The Guerrilla Girls On Fighting Art World Sexism Since 1985

In Depth

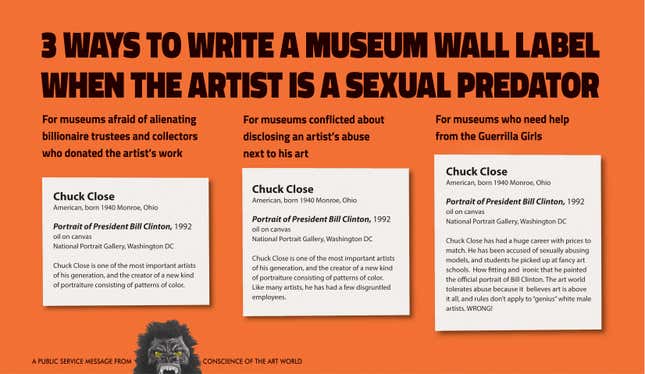

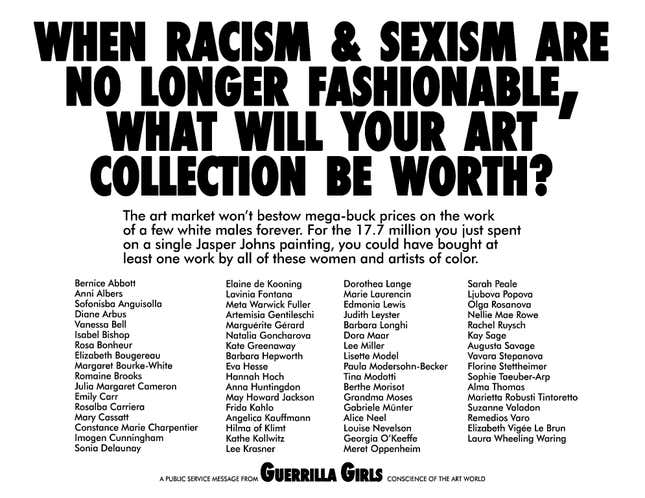

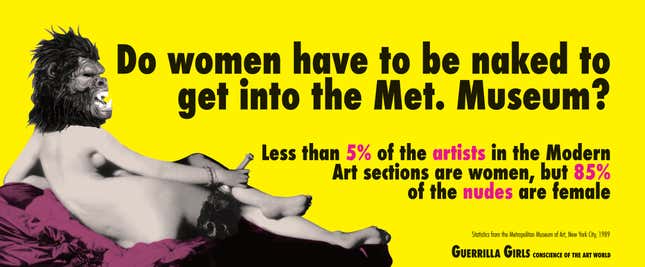

In 1985, a group of artists formed the activist art group Guerrilla Girls, in response to a Museum of Modern Art exhibition of 169 artists with only 13 women and eight artists of color included. The anonymous group—composed mostly of artists using aliases borrowed from famous women artists, wearing gorilla masks to hide their identities—was hellbent on delivering institutional critique to the masses through striking advertisements that poked fun at the art world establishment while also calling out its deeply entrenched sexism and racism. The group’s latest book, Guerrilla Girls: The Art of Behaving Badly, encapsulates over three decades of art world interrogation, from their early, minimalist graphic posters that asked if “women have to be naked to get into the Met?” to expansive dissections of museum diversity commissioned by museums themselves.

The past few years has been a watershed moment for art museums, as activist groups and curators have called out institutions like the Whitney and the Guggenheim for racist conduct and the inhumane business practices, and union drives for embattled art workers have popped up at museums like the New Museum and MOCA. And many of the issues Guerrilla Girls have raised for the past three decades, from the racial and gender diversity of museum exhibitions to the whiteness of Academy Awards winners, have only become more mainstream in the last decade. Founding members who go by the names Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz spoke to Jezebel about the group’s approach to using humor, how the art world has evolved since they began, and the perils of art market tokenization.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: When this group began in the early 1980s, did you two think you’d still be out here in 2020 fighting the same art world discrimination and sexism?

FRIDA KAHLO: The short answer is, no. [Laughs] We were just angry and we decided that we wanted to do something about it. We put up a few posters and they worked, and we listened to people’s responses to them and got ideas for other posters.

KATHE KOLLWITZ: We also never thought that we would basically be using the exact same strategy. Finding a new way to disrupt things by using, you know, crazy visuals, disruptive headlines and killer statistics. We work under the same paradigm as our original idea. Who thought that would still work? But it does.

Does it feel disheartening at all that you still can use the same strategy?

FK: The fact is the situation has changed and the art world has evolved and the problems have evolved, so the strategy is not being applied to exactly the same problem. First, it was a question of changing people’s consciousness to get them to realize the art world was not a meritocracy. Now we can focus on the structure of the art world and the institutional racism and sexism that exists.

The book notes that the group was initially criticized for being whiny and overly negative. What was the conversation like in the 1980s art world about institutional critique and about art world diversity?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-