Labor of (Someone Else's) Love: My Summer Planning Weddings in Italy

Latest

When I was 20, my college’s funded internship program wrote me a check for $3,000. Instead of hunkering down in an LA production office to slog through slush piles—as a film major actually invested in her future would probably do—I pursued an internship that cashed in on my incomplete Italian minor and weird penchant for institutionalized cross-cultural romance rituals. I would plan weddings in Italy. It would be very Liberal Arts.

The boutique events company was based in a small Tuscan town stuck between the medieval metropolises of Florence and Pisa. I took a plane, a shuttle bus, and two trains to reach it, arriving in the dry dark of nightfall. A cab driver dropped me off after a brief, silent ride. My summer rental was a sparsely furnished two-bedroom with more space than I would know what to do with, for which I’d overpaid. “Buonanotte,” I told my cab driver. “Grazie.” Then I was left alone with my expensive and still Italian rooms. I had no sense of where I was other than what I’d seen in the shallow slosh of the cab’s headlights.

It was past midnight, but my circadian clock was striking a cool 7 p.m. I was wide awake. Within a few hours, I was sitting on the too-big, dusty kitchen floor, cradling my computer and a defunct modem in my lap, choking back panic. I was in a strange town and a strange country, and I couldn’t reach anyone I knew. I climbed into bed, cried a lot, and watched every episode of 30 Rock I had saved on my hard drive until sunrise. And when day broke, I wandered outside, trying to push back the absurd but awful feeling that I would never see anyone I loved ever again.

This was my first time seeing Italy. The apartment buildings were squat and smooth and the colors of the earth: chalky pastels, achy reds. Clothes were drying on cramped patios and strung between windows, hanging motionless in the hot, heavy air. It was still early. I walked down my street and didn’t see a single person. To my left were the apartment buildings, and to my right was Tuscan countryside, tons of it, stretching out in pale thirsty grass to a bunch of real-deal vineyards fringing purple hills.

I was standing in the middle of the street, open-mouthed in sleepy stupor, when I heard my name. A woman pushing a baby carriage was rounding the corner, waving at me.

Running a wedding-planning operation out of a remote Tuscan town meant that my boss, Alana, spent most of her workday in the car. Every morning, I climbed into the back of her teeny-tiny Fiat so she could hand me her infant through the window. I’d strap the baby into her carseat and make poor attempts to entertain her while she cried the whole ride to one of her grandparents’ houses, where she’d be dropped off for the day. Then I’d clamber back up front and ride shotgun beside Alana for hours on end through the sun-flowered country.

Alana was a force. In her late 20s, she was running her own business out of her beautifully decorated, ultra-modern little two-story apartment, which was only a few miles away from the one in which she’d grown up. On our car rides, I looked out my window while listening to her raucous, rolling Italian; she shouted good-naturedly into her headset at caterers and florists, breezing through 15 different conversations in as many minutes. She wore smart, clean-cut dresses in either black or gray, changing into heels once she’d parked after driving in Pumas. She had a great big laugh, obstinate opinions on life’s minute details, and buoyant, unselective affection rolling off her in waves. I admired her very much.

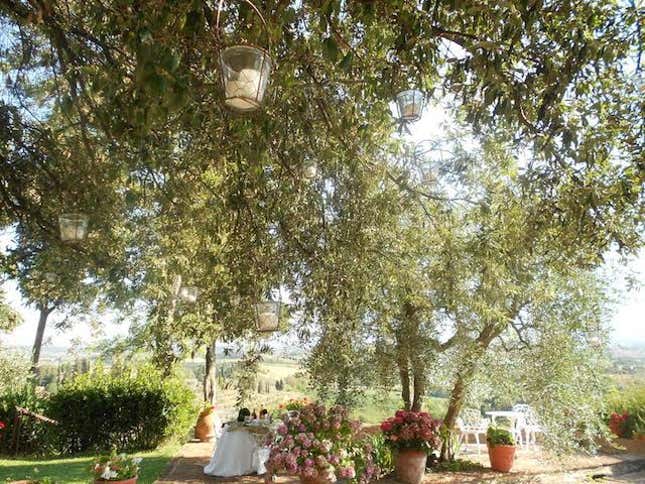

We drove to wedding venues. I let Alana handle the fast, loud negotiations with proprietors while I wandered around alone, taking pictures. It was one of my projects; Alana had charged me with designing location one-pagers to fire off to potential clients. I photographed infinity pools hanging off the lawns of 17th-century villas; the windswept, riotous greenery swamping old castles; stately rooms with antiques in creaking leather and crushed pastel velvets, saved from stuffiness by sweeping wide windows letting in the summer light.

Back at the office, I downloaded my pictures and emailed panicky American brides about their floral arrangements. Since the office doubled as Alana’s home, she rarely let me leave for the night without dinner. We made panzanella salads with the basil she grew on her patio, dancing around each other in the kitchen, the baby switching from my hip to hers and back again. We drank from a bottle of unlabeled wine from her father’s local vineyard, the front door flung open to the late-setting sun.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-