A Kansas City Cop Sexually Assaulted ‘Countless’ Black Women and Girls, None of Whom Can Sue Him

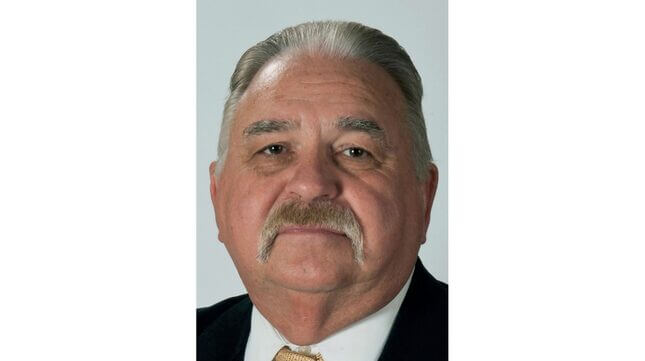

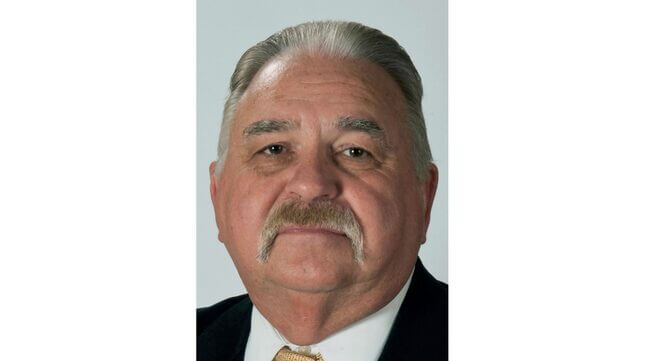

Longtime police detective Roger Golubski sexually victimized more than 70 predominantly Black and poor women, but state law prohibits them from seeking justice.

In Depth

Two women who were repeatedly sexually assaulted by a retired Kansas City detective aren’t able to pursue legal claims against him, as the state’s statute of limitations on sexual assault—10 years after the assault—has expired. Now, in a horrifying feature published by the Kansas City Star, the women are telling their respective stories about Roger Golubski. Naturally, Golubski has quite the record of criminal allegations—particularly as they pertain to Black women and poor and working-class people.

The women’s stories were first made public via a lawsuit filed by Lamonte McIntyre, who alleged Golubski framed him in a 1994 double murder case. McIntyre has since been exonerated. In court records, his attorneys claimed that throughout Golubski’s career, the detective had “victimized, assaulted, harassed” or intended to harm more than 70 women in Kansas City. Golubski, they alleged, used his badge to victimize “countless” vulnerable women—a number of them homeless, addicted to drugs or sex workers—often exploiting them for sex or to act as “informants” in cases he was working on. Most women named in the suit used only their initials.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-