A History of Bedbugs Driving Us Insane

In Depth

No creature provokes such astronomical panic while presenting such infinitesimal physical danger like the bedbug, an insect linked to no diseases whatsoever. Bedbugs irritate, certainly: they bite your legs, disturb your sleep. But the extreme fear of them—the sense of shame that surrounds a bedbug infestation—stems not from anything rational, but from the instinctive sense that something debased about us has been confirmed.

“Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin,” Darwin once wrote. He was noting the pattern of animal descent he described in On the Origin of Species, but we also bear our vestigial lowliness in the litany of bugs that randomly cling to the human body: lice, scabies, fleas, ticks, and of course, bedbugs. These pests joined us at our simple beginnings, and they remain the most uncomfortable of all equalizers. They ride us like any other member of the animal kingdom; they infest us, feed upon us every day.

Maybe it’s surprising that bedbugs remain such a powerful drain on our mental resources. Bedbugs have been the focus of human ire ever since we emerged from the antediluvian sludge where it’s likely that these insects laid in wait, born hungry for a fresh meal. We’ve exerted an immense amount of brainpower on their eradication. And yet, despite our best attempts, we cannot thwart a nature that made bedbugs so damningly hard to kill.

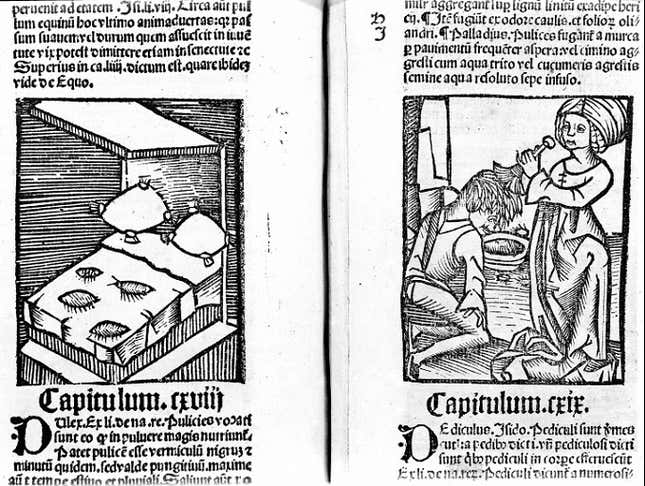

The bedbug has been with us since near the beginning of recorded time. The fossils of the bugs have been found at Egyptian sites, likely dating between 1352-1336 BCE; written references seem to exist as early as 432 BCE. They were described in detail by Pliny the Elder, the great Roman naturalist, in his encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia. Pliny simply called them cimex—Latin for “bug.” It was the tireless taxonomist Carl Linnaeus who would finally give them their modern name, cimex lectularius, which means “bed bug,” or “bug of the couch.” But Linneaus was a creative man, descended from sternly resourceful Lutherans. He didn’t see the bugs simply as foes, but also suggested instead that they might be used to ease earaches. References didn’t come only from the West, either—as early as the seventh century, China too recorded the pestering presence of the bug.

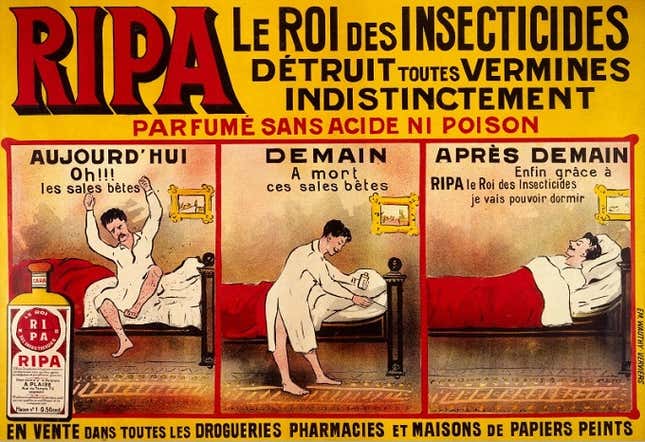

Later civilizations grew less committed to taxonomy and more to annihilation. Nearly any and all poisonous substances that science or nature has gifted us have been used in our never-ending battle to eliminate the blood suckers. In her book Infested: How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World, Brooke Borel traces remedies dating as early as the seventeenth century. A 1946 entry in the Journal of the New York Entomological Society noted the discovery of a 1756 advertisement for “Oyl of Turpentine” sold by a furniture maker, advising that the “spirit of turpentine applied to bed-steads and those places where bugs breed, and lodge, effectually destroys them, and prevents them from harbouring those places where it is applied.”

BedBug Delousing, Hortus Sanitatis, 1499. Image via Wellcome Collection

Turpentine might be the least interesting—and likely the least dangerous—method that humans have used to eradicate the bugs. Eighteenth-century philosopher John Locke preferred a more natural treatment: he suggested that placing dried leaves from kidney beans under the bed would keep the bugs from snuggling into the bed. But in general, poison was the tonic of choice: Mercury, Zyklon B, and good, old-fashioned arsenic have all been employed against bedbugs. And when poison proved useless, fire was the element. In the nineteenth century, smoke from peat fires were used to fumigate Victorian homes, and blowtorches were recommended in the early twentieth century. The human search to eliminate the bedbug was so ever-persistent that, in the 1920s, the U.S. Patent Office created a special designation to track bedbug-related inventions.

And yet, despite these efforts, the unwelcome bedfellows couldn’t be stopped. Their thirst for slumbering human limbs was too strong for even a housewife’s homemade potion of mercury and arsenic. It was the discovery of DDT’s (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) insecticidal abilities that would stop bedbugs in their disgusting tracks. DDT wasn’t exactly a new discovery in the 20th century—it had first been synthesized in the 1870s—but in 1939, Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller discovered that the compound could be weaponized against bug populations.

And so, in our zeal to eliminate insects, humans blanketed DDT on nearly every inch of earth in the Western hemisphere. DDT proved incredibly effective; it was used to control the spread of insect-borne infectious diseases during World War II, keeping malaria, typhus, and other diseases that had previously wreaked havoc on soldiers in tight, unhygienic spaces, at bay. It was so effective in World War II that, in the post-war period, it was widely used as in the United States as common insecticide. DDT was a kind of magical invention: colorless and nearly odorless, it allowed crops to bloom without infestation and allowed an entire generation to enjoy the leisurely spaces of backyards.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-