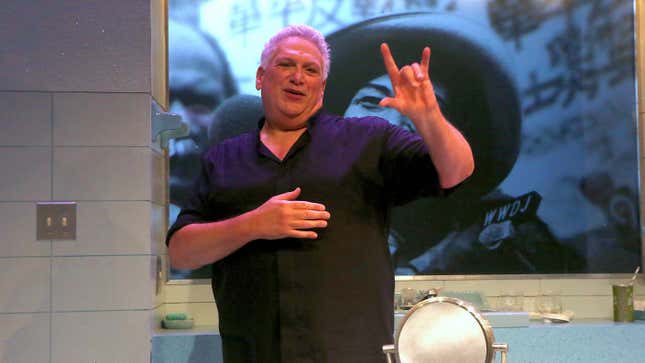

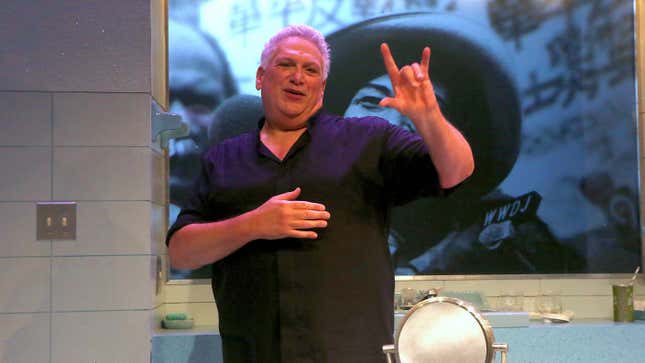

Who Is Harvey Fierstein? His Memoir Only Begins to Explore an Answer.

The out Broadway legend discussed Barbara Walters, PrEP skepticism, and lingering questions of identity upon the release of "I Was Better Last Night."

BooksEntertainment

“Who the fuck are you and why am I looking at your ceiling?” boomed a voice, as smooth as glass in a blender, through my computer speakers a few weeks ago. It was that of playwright/actor Harvey Fierstein, and the occasion was a discussion about his new memoir, I Was Better Last Night, out Tuesday. There’s hardly a good answer to the question, “Who the fuck are you?” when someone with a resume like Fierstein’s asks, so I didn’t even try. I did, however, adjust the angle of my laptop’s cam.

I thought I knew who Fierstein was. I’d spent the better part of a week inside of his head via his extensive memoir, which is a vivid and wry trip through his life, as only he could tell it. To say his voice is singular is to acknowledge his distinctive timbre (he’s perpetually hoarse, as if always recovering from yelling the night before, which he says is the product of enlarged secondary vocal cords), as well as his unique vantage point as one of the earliest (and most matter-of-fact) out gay celebrities. He wrote and starred in, as he puts it, Broadway’s “first openly gay play with an openly gay lead,” Torch Song Trilogy, which debuted in 1982 and ran for more than 1,000 performances. In 1994, he became the first openly gay actor to play an openly gay role in a sitcom via CBS’s short-lived Daddy’s Girls. The 69-year-old has spent much of his career in drag, starting in the ‘60s in La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, where he acted alongside Warhol Factory staples Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Holly Woodlawn. In 2003, he won a Tony for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical for his work as Edna Turnblad in the Broadway production of Hairspray. He memorably helped Robin Williams’s character transform in a supporting role in Mrs. Doubtfire.

In the book, as on Zoom, Fierstein alternates between earnestness and sarcasm. I knew this going in, so when he told me, “Fuck you!” within the first 10 minutes of our hourlong conversation, I took it as a compliment—a sign that he was comfortable enough to joke around with me. I did not get the sense that he meant offense or was offended at the question that prompted his profane retort: whether or not he worked with a ghostwriter on his memoir. He emphatically did not. “I mean, I write op-ed pieces, and my shows are actually good,” he submitted as evidence. “They’re actually well-written. I have like six Tony Awards. I must know how to type or something.” (Fierstein, per his Wikipedia, has four Tonys, but point taken. He definitely had the most Tony Awards out of everyone on our Zoom.)

A few minutes later, when I referenced the book’s oodles of Harvey-isms (“Guilt is stronger than instinct;” “Time heals nothing;” “The ‘60s happened mostly in the imagination;” “Prejudice is art’s greatest enemy”), he returned, “They wouldn’t be Harvey-isms if somebody else wrote them!” Later still, he referenced my question again after a philosophical monologue (hardly the only one he delivered) regarding what he views as an oft-spoke fallacy: that all humans are the same.

“From childhood, I was taught we’re all the same. And the truth is we’re not the same at all. We’re all completely and utterly different,” he said. “I will accept you for what you are, and you accept me, instead of this bullshit of, ‘We’re all the same.’ It hasn’t worked so far, and I just think it’s the wrong message.”

He paused as if to reflect and then continued, “Now the world will say, ‘Who wrote that for me?’” He added with a smile, “I’m not letting you get away with that.” Okay, okay! I believe him.

The dog by Fierstein’s feet was as close as he got to a co-writer while he worked on his book through the pandemic. When it hit in 2020 and he was locked down at his home in “a small fictional town in Connecticut,” he cleaned his desk, polished off some quilts he owed people (he sews them in his spare time), and then took the suggestion from his agent to get started on his life story. His friend Shirley MacLaine gave him this advice: “Let your memory guide you even when you’re writing about someone else.” What went in and stayed out was largely determined by his gut.

From childhood, I was taught we’re all the same. And the truth is we’re not the same at all. We’re all completely and utterly different.

I Was Better Last Night is not a particularly gossipy book. For example, Fierstein tells the story of an actor who treated him like shit during one production only to apologize at the end for picking on him—to help ease daddy issues, she explained, she targeted a male castmate during every show and laid into him. It just happened to be Fierstein’s turn. He declines to name her in the book and reasoned during the interview that it wouldn’t do much good. “Do I have terrible things to say about people? Absofuckinglutely,” he said. “Does it belong in a book? And what good is it going to do anybody?”

Granted, he can be acerbic about the bold names he’s rubbed elbows with. For example:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-