Squid Game Relishes the Bleak Fatalism of Debt

Squid Game is billed as "dystopian," but its resonance is universal

EntertainmentTV

Spoilers for Squid Game ahead.

The question of how far some people would go to free themselves of debt is at the heart of Squid Game, a breakthrough hit for Netflix that is poised to be the platform’s most popular show in its history. Directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk, the South Korean import is a diabolical, original parable about money and debt—specifically, what the average person is willing to sacrifice in order to earn enough to live a life free from financial obligations—and is, unsurprisingly, resonating with viewers globally.

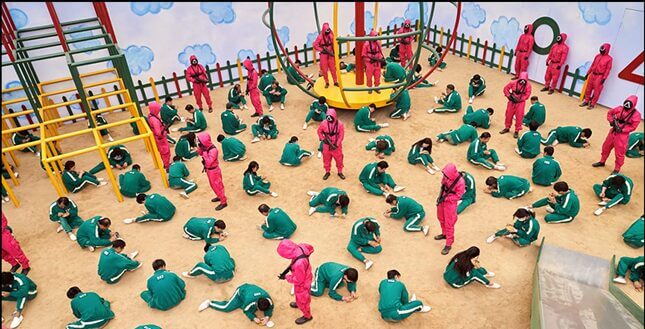

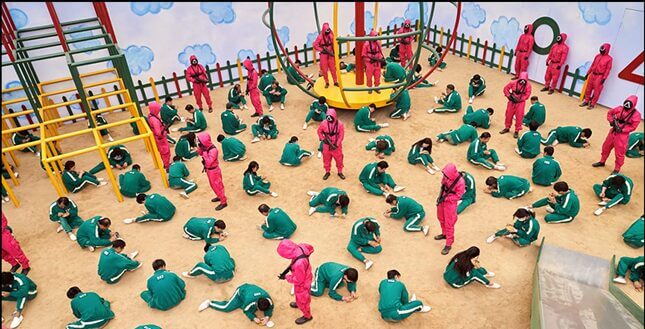

Squid Game is a broad critique of capitalism, but it’s largely about how hopelessness in the face of debt translates to real-life decisions and actions. In the show, hundreds of people crippled by personal debt make the decision to participate in a series of childhood games in exchange for a cash prize—$45.6 billion won or roughly $38 million dollars—which accumulates in a glowing gold orb suspended over the contestant’s shared barracks, the metaphorical carrot dangling in front of their eyes. The rules are simple: Play the games to advance to the next round. If you lose, you die, executed by a sniper or at close range by a team of silent masked Managers, dressed in pink jumpsuits, executing orders like Stormtroopers.

At the center of the game is Seong Gi-Hun (Lee Jung-jae), a divorced man saddled with gambling debt who is struggling to pay back his loan sharks to maintain a relationship with his daughter and provide for his ailing mother. Along with 455 other people desperate enough to risk their lives for the chance at financial solvency, Gi-Hun joins a motley cast of characters, all with different motivations: Cho Sang-Woo (Park Hae-soo), Gi-Hun’s childhood friend, has a successful career but is wanted by the police for stealing money from his clients; Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) is a North Korean defector who needs the money to extract the rest of her family; Abdul Ali (Anupam Tripathi) is a Pakistani immigrant who needs the money to support his family because he hasn’t been paid in months; and Oh Il-Nam (O Yeong-su) is an elderly man with a brain tumor who is in the game only because waiting for death inside its walls is preferable to doing so in the real world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-