‘Stranger Things’ Fell for My Favorite Sexist Dead Girl Trope

When writers sentence characters to die, those decisions carry judgment, and we’ve been killing off a caricature of this particular girl for decades.

In DepthIn Depth

Spoilers abound for Season 4, Episode 1 of Netflix’s ‘Stranger Things:’

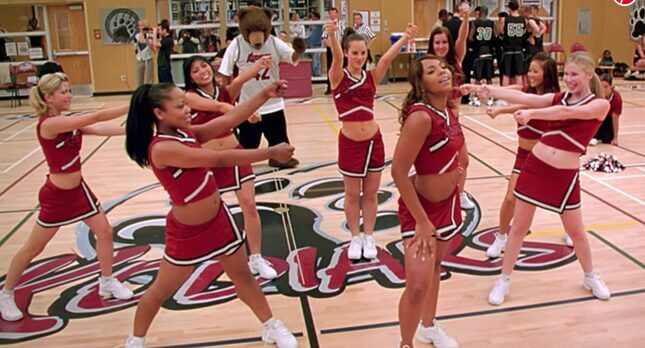

Front and center of a triangle formation stands Popular Cheerleader Chrissy Cunningham. Here, in this particular souped-up pep rally, Chrissy is a character in the latest season of Stranger Things, but really, she could be plopped into any teen movie. She sports Cool Girl fringe bangs and blue eyeshadow, signifying that she’s on the cutting edge of beauty trends—an influencer amongst degenerates and the followers that flank her. She’s beautiful in a heteronormative sense, but not plastic surgery pretty—a perfect girl next door not too far outside the realm of relatability. A walking contradiction, she’s sexy but modest: Her long hairless legs are veiled only by a mini pleated skirt, while her chest is completely obscured by a polyester sweater, save for a necklace that smacks of virginal commitments to the captain of the basketball team. Despite appearing in the first episode of Stranger Things’ long-awaited fourth season in multiple settings and on multiple days, she’s only ever seen wearing her cheerleading uniform. She’s blonde, because of fucking course she is. Also, she’s dead.

In the widely adored ‘80s supernatural adventure show, Chrissy Cunningham (played by Grace Van Dien) is but a blip in the season’s arc—more of a damsel of disappearance than a damsel in distress. The cheerleader, of course, is the first current-day character to be killed off in the new season. And that has a lot to do with the fact that Chrissy—who appears onscreen for less than 26 cumulative minutes throughout the hour and 20 minute-long premiere—has been slotted into a reductive trope that’s been sending cursed ditzy blonde bitches with poms poms to their graves for decades.

Aside from her trauma, which is exploited by something far more sinister than the original demagorgons, Chrissy is given no meaningful identity before becoming possessed, as she’s slammed up against the ceiling at the end of the episode, bones breaking, limbs contorting, eyeballs sucked into their sockets, and blood dripping from every crevice. The cheerleader in this story, as in many stories, is introduced only to die a gruesome death, devoured from the inside out.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-