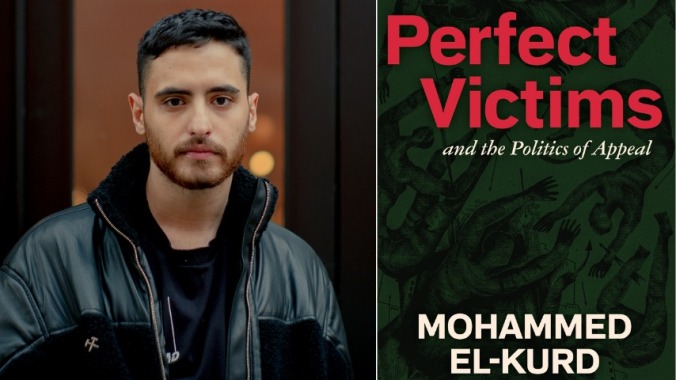

‘On Trial for Crimes Committed Against You’: Mohammed El-Kurd on Palestine and ‘Perfect Victims’

“Even if the worst you say about me is true, you have no right to steal my land, oppress me, erase me,” the writer told Jezebel of life under Israeli apartheid.

BooksEntertainment

Palestinian writer Mohammed El-Kurd remembers when, as a child, journalists would visit his home in Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem, as settlers from Israel and the U.S. increasingly displaced families like his. In his new book, Perfect Victims, he writes about the journalists’ interest in documenting his community’s suffering, sometimes interviewing children like him. But they weren’t interested in Palestinians’ political analysis about their own oppression—the “conflict,” as the decades-long ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their land is often gently labeled, was supposedly too complicated for the people experiencing it to understand. And, as El-Kurd writes, the journalists weren’t interested in the voices of adults, who might hold anger toward settlers who looted their homes and jailed their children without charge; the adults’ anger made them imperfect victims.

Telling Palestinian stories to a mainstream audience, El-Kurd has observed, requires the impossible performance of perpetual innocence and respectability. Perpetrators are never named, passive voice is deployed at all times, and “perfect victims” are required. But those don’t exist, he puts forth in Perfect Victims, his second book after the 2021 poetry collection Rifqa, which was named in honor of his grandmother who survived the Nakba. Written in intricate, scathing prose reminiscent of his poetry, Perfect Victims excoriates the absurd politics of how colonized people must appeal to their colonizers. Even those who are sympathetic to Palestine sometimes rely on dehumanizing talking points about Palestinians, in a world that treats their desire for freedom as more dangerous than bombs and genocide. And, as its name suggests, Perfect Victims is an exploration of how victimhood is both assigned and erased—similar to how feminist thinkers have exposed the paradoxical ways rape victims must audition for credibility and justice under patriarchy.

Early in the book, El-Kurd addresses the role of gender in conversations about Israel’s war on Gaza since October 2023. We often see outsized focus on the suffering of women and children in media coverage, but El-Kurd stressed that gender doesn’t shield anyone from harm: “Bombs don’t discriminate, they don’t spare women and children—it’s a wholesale targeting,” he told Jezebel. And under occupation, day-to-day oppression doesn’t differentiate either. There is no childhood for Palestinian children, when girls are subjected to sexual assault by Israeli soldiers performing body searches at checkpoints, or boys are detained and jailed without charge. The global community, El-Kurd writes in Perfect Victims, is indiscriminately desensitized to Palestinian suffering:

We die in fleeting headlines, in between breaths. Our death is so quotidian that journalists report it as though they’re reporting the weather: Cloudy skies, light showers, and 3,000 Palestinians dead in the past 10 days. Much like the weather, only God is responsible—not armed settlers, not targeted drone strikes. … Correspondents kill us with passive voice. If we’re lucky, diplomats say our death concerns them, but never mention let alone condemn the culprit.

In Perfect Victims, El-Kurd observes how victims must be “sanitized and subdued” before anyone can sympathize with them: “One could say the same about sexual assault victims: we must notify the listener that the victim was sober and dressed appropriately,” he writes. Sexual violence researchers have drawn comparisons between political discourse about Israel and Palestine and the tactics wielded by abusers. First, there’s DARVO (deny, attack, reverse victim-offender), which we see when strikes on Gaza schools are justified by Israel’s “right to defend itself.” Then, there’s “orchestrated complexity,” the manufacturing of nuance that always privileges the abuser; this is often achieved by starting in the middle of an abusive situation, when a victim first resists or responds to abuse. Most news reports about Gaza start with October 7 and nothing before it.

“We never tackle things at the root—we’re angry at symptoms but not the disease, which is colonialism and occupation.”

Palestinians are condemned for throwing rocks at Israeli soldiers or, in Edward Said’s case, throwing a pebble at an Israeli military watchtower in 2001, El-Kurd writes. But the voices issuing condemnation never ask why soldiers are there at all. In Perfect Victims, El-Kurd describes this as the phenomenon of starting with “secondly”—that is, only discussing what comes after the initial occupation of a land and aggression against its people. He writes, “Before I threw the rock, they stole my land. Before I picked up the rifle, they shot my loved ones. Before I made the makeshift rocket, they put me in a cage.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-