Illustration: Jim Cooke, Photo: Getty

According to the New York Times’s Kathleen Kingsbury, we are living in a period of political division. In June, the newspaper published an op-ed by Tom Cotton, sparking weeks of debate over the politics and practices of mainstream media. Looking for a silver lining in the fallout over Cotton’s racist screed, Kingsbury, recently appointed the acting opinion editor at the Times, wrote that it “generated a necessary dialogue” and “elevated a conversation worth having and will help inform what discourse looks like in a polarized world.”

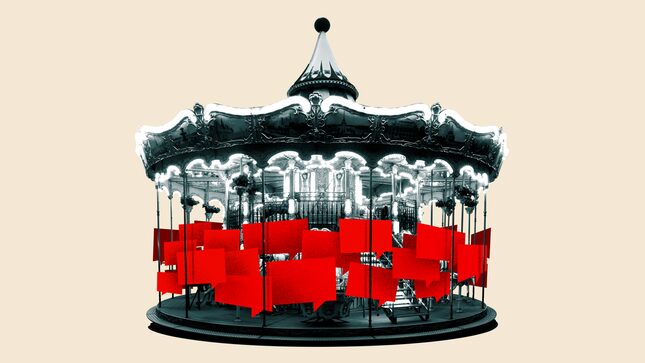

Kingsbury’s proposed solution to the polarization she identified—namely, conversation—is telling. The claim felt pointed, particularly now as establishment media and political personalities are concerned about the consequences of radical demands for systemic reinvention, restructuring, and abolition in the wake of the covid-19 crisis and the Black Lives Matter movement. This is neither accidental nor benign. It is the deliberate project of what I call the Having Conversations Industrial Complex: a loose assemblage of professional speakers, non-profit organizations, astroturfed activists, diversity consultants, academic advisory boards, panelists, and politicians who are paid to generate a “conversation” that doesn’t need to show tangible results. Rather, the only role of the conversation is to generate more conversations. And while they profit off of the Having Conversations Industrial Complex (professionally, socially, financially, and ideologically), those at the frontline are injured, arrested, and labeled “terrorists.” The Having Conversations Industrial Complex exists to enrich the powerful and defuse radical demands.

From Google to Target, to Tim Hortons, to L’Oréal Paris, to Coca-Cola, to Spotify, even corporations are having conversations. In the lingo of the Having Conversations Industrial Complex, companies are “listening,” “learning,” and striving to “do better,” without doing much beyond posting a black square or a vague statement about racial justice on social media. But brands are not the only ones “having conversations” right now. Educational institutions that spent the last several decades harming and policing students and faculty of color are suddenly recommitting to “diversity” and “dialogue,” absent any material, structural changes. School boards are ostensibly ready to learn about the dangers of racism, even as they’ve been ignoring evidence of racism for years. Even police departments are “listening” as well. Politicians are excited to have conversations, too, so long as those conversations don’t require them to take a stance. The conversation is continuing, with no end in sight.

Protesters have been very clear in calling for police defunding; prison abolition; direct investment in an autonomous Black community; and justice for the victims of police murder. By all measures (and with few, token exceptions), none of these demands have been met, or even taken seriously by those in power. Campaign Zero’s much-lauded “8 Can’t Wait,” a favorite among political glad-handers, has been roundly debunked and rejected as ineffective and unscientific. Though activists countered with a more progressive plan in “8 to Abolition,” it was Campaign Zero’s that was boosted by recognizable names like Ariana Grande and Oprah. In many cases, successful changes came as the result of one week of uprisings after organizers spent long, fruitless years working within the system. In a familiar song and dance, city councils like those in Toronto proposed yet another round of reforms, reviews, and audits, rather than listening to Black and Indigenous activists or following through on policy changes. Having conversations doesn’t seem to be doing much other than generating contracts, draining energy, and stalling significant action.

The Having Conversations Industrial Complex is essential to the workings of liberal political culture. It occupies the nebulous middle-ground between good intentions, institutional inertia, and wholesale repression. Its members are generally salaried, well-connected, appointed, or closely affiliated with a wealthy institution. It includes celebrities like JK Rowling and Killer Mike, who pose as community leaders; university administrations and their machiavellian asset management corporations; bourgeois editors and pundits; diversity and equity professionals like Robin DiAngelo; politicians and lobbyists; nonprofit corporations like the Anti-Defamation League who have used their authority to attack numerous vulnerable groups; and public relations teams, who help manage reputations employing the rhetoric of social justice. They push people and projects through a revolving door of empty promises, acting as agents of reformism, the political belief in incremental change rather than abolition or the development of alternative systems.

Any social issue—from racism, sexual harassment, state surveillance, apartheid, inflated police budgets, the militarization of the public sphere, or the invasion of indigenous land—is greeted with a call for necessary conversation. And if it seems like these conversations are unending and fruitless, that is because they are; so long as conversations continue, those who facilitate them benefit, and the status quo remains functionally intact. The motivation is painfully banal: Having conversations is just the ordinary outcome of doing politics under liberal capitalism. Put simply, the employees, investors, stakeholders, and leaders of various businesses, bureaus, and nonprofits have a vested interest in staying paid, relevant, and close to power. In the end, they’re all just doing their jobs, and that means preserving an oppressive status quo.

Think of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for example, or the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. Both of these efforts were celebrated as important first steps, but they were quickly diluted and dismissed by the media, government, and the nonprofit sector the moment they challenged the colonial-commercial interests of the Canadian state. A similar process of having conversations defined the lead-up to the construction of the undeniably colonial Dakota Access Pipeline in the form of staged, constrained consultations with various stakeholders as part of a rubber stamp-style consultation process. Then there are the many official and unofficial reports and book deals spawned in the wake of the disastrous American invasion of Iraq, itself the product of misinformation disguised as consultation and investigation. Though several think tanks and security consultants have supposedly learned the “lessons” of the Iraq war, its key American perpetrators remain unpunished, troops remain on the ground, and the United States has yet to offer reparations to the Iraqi people.

In this way, the machinery of knowledge production, public speaking, and officially-defined accountability works to allow the systems that reproduce and profit from exploitation to appear magnanimous (perhaps even non-discriminatory) while still maintaining the familiar order. It enables those in power to feign accountability and transparency, without motivating action or material change.

The popular fixation on having conversations works precisely by playing on a facade of good-natured neutrality that simply does not match up with the material actions of powerful institutions. The Having Conversations Industrial Complex makes simple demands look difficult, obvious solutions appear impossible, and conflates business interests with community needs. It encourages tokenism and essentialism in the form of caucuses, vetoes, and running mates, rather than material social, economic, or political change. Politicians can have conversations about LGBTQ issues, for example, while continuing to criminalize and endanger sex workers. This toxic logic of representation is how we end up with Pride parades that include LGBTQ police officers; it allows institutions to escape criticism through gestures of representation or “visibility.”

Having conversations obscures the insidious creep of what the Palestine movement terms normalization, the practice by which an intolerable state of affairs becomes business as usual, by treating structures of violence as partners in search of solutions. For those of us who do not have the luxury of being non-representative, participating in these conversations allows institutions to redirect dissent into advantageous, disposable, ineffectual, or legally toothless channels. At best, it’s a mechanism of “manufactured endorsement,” a sleight-of-hand using the appearance of community consultations to claim consent; at worst, it is a form of surveillance.

It’s hard to escape the Having Conversations Industrial Complex, but some have tried. In Palestine, decades of normalization and empty words compelled a popular demand for a boycott; Palestinian activists refused to continue participating in fruitless negotiations and opted to boycott Israeli products, calling on international allies to do the same. In Canada, Indigenous activists used a similar tactic earlier this year by refusing to accept Canadian state pacification and deflection; they blockaded key rail lines across the country, proclaiming the death of “Reconciliation” and demanding an end to “negotiation at the barrel of a gun.” And over the last month, Black people in both the United States and abroad rose up against state violence and liberal reformism, demanding abolition through coordinated riots and mass demonstrations.

Still, the Having Conversations Industrial Complex has continued to try and offset the impact of these actions, but the lesson is clear: we can, and should, recognize that having conversations cannot provide solutions. In nearly every case, the response from the state has been to label BLM and similarly radical movements as “terrorists,” to criminalize them, and subject them to repression and violence, akin to what Cotton called for in the Times. Even now, countless police departments are doing the same to Black people across the continent.

It is no longer sustainable to play softball with a state that wants to see large swathes of its population dead, whether that death comes quickly at the hands of the police, or over a matter of months or years through exploitation and deprivation. The same institutions that demand compromise and collaboration have been profiting off of persecution and repression for generations, buoyed by a threat of violence and incarceration. Refusing to participate may earn us the label of “terrorists” in the eyes of the state, and it may see participants chastised by those who work within the Having Conversations Industrial Complex. But it produces real results, and it frees us from being trapped in a cycle of fear and loss. It allows us to conserve our energy, allocate our resources, and uplift true community leaders rather than those who would sell out to the first corporation or politician to come by. As long as we cede to having conversations, genuine material redress can never be possible.

There is no need for conversation, only justice.

Alex V Green is a writer based in Tkaronto. Their work has been published in Buzzfeed, Jewish Currents, Outline, Xtra, and Slate, among others. You can follow Alex on Twitter @degendering, or at their website alexverman.com.

GET JEZEBEL RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Still here. Still without airbrushing. Still with teeth.