Gentleman Jack's Sally Wainwright and Suranne Jones on Costume Dramas and Anne Lister's Diaries

Entertainment

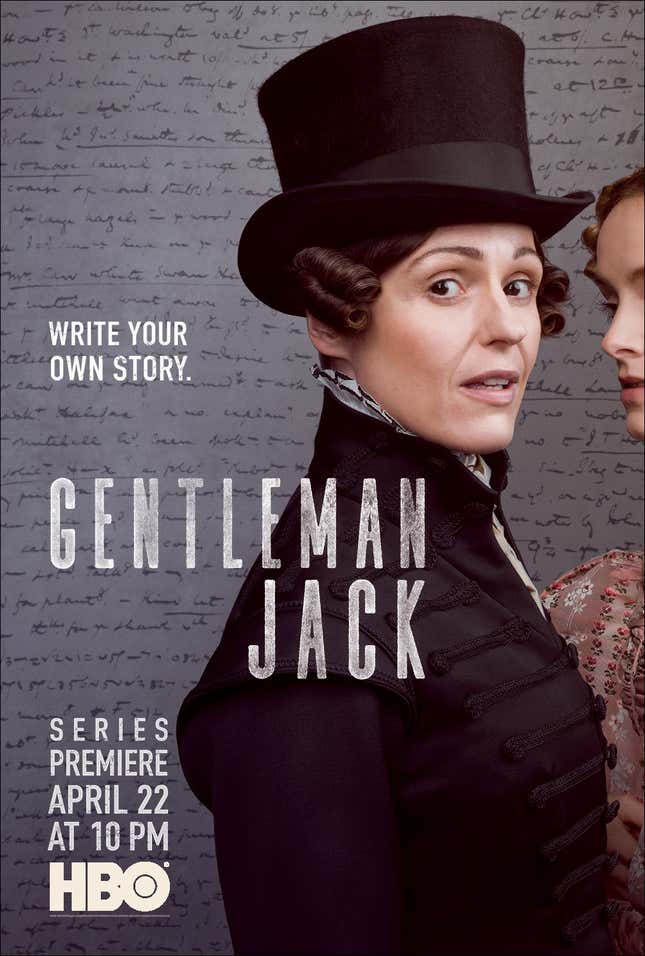

Image: HBO

It’s the plot of innumerable Regency romances: Somebody with big ambitions and insufficient fortunes decides their best move is hustling an heiress to the altar, only to catch feelings. It is also, essentially, the plot of Gentleman Jack, HBO’s entertaining new series following the adventures of Anne Lister.

Lister was a rare 19th Century woman who owned land outright and cut through all the formal and informal social mechanisms to keep gentry women at home serving tea. She recorded numerous love affairs with women in coded diaries that near miraculously survived through to the late 20th Century, offering incredible detail for potential adapters of Lister’s life. It’s hard to imagine a more compelling character.

Sally Wainwright, the creator of Happy Valley and Last Tango in Halifax, has wanted to adapt the story for decades, and has finally had the chance with Gentleman Jack. Suranne Jones plays Lister with absolutely crush-inducing swagger. Another standout is Gemma Whelan, whom you’ll likely recognize from her role as Yara Greyjoy, playing Lister’s peevish sister, so totally opposite from her Game of Thrones character that it’s an ongoing source of comedy.

I spoke with Wainwright and Jones at HBO’s New York offices recently, and we discussed Lister, her diaries, her world, and why the protagonists loll around on the couch, like they’re eating popcorn.

JEZEBEL: You’ve been on this story for a really long time, and you’ve wanted to do it for many, many years. What about it got in your head and stayed there until you finally got the chance to do it?

Sally Wainwright: Just the sheer force and eccentricity and brilliance of her character. I think she’s a really uplifting human being, and I think that’s the top and bottom of it. It’s just this extraordinary woman who did these extraordinary things and who lived this extraordinary life—and wrote it all down. That’s the most extraordinary thing of all, about Anne Lister—the volume of this diary, you can’t underestimate. People don’t get how big it is. It’s 27 volumes, 300 pages in every volume, it’s very tiny writing, a sixth of it is in code. The books that have been published cover a fraction of it. There’s a significant amount out there, but even that is only a fraction of what’s actually been transcribed and published.

So, it’s her. She’s a very, very compelling woman.

How do you begin, when you have that much material—we all know the problem of having all this research and you want to put every last detail in and you have to carve it down into a watchable TV show. How did you go about shaping the material and figuring out what the through line was?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-