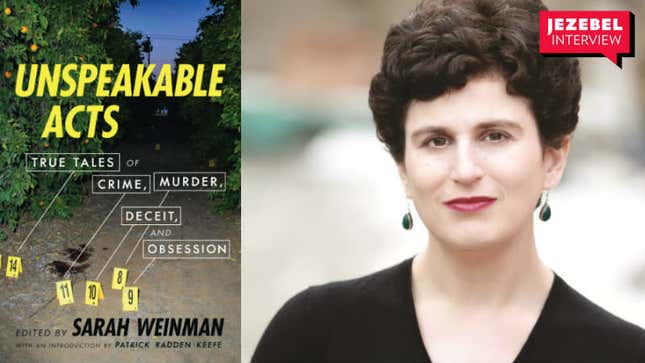

In the midst of true crime’s boom, when people have hundreds of articles, prestigious TV shows, and shoddily reported podcasts to choose from to get their crime fix, Sarah Weinman’s new collection aims to cut through the noise. In the new book Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit, and Obsession, author and reporter Weinman brings together over a dozen of the best true crime stories in the past decade or so from writers like Rachel Monroe, Pamela Colloff, and Michelle Dean.

There are stories about the horrors of US Customs and Border Protection and how misguided blood-splatter technology became legitimized, plus engrossing narratives about victims of gun violence and con artists. And rather than stick to scandalous stories about violent serial killers and battered dead girls, Unspeakable Acts moves the needle closer to a version of the genre where crime is systemic abuse, baked into the work of institutions designed to protect us.

Jezebel spoke to Weinman about how she chose the stories in Unspeakable Acts, the importance of messy crime narratives, and reimagining what makes a true crime story. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

JEZEBEL: How did this collection come together?

SARAH WEINMAN: I’ve been thinking about a collection like this really since I think 2016 when I wrote a piece for The Guardian, which I reference in the introduction to Unspeakable Acts, talking about what was going on with what I would characterize as the “true crime boom.” I wanted a collection that best represented the text pieces that were coming out of the so-called boom, which I date to when the first season of Serial, the podcast that Sarah Koenig did about the murder of Hae Min Lee and the possibility that Adnan Syed didn’t do it, became such a cultural phenomenon and an audience that didn’t think of itself as a true crime audience was really responding to it. As is often the case with cultural phenomena, it spawned other books, documentaries, podcasts, and feature articles.

I think what I felt, especially as a crime writer myself, [is] that the pieces that I most responded to were not necessarily sticking to traditional true crime narratives. They were kind of bleeding the lines a little bit; they were not so linear, they didn’t necessarily follow a Law & Order narrative, they didn’t prioritize the trope of the dead girl. They were talking about bigger issues, systemic issues of criminal justice. I wanted to put together my dream anthology and I was lucky and able to do that.

Serial was so interesting because, as you said, it was unconventional crime reporting. It didn’t have a definitive end, certain sources weren’t even available, and it was kind of personal and intimate because it was a podcast. What do you think accounts for this true crime boom? Why are people who don’t necessarily think of themselves as true crime consumers are gravitating towards the genre?

As long as this country has existed people have had an appetite for crime stories. It sort of waxes and wanes in terms of highbrow and lowbrow. With books, people keep coming back to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and with documentaries, I think they go back to Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line. What’s different now—and I think Serial really drove this home—is that there was this real participatory, interactive element to it. You had all these message boards and Reddit subthreads and people going by the houses of possible suspects and inserting themselves into the narrative. There was this real interplay between what the professionals were doing and what the so-called amateurs were doing.

I’ve been watching the HBO documentary version of I’ll Be Gone in the Dark which is a retelling but also an extension of Michelle McNamara’s book published posthumously. She herself was a very talented and gifted crime writer who was able to gain the trust of law enforcement professionals, but she also was part of a community of amateur sleuths and they trusted her as well. She was kind of the nexus point between the professionals and the amateurs, all with a communal interest in solving this heinous spate of serial killings. As we now know, the culprit was apprehended and has now pleaded guilty. Even though it wasn’t perhaps a direct result of McNamara’s work and her book, I do still feel like all that work was a catalyst.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-