We’re All Trapped in Instagram’s Digital Mall Now

Latest

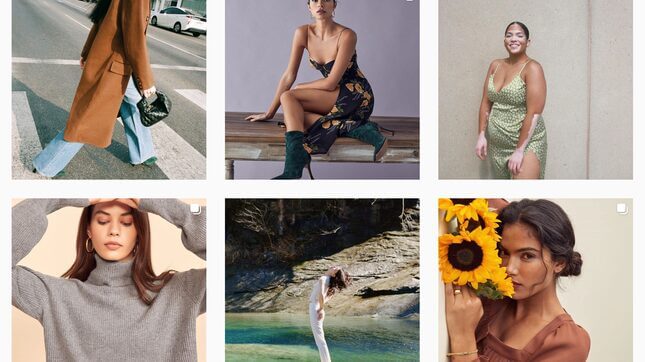

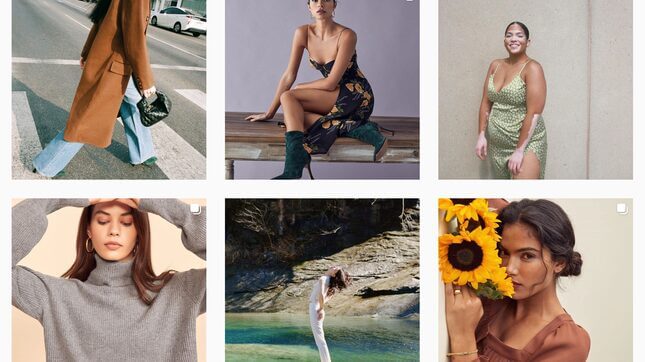

Last week Instagram users trying to seek out the most important part of the app, the activity feed, were likely confused to find that the homepage’s icons were not where they used to be. Where a heart icon in the bottom right corner once led users to see who has favorited their posts, now there was a tiny bag that led you to Instagram’s new shopping page. The app was preying on every user’s muscle memory well-tuned to its layout. “Instead of looking at who is favoriting your posts, why not shop?” Instagram seemed to say, loud and clear. The app had reached its final, dismal form; QVC for a digital age, influencer-approved favorites hanging in the windows of the newly opened digital mall.

That Instagram would pivot fully into becoming a shopping app (not to mention clinging to the possibility of being a TikTok competitor, with its dreadful “Reels” page where the search function used to be) isn’t totally shocking. The shopping page placement had been rolled out as a test in July and was only universally adopted in the app this month. Since its inception, Instagram has gone from being a cute, banal photo-sharing app to a shopping app in Facebook’s growing arsenal of websites designed to mine user data to better sell ads back to them. But the app’s blatantly consumerist makeover comes at a time when Instagram’s potential was just being illustrated by its users.

When it debuted in 2010, there was a welcome minimalism to Instagram’s photo-first approach in the shadow of text-heavy Twitter and crowded Facebook, which by then had lost its college and high school exclusivity. But Instagram was also cooler, with its easy to use retro filters that gave a warm, Polaroid glow to otherwise boring photos, a move borrowed from the app Hipstamatic. It was detached from Facebook’s noisy stream of relationship updates, job announcements, and wall posts. You could still upload a roll of party photos to Facebook the next morning and painstakingly tag each of your friends for the whole school to see, but Instagram understood that the age of the digital camera was over. Nothing on that dingy Canon pocket camera was going to be as pretty and hipster chic as anything you could post on Instagram, captured and uploaded at the moment by a smartphone. It’s no wonder Facebook acquired the app two years later for $1 billion.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-