In South Korea, ‘Lookism’ Is ‘Enforced With Open Discrimination’

When she was posted to Seoul, journalist Elise Hu was bowled over by the beauty industry's dominance—and impossible-to-escape standards.

BooksEntertainment

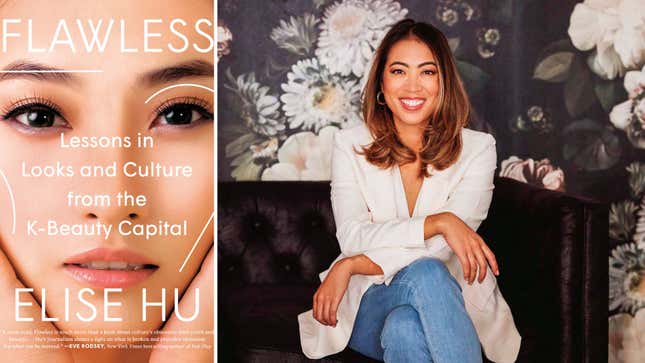

The following is an excerpt from Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital by Elise Hu, which came out on Tuesday. You can buy it at Bookshop and Amazon.

In retrospect, I began to understand the monumental labor of appearance work while I was in labor. Surely, there was air-conditioning in that birthing suite, but I couldn’t feel it anymore at the pushing stage. The sun had come down, sending long shadows into the room. My hair dripped with sweat. I wanted all my clothes off and stripped down to only my bra, out of a primal instinct to be naked. But the midwife kept covering me up with a blanket. Modesty in the delivery room?! No one was there besides the midwife, my husband, and eventually my ob-gyn, who had seen about 80,000 vaginas by then, given his line of work. I’d toss off the blanket the midwife draped over my lower half; she’d cover me back up. This back-and-forth continued a few times, even as I could feel the excruciating pressure of a small human emerging from between my legs. Finally in desperation I shouted, “Stop covering me up!” And she relented.

Later, I would come to see that unpleasant standoff as emblematic of a prevailing attitude about women’s bodies: that in their most “natural” state, when bodies are naked and not prettified, they should be hidden. The idea that femininity should be cultivated and our bodies somehow cleaned up for presentation is something I’d already been picking up from Korean beauty culture. But our bodies at their most naked can already come with confusion or shame. Having to wage a battle to be naked during an experience shared by women across time and space? It registered as wrong, even as I winced and wailed through the last few moments of labor.

In the weeks and months after we brought Isa home, I learned to censor my postpartum body. Isa’s early summer birth meant that during the first few months of her life, my skin beaded with sweat every time I stepped from the steaminess outside onto the air-conditioned subway. The extra heat that comes with nonstop lactation didn’t help. One September morning I let myself don a sleeveless V-neck dress as I took Eva to school via subway. It proved to be a quick and demeaning lesson on how not to appear in public. My nursing breasts meant I was naturally bustier, and the dress revealed a hint of cleavage. (Though not much—even my nursing breasts don’t fill more than a B cup.) I remember stepping onto a subway car and finding a spot standing next to the metal pole near the doors. But between that stop and the next one, the subway car’s entire middle area had cleared away from me. Those in the seats along the sides shot me looks of disapproval and puzzled disdain. People had moved so far away from my modest cleavage that I might as well have been loudly farting on the subway. Or naked.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-