovsky, the photographer, to the front of the room and accused her of taking photos of the wrong parts of the movie, the parts with photos of the websites where they sell their products.

“Why would you take photos of our sponsors?” Horowitz demanded. “HealthyWorldStore.com?”

Suddenly, everyone was yelling. Kane and Horowitz were yelling at Litovsky. Other people were yelling at them to stop. A lady got up and yelled that the flash from the camera made it hard for her to concentrate. The group’s yoga instructor, Abbie, an incredibly nice woman who happens to be Shumsky’s niece, yelled that Horowitz and Kane were guaranteeing a negative article.

“They could’ve written something really nice about this cruise, and now it’s going to be a negative spin, because of what you did,” she shouted. “You humiliated them!”

“Who are you?” Kane demanded.

“She’s a plant!” a woman yelled from the audience.

“She’s the yoga instructor,” Shumsky corrected, who’d come in during the middle of all this and was trying, occasionally, to intervene.

Suddenly, everyone was yelling. Kane and Horowitz were yelling at Litovsky. Other people were yelling at them to stop. A lady got up and yelled that the flash from the camera made it hard for her to concentrate.

It went on for an agonizingly long time, but finally, everyone seemed to run out of steam. The reporters carefully left the room as a group and repaired to a bar. Afterwards, close to midnight, I went downstairs to the Internet cafe. I was sitting at a computer terminal when all of a sudden, Kane and Horowitz were standing over me with a camera.

“Did you follow me?” I asked. They said no. I felt unconvinced.

“Tell everybody who you work for,” Kane bellowed, holding the camera.

“Who owns Jezebel?” Horowitz added. “Do you even know?”

They wanted to know why I was here, if I was part of the “belligerent media” who intend to smear them. Horowitz wanted me to know how badly his reputation has been damaged after his work “exposed the Hepatitis B vaccine as being the origin of HIV/AIDS.”

They asked how I felt about vaccines. I told them I’m fairly traditional, in that I think they’re a good idea. Kane had me repeat that one several times for the camera.

Over the course of an hourlong conversation, Kane and Horowitz relaxed somewhat, although they continued filming me (and I began filming and tape-recording them, meaning we were all standing there, pointing phones and cameras at each other). We talked about Americans’ undermined trust in the government and how difficult it is to have ideas that are far outside the mainstream.

They told me I was making them nervous, but they understand it was probably unintentional. We were communicating on a human level, and it felt like a bit of a breakthrough.

And then, somewhat casually, Horowitz suggested that maybe I worked for the CIA.

“Intelligence agencies that are operating on behalf of big pharma, big biotech and big banking need intelligence,” he explained. “They need to know what we’re thinking and what we’re doing.”

“I definitely do not work for an intelligence agency,” I told him.

“Well,” Kane interjected. “Sometimes people don’t even know they are.”

“I’m pretty sure I would know,” I told her.

“I would guarantee you, based on evidence, that you’re given intelligence on a need-to know basis only,” Horowitz said. “Here’s the structure: You’ve got some high level J. Edgar Hoover types who are in charge of MKUltra, COINTELPRO, and then they have underlings and assignments. They’re not told the whole picture. This is seen even in Hollywood films.”

He asked if perhaps the “sheikh of Qatar” has just bought shares in Gawker Media (I had told him that we had recently taken on outside investors). I tell him the sheikh had not. He told me the “intelligence community” frequently hires “young journalists” to do their dirty work.

I felt as though I was caught in a washing machine.

“I know you have no reason to believe me,” I said. “But I don’t work for the CIA.”

“It’s not about you,” Horowitz told me graciously. “I know you’re telling me your truth.”

Horowitz encouraged me to find out who our new shareholder is, and whether Gawker CEO Nick Denton “established his billions on the up-and-up.” I promised to consider it. We all hugged gingerly, and I immediately went to bed.

“All the speakers here are really courageous,” Susan Shumsky told me, late in the cruise, over a dinner of rubbery fish, the dining room pitching from side to side and the glassware rattling.

Shumsky has had a fascinating life: She spent 22 years on an ashram, and seven years on the personal staff of the Mahirishi Mahesh Yogi, who first led the Beatles to enlightenment, or at least to LSD, and whom John Lennon later denounced as a fraud. Since 1989, she’s been living in an RV with no fixed home base, crisscrossing the country, leading spiritual cruises, writing books, and consulting privately. She clears people’s energy fields and teaches them how to communicate with God. “Or higher beings, or your higher self,” she said. “Whatever you want to call it.” She’s a staunch, old-school feminist, who’s never married or had kids: “I enjoy my own company,” she said, smiling.

Shumsky was apologetic about Kane and Horowitz chasing the reporters around the boat, and she made it clear that she didn’t necessarily share the beliefs of every single speaker. But she believed all of them were united by their courage, and by the bad things that happened to them when they went public with their beliefs.

“They’ve stepped on a limb,” she said. “Several have been terribly smeared in the media.” The idea was to provide a place for a healthy, free exchange of ideas. “I love the camaraderie of a cruise ship.”

The next morning, Shumsky had to intervene again. Horowitz and Kane had jumped out at Litovsky and Dickey and tried to hand them a huge stack of photocopies. (These turned out to be of the junk science article and information from Wikipedia about Hearst, the magazine’s parent company.) Horowitz got very close to Dickey, trying to shove the paper in her hands. Larry Cook, an anti-vaccine activist, intervened. He and Horowitz got in a heated shoving match, with Dickey pinned up against a wall behind them.

With Shumsky’s help, Horowitz and Kane were corralled on one side of a hallway, while Dickey, Litovsky, and I were on the other. Cook stood between us and Horowitz and refused to move.

“I won’t tolerate that behavior,” he said afterwards. (He later revealed, in a low-key manner, that he’d been praying for us, and that a crowd of angels had descended on the boat for protection.)

Dickey, Litovsky, and I took Shumsky aside and told her, heatedly, that we needed to be assured that we were going to be free from harassment for the rest of the trip. As this negotiation was taking place, Wakefield appeared. He wanted the reporters to come inside the conference room and watch a presentation he was about to deliver.

We declined, having already planned as a group to attend another presentation about building “wishing machines.” Wakefield asked over and over for someone from the media to come in.

McRoberts agreed to go, but as it turned out, Wakefield had really wanted Popular Mechanics, because the first part of his new lecture was a screed against them. McRoberts, as the sole representative of the media, had the aggrieved speech delivered to him personally. He described it on Violent Metaphors, politely, as an “uncomfortable” experience.

It was a bit of a debacle, from a PR perspective. Sean David Morton and Dannion Brinkley were quietly assigned by the trip organizers to make sure the Horowitz/Kane dream team didn’t continuing hassling “the girls,” as everyone began referring to the reporters. (I was the youngest of “the girls.” I am nearly 30.)

“We got you,” Brinkley told me at dinner that night, giving me another lengthy hug. He looked at me thoughtfully and started to tell me something he’d just discerned about my future.

“You’ve got two choices,” he began. He promised to tell me the rest later. We never got around to it.

“I’m not an attorney,” Sean David Morton told us, in one of his last presentations. “I’m not a member of the British aristocratic registry. I don’t belong to the private bar association.” He was referring to a belief that “BAR” stands for “British Accredited Registry” or “British Aristocratic Registry,” and that the American Bar is secretly controlled by the Queen of England. That’s not, to the best of my knowledge, true.

Although his wording was unusual, Morton was clear with his audience that he is not licensed as an attorney. He referred to himself as an “attorney in law” as opposed to an “attorney at law,” which would be a person who went to law school, passed the bar exam and is licensed to practice law.

Morton also clarified that nothing he told anybody should be construed as legal advice, that it was all “for entertainment purposes only.” He allowed that he’s had “some successes and some mistakes,” but added, “I’ll tell you there’s paperwork you can file to establish your status as a free-living person.”

It still seemed legally perilous to me, after sitting through another hour of it. Many people aboard disagreed. One of Morton’s devotees was a gruff, friendly woman who emphatically denied me permission to use her name. I liked her very much. She told me that September 11 was an inside job, the Sandy Hook massacre was filmed on a movie set, and that the government is injecting something into the chicken sold at both Church’s and Popeye’s for mind-control purposes.

In turn, I told her, when she asked, that I thought some of the stuff we were hearing wasn’t necessarily true.

“What’s your source of information?” she scolded me. “Keep an open mind.”

She was there, she told me, to get out of debt. She’d come all this way to listen to Winston Shrout and Sean David Morton. I was actively anxious about what would happen if she went home and started showering a judge or a credit card company with garbage.

One night, we ended up in the bar together, all the reporters and her. We toasted each other’s health and I asked if she’d gotten what she came for.

“They should have said that all this is just introductory information,” she said, politely. “Then I would not have been here.”

She was hoping to grab some private time with Sean David Morton, she added, where she’d demand specifics on what she needs to free herself from the grasp of the feds.

“I know some people that this stuff is working for,” she told me, her voice dropping confidentially. “They’ve got black cards and everything. And once you reach a certain point [financially], they make you sign a nondisclosure form.”

Morton, she vowed, was going to show her what she needs to know.

That seemed worrisome. After his last lecture, I approached Morton. He was sweating heavily and looked unhappy to see me. During his presentation, he’d mentioned that one of the people he’s advising in a non-lawyer capacity is named Dennis Dale Bailey. I Googled the name and saw that Bailey is a Kansas financial adviser, charged with defrauding his clients in 2013. (The Kansas Securities Commission says Bailey pleaded guilty to fraud of over $250,000, a felony, on October 1, 2015. He is scheduled to be sentenced in late March.)

When I asked Morton if the Bailey he was advising was the same person, his wife Melissa overheard. “I told you not to use his name,” she hissed. Then she left the room.

Morton looked back at me, grimacing. We stood together in silence for a second, swaying with the motion of the boat. He sat down. I apologized for getting him in trouble, then asked about the $11 million judgment entered against him and Melissa. He maintained that the SEC’s case was bunk, and that, furthermore, he’s settled that debt by writing the court a bond for “50 million bucks,” which he argued has put the matter to rest.

“They haven’t bothered us again,” he said. “The whole deal was more of an embarrassment to them, I think.”

I still felt a little disquieted. “I worry you’re advising people to file this kind of stuff themselves,” I told him. “It seems extremely risky.”

“I’m not advising people to do that,” Morton responded, emphatically. “You have to study this stuff. I am not telling people to do this in a half-assed way on their own.”

A day later, the woman who came here to see Shrout and Morton reported back. She looked relieved: Morton has told her exactly what to do, she said, what forms to file, and she was going to do it.

“I knew he wouldn’t play me,” she said.

On our final day at sea, the media-related tensions continued. During a panel discussion, Horowitz produced his printouts again. Jeffrey Smith, the anti-GMO activist, insisted all the media leave a “strategy session” on “how to change the world.”

I was starting to feel fairly sour about all of it; it was hard not to feel as though we’d spent a week at sea either getting yelled at, chased around, or having bullshit energetically rammed into our ears. It didn’t help that the boat was steaming back towards Los Angeles from Cabo San Lucas at top speed; it was gray outside and the ship was pitching and rolling. At another early dinner, I glumly drank a ginger ale with the Popular Mechanics girls, then retired to the bathroom to vomit.

Unexpectedly, my heart softened at the very last panel, when all the presenters gathered together to tell us what we’ve learned. We were back in the windowless conference room, with every one of the characters arrayed before us; it was like the Wizard of Oz, with more tax evasion.

Sean David Morton was resplendent in a hideous silk tie, showing off a similar tie he’d just given to Dannion Brinkley. They posed together proudly. Kane and Horowitz were there, looking both defensive and in love. Susan Shumsky took a seat opposite me and smiled at me tentatively.

Morton asked everyone what what the “moral of the story” was. Wakefield and Tenpenny talked about vaccines. Horowitz and Kane delivered some jabs about the biased media. Helen Sewell, the astrologer, resplendent in a hot pink tea dress, told us about how Uranus (which she pronounces “Urine-us”) is affecting us all. She praised the bravery of her fellow speakers.

“You’re all Promethean spirits,” she said gently. “You’ve all awakened, and you’re shining your Uranian light into Pluto’s underworld.”

Nick Begich, the kind and reasonable “government is controlling the weather” guy, delivered a genuinely lovely speech, one that touched obliquely on the week’s shitstorm.

“We used to be able to break bread with people we disagreed with,” he said, “while looking for solutions together.” Change and human connection are still possible, he added, looking at no one in particular, “if you pull back long enough to recognize the human being in front of you.”

“You’re all Promethean spirits,” she said gently. “You’ve all awakened, and you’re shining your Uranian light into Pluto’s underworld.”

I thought about the anti-vaccine activists politely arguing with me about measles at dinner, or Michael Badnarik dreaming of his glorious, independent Texan republic. I thought about Larry Cook stepping in to defend us, sending down his protective order of angels. Or Horowitz and Kane, who, after they’d stopped filming and interrogating me that night, told me how they met at a conference thousands of miles from home, though both were born and raised in Philadelphia.

It’s actually very sweet, I realized, that two people with such a unique worldview found each other. They live on a beautiful estate in Hawaii now, Horowitz said, “although the bad guys are trying to take it away.”

And then, to my great delight, Winston Shrout, the other semi-legal adviser, revealed something unexpected.

“I do operate in different realms,” he told us amiably, in his Oklahoma drawl. “I set there on the galactic roundtable with Saint Germaine. We plot out what needs to be done.” Plus, he revealed, “I do quite a bit of work with fairies and elves.”

One particular “incarnate fairy,” he said, is very powerful. In 2011, he asked her to move the prime meridian. She did that, and then he filed an enormous lien “against all 12 of the Federal Reserve banks.”

Those two things, taken together, have had a tremendous impact: “At this point here, the Federal Reserve has been completely dismantled.” It hasn’t, but he got a round of applause anyway.

Shrout said that he and a team of galactic warriors are almost done making the “major corrections” needed in the universe, including plugging up a black hole that’s been interfering with some financial issues.

“We expect great things certainly by the Chinese New Year,” he told us.

The moral of the story is this, Shrout added: “When all the corrections have been made and the systems are functioning properly, when you have the opportunity to be free, what will you do?”

A lot of people in the room, he said, “have been at war so long, that’s all we know. All we know is conflict. But shortly, it will stop. So what will you do to honor the peace?”

I suddenly felt wonderfully lucky, that all of us could be here together, getting in touch with the furthest reaches of what anyone can believe.

And who’s to say, anyway, what’s true and what is bullshit? Somehow, after a week on the boat, the notion of truth seemed remote. I walked outside, into the soothing darkness, where the ocean was surging against the sides of the ship. I stood there for awhile, staring at the rolling, vast blue-black water, its mysteries all safely hidden below the surface.

Hours after we disembarked from the cruise, both Morton and and his wife Melissa were arrested. They were charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States by filing false tax returns with the IRS, and by submitting what an indictment calls “fictitious financial instruments” as a means of paying off debt, including to the IRS, numerous banks, and the California Franchise Tax Board.

“Driven by insatiable greed and a blatant disregard for the tax code, Mr. and Mrs. Morton have a long history of allegedly filing bogus tax returns and fictitious instruments claiming fraudulent refunds,” Erick Martinez, special agent in charge of the IRS Criminal Investigation unit, said in a statement.

If convicted, each faces a maximum of more than 600 years in prison.

Update, March 2, 2016:

In an email, Susan Shumsky disputes that Sean David Morton was involved in organizing the Conspira Sea:

Sean David Morton announced to the group on the ship that “we” decided to organize the cruise after last year’s conspiracy panel at the Conscious Life Expo in Los Angeles. I NEVER said that, because it is NOT TRUE. The Conspiracy Cruise was entirely my idea and my invention. Sean was NOT a co-producer and NOT a cruise organizer in any sense of the word. It was NOT his idea. I did not correct Sean in public, because I would not embarrass anyone in that way. So, when he gave himself credit for conceiving the event, I just let it slide and I said nothing. I DID NOT give Sean credit in front of any audience. He gave himself credit and I remained silent. I was being polite. I NEVER gave Sean credit. He did.

Shumsky adds that Morton’s only contribution was suggesting Shrout as a speaker. She says, too, that she was unaware of “Sean’s problem with the IRS,” adding it has “ABSOLUTELY NOTHING to do with me, and ABSOLUTELY NOTHING to do with the cruise.”

She concludes: “BTW, all the people who filled out and returned the evaluation forms for the Conspira-Sea Cruise had a wonderful time, and all the comments I received were extremely positive. So the participants loved the Cruise.”

Correction: An earlier version of this post identified Laura Eisenhower as President Dwight Eisenhower’s granddaughter; she is his great-granddaughter.

Illustrations by Jim Cooke.

Contact the author at [email protected].

Public PGP key

PGP fingerprint: 67B5 5767 9D6F 652E 8EFD 76F5 3CF0 DAF2 79E5 1FB6

GET JEZEBEL RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Still here. Still without airbrushing. Still with teeth.