Maximalism Is Back

In Depth

Minimalism—as a lifestyle and an aesthetic—is on its way out. Buoyed by the enduring popularity of mid-century modern design, minimalist and minimalist-adjacent interiors are so ubiquitous that seemingly every public space, be it a doctor’s office, a women’s coworking space, or a bougie Vietnamese restaurant offering still or sparkling water, looks predictably, exactly the same.

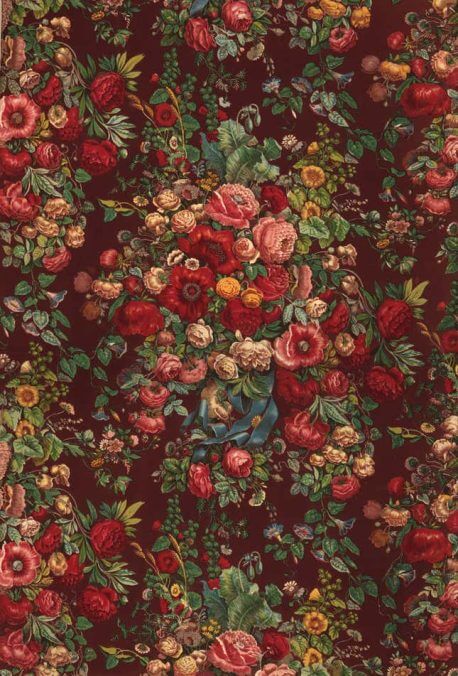

Right in time for a coronavirus-induced retreat indoors, the pendulum is swinging from minimalism to maximalism: the compulsion to burrow, to nest, and to decorate our homes like magpies, as a means of insulation against anxiety and stress. Consider maximalism the louder, happier, brighter and cozier cousin of minimalism—a flight to domesticity in the face of uncertain times.

The reaction against minimalism is less of a conflagration than a slow burn, a gradual realization that while minimalism’s promise was to soothe, via calm, uncluttered interiors and white walls, within its pristine interior, status anxiety flourished. Sure, at its outset, minimalism was a reaction to the consumerist impulse towards purchasing unnecessary items to fill a void. But as Chelsea Fagan outlined minimalism’s failures in the Guardian in 2016: “It is just another form of conspicuous consumption, a way of saying to the world: ‘Look at me! Look at all of the things I have refused to buy, and the incredibly-expensive, sparse items I have deemed worthy instead!’”

And so the pendulum swings the other way, now, towards a more ebullient aesthetic: It’s no wonder that Memphis design briefly emerged in 2018 as a respite to grey sofas and concrete floors. With its cheery, bubbly shapes and colors, reminiscent of the lobby of an upscale Holiday Inn, Memphis design emerged as a move away from Scandi design’s dominance and towards something a little more dynamic and expressive. But the rise of cottagecore, an aesthetic with roots on Tumblr that leans heavily on bucolic garden scenes, teapots and doilies, suggests another, increasingly urgent directive: consider maximalism, instead.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-