Not Only Do Campus Sexual Assailants Go Unpunished, They Often Get Special Treatment

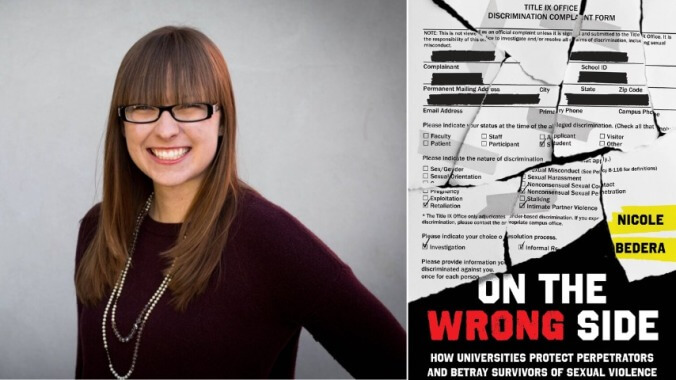

“If you treat victim and perpetrator the same, you will always be enabling the perpetrator," Nicole Bedera, author of On the Wrong Side: How Universities Protect Perpetrators and Betray Survivors of Sexual Violence, tells Jezebel of her year observing Title IX cases.

Photo: Eros Hoagland/Getty Images In Depth

Nicole Bedera met and interviewed “Justin” and “Marissa” a year after their Title IX case closed at the university they attended. Both were participants in Greek life, and even though Marissa reported Justin for rape and Justin denied the allegation, their narratives about what happened were nearly identical. They both agreed Marissa had said she didn’t want to have sexual intercourse. They both agreed that Justin penetrated her later in the night despite this. They both agreed that Justin became violent with her, hitting her with his belt and choking her. (Justin characterized this to administrators as being “kinky.”)

The Title IX office sided with Justin, seemingly from the get-go.

Justin’s “proof” of consent was that he and Marissa discussed her birth control method and their last STI tests, and Marissa removed her clothing and consensually engaged in some sex acts with him. He also pointed to her responses to his texts the next day saying she enjoyed their night together. On her end, Marissa recounted repeatedly asking Justin to stop during their encounter. She recalled eventually performing the sex acts he wanted because she feared for her life as he became increasingly violent, and said she continued to respond to his advances over text because she remained fearful for her safety. This, Bedera told Jezebel, is a common trauma response among victims known as “fawning,” as victims feel compelled to flatter and appease their assailant out of fear. But there’s no requirement for Title IX administrators to have backgrounds in sexual assault research or working with victims, and consequently, few understand these complexities.

Justin and Marissa’s story is told in detail in Bedera’s new book, On the Wrong Side: How Universities Protect Perpetrators and Betray Survivors of Sexual Violence, for which she spent a year observing the Title IX office of a large public university (which she calls Western University) and conducting 76 interviews with Title IX administrators and students. In the book, Bedera dispels deeply ingrained campus rape myths and puts the innate violence of the campus sexual assault reporting process into focus. “There’s this myth that men’s lives are ruined when they’re accused of sexual violence—it isn’t just untrue, it becomes the justification for giving them benefits to compensate for that notion,” Bedera said.

On the Wrong Side features over a dozen case studies, and presents an unsettling conclusion: Not only do assailants often go unscathed by Title IX reports, but they also reap academic, professional, and social benefits, Bedera found. “There was this pervasive thinking of, ‘I don’t want people to think I’m unfair to the perpetrator, so I’m going to go above and beyond to treat them better than anybody else,’ so there can be no allegations of bias,” she said.

“There’s this myth that men’s lives are ruined when they’re accused of sexual violence—it isn’t just untrue, it becomes the justification for giving them benefits to compensate for that notion.”

Western University’s Title IX office received close to 500 reports during Bedera’s year at the university. Of those reports, a student was suspended or expelled just 1% of the time. The university suspends 3.29 students per year for gender-based violence; it expels just 0.71 students. (The only perpetrator who was expelled the year Bedera was there was expelled for threatening physical harm against a Title IX administrator, not the victim.) This is just the case of one university, but in her introduction, Bedera writes that students from schools across the country have asked her if Western University is their school—that’s how universal its Title IX office’s mistreatment of students is.

Between the last three U.S. presidents, guidelines for how universities that receive public funding handle campus sexual assault reports have fluctuated. But no matter who’s in the White House, Bedera writes that universities can often manipulate the ambiguity and toothlessness of federal policies to take little—or, more often, zero—action in response to reports. Approximately one in four women undergraduates is victimized by sexual assault—an act perpetrated by one in 10 male college students, according to one study. But universities suspend just one of every 12,400 students each year for sexual misconduct offenses and expel one in 22,900.

‘Himpathy’ and neutrality

On the Wrong Side presents two terms that are fundamental to understanding university malpractice on campus sexual assault. “Institutional betrayal” describes the trauma that survivors experience when their university’s action or inaction creates new harm, compounding the trauma of sexual assault. Survivors of institutional betrayal, Bedera writes, “report traumatic symptoms similar to those of victims who were raped twice.” Another term Bedera introduces us to is “himpathy”—excessive, gendered sympathy for men at the expense of women. If a male student punches another male student, he could be immediately expelled; if a female student reports a male student for assault, he’s often perceived as her victim. “Himpathy” justifies benefits that perpetrators reap solely for being accused.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-