Rethinking the Film Canon

Generally speaking, the canon filled with the usual suspects (Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, The Godfather, Citizen Kane).

EntertainmentMovies

Image: AP

In interviews, director Spike Lee often tells the story of the miseducation (or an attempt at one) that he received during his first year of graduate film school at NYU about the 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation. “They taught that [Nation director] D.W. Griffith is the father of the cinema,” he has recalled. “They talk about all the ‘innovations’—which he did. But they never really talked about the implications of Birth of a Nation, never really talked about how the film was used as a recruiting tool for the KKK.” He rebuked Nation’s racism directly in his freshman film project, The Answer, and it nearly got him kicked out of the school.

Nation, certainly, was trailblazing in its approach to long-form filmmaking during the medium’s infancy. Griffith helped invent film’s language, including the concept of parallel editing. Nonetheless, Lee’s professors’ focus on the film’s form and disregard of its politics—which portrays Black men (many played by white men in blackface) as savage threats to the sanctity of white womanhood and the Ku Klux Klan as a necessary corrective—bespeaks reverence to a “classic,” a film whose importance as art was allowed to supersede its content and real-life effects. According to Lee and several experts, the film inspired a Klan renaissance that led to lynchings. (If there is any question as to the power of representation in pop culture, Nation suggests it was already answered at the dawn of the movie industry.)

Nation, you see, is canon, and canon is shorthand for institutionalized excellence. The film canon is roughly comprised of works widely recognized as important and being of high quality, as determined by organizations like the Academy of Arts and Sciences (responsible for the Oscars) and the American Film Institute. Other potential canon-building factors include critics (as contributors to list-publishing periodicals as well as their own consensus-forming mass), universities, distributors, and even audience consensus (measured most reliably by a film’s box office).

Generally speaking, the canon filled with the usual suspects (Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, The Godfather, Citizen Kane). There are canons within the canon (Black film) and canons within canons (Black queer film), but when I talk about the canon here, I’m talking about the supposedly unimpeachable classics that most people in the United States with a working knowledge of film have seen or are at least aware of. It’s a bit of a difficult thing to nail down and discuss with absolute precision partly because it’s based on a necessarily subjective rubric (even when voted on by a committee) and is prone to reconfiguration, albeit slight. Canon like a bag blowing in the wind, letting in and out air, shifting and contorting slightly, while retaining its general shape.

Canon… seeks to recognize supremacy in film, and the vast majority of the filmmakers within are white.

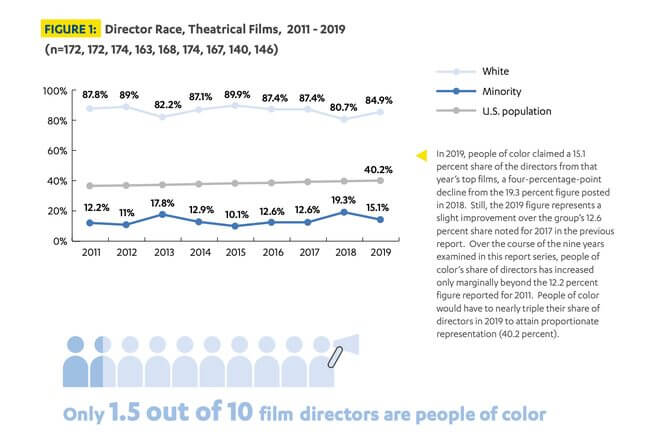

Rarely is that which has been let into the canon, though, work made by people who aren’t straight white men. The correlation between greatness in film and the creativity of straight white men is so strong that one could easily infer the gatekeepers are in fact arguing for causality. In this time of monument demolition and the rigorous reconsideration of orthodoxy, here is a way of thinking about the way that the film canon upholds white supremacy: It seeks to recognize supremacy in film, and the vast majority of the filmmakers within are white. It’s that simple.

“The issue is systemic,” said Andrew Ahn, who directed 2016’s acclaimed Spa Night and this year’s Driveways. “You have an industry, created from a country, from a world that is racist. It reveals itself in the work. There’s an opportunity to correct that now that there’s an awareness of it, in a way that I don’t think people were wise to even 10 years ago.”

Time does change things. When streaming platform HBO Max announced a few weeks ago that it was taking down Gone with the Wind, it raised the hackles of the right, with perhaps Megyn “Santa Claus Is White” Kelly shouting the loudest (at least, as loud as tweets can be) about censorship. The streaming platform, though, announced it will be putting the movie back up with a new introduction by cinema professor and TV host Jacqueline Stewart to frame the movie with proper historical context. Context is crucial, as it chips away at the notion that “classic” status renders a film beyond critique.

Institutions that help determine canon are, unsurprisingly, predominantly white. While Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden is Black, the members of the National Film Preservation Board that she heads are vastly white. The National Film Preservation Board is responsible for the National Film Registry, an annually updated list of films “selected because of their cultural, historic and aesthetic importance to the nation’s film heritage.” Meanwhile, in July 2019, a piece on the Academy that ran in the New York Times announced in its headline that “Minorities Make Up Nearly a Third of New Oscar Voters.” However, the reporting betrayed the story’s titular hopefulness:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-