I Let 3 Sorority Rush Consultants Read My Life For Filth

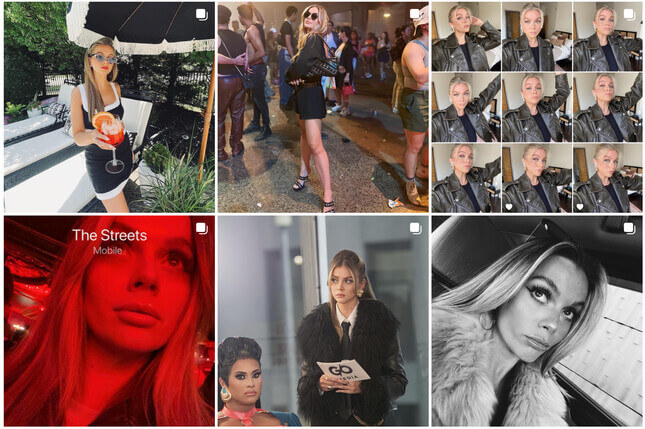

Each Bama Rush consultant critiqued my Instagram, my small talk, and my Doc Martens in a bid to get this 29-year-old woman rush ready.

In Depth

Illustration: Vicky Leta

The year is 2012. Lo-fi is still the Instagram filter of choice; the “Harlem Shake” will soon become the viral dance du jour; Jenna Lyons is not yet a Real Housewife. I am a freshman at Ohio State University (pre-pretentious “the”) where I spend much of my time trying personas on for size and breaking my own heart in futile attempts to force one of them to fit. I teach myself to smoke cigarettes and go to shows at Newport Music Hall alone. I dye my hair black and furrow a brow at cloying poetry at Cafe Kerouac. And for several Thursdays, I take pulls from a bottle of cereal-infused vodka and let boys in polo shirts feel me up on a sticky dance floor. Multitudes, I tell myself. Inside me are hundreds of women—all of whom long for more than what they currently have: purpose, passion, and more than anything, more people to call a friend.

Back then, there was at least one foolproof way to achieve the latter at Ohio State: Join a sorority. Only I was prideful to the point of arrogance, and admitting to myself that I was desperately lonely seemed as lame as trying to light your own cigarette outside a club with bands you don’t recognize on its marquee. Ultimately, the dress codes and forced mingling—and some stuff I’ve since addressed in therapy—kept me squarely in the women’s, gender, and sexuality studies department until graduation day.

Despite Gen Z’s tendency to balk at almost every institution and tradition, the Panhellenic system seems to have as much staying power as my rush ruminations. In 2021, as the world reeled from a pandemic, the #BamaRush hashtag was viewed on TikTok over half a billion times globally. It became, as the New York Times wrote, must-see TV. A year later, Jezebel wrote about its return to relevance in 2022, calling it a continuation of “homogeneous white feminine aesthetics of enforced social hierarchy.” Judging by this year’s similar social media content, the culture hasn’t changed—even if some candidates have become more frank about the system’s offenses.

In recent years, the recruitment process has sparked conversations about queerphobia, classism, racism, and the elitism of Greek life, but the Panhellenic system has yet to evolve as much as its prospective participants might have. Non-binary people remain excluded from the process, and a certain type of participant (heteronormative) is still rewarded more often than the alternative. Nevertheless, rush persists.

The industry surrounding it does too. Over the last decade, rush consultants have capitalized on young women’s attempts at achieving social acceptance among their peers; with some charging up to thousands of dollars to advise on what to wear, how to act, and who to project as during the process. Per new reports, business is booming.

Now that I’m more amenable to the fact that life is nothing if not a series of unpleasant, unavoidable exercises that, at times, involve being perceived, I sought out the aid of three renowned rush consultants to assess the current me on the criteria that once stopped 18-year-old Audra from entering the recruitment process: social media presence, conversation, and wardrobe. Enter Trisha Addicks, Sloan Anderson, and Lorie Stefanelli—all of whom were featured in HBO’s Bama Rush and boast solid success rates (read: all of their clients have gotten a bid, even if it’s not the one they wanted).

Is 29-year-old Audra any more rush-ready than the 18-year-old iteration? You decide!

Conversation: Be a Brooke, Not A Sam

Talking to people is daunting, and maintaining interest in what others have to say is, occasionally, impossible. Unfortunately, both are crucial parts of rush. How does one overcome this? Per the advice of most consultants, by creating a script. Some consultants—like Anderson, the founder of Getting the Bid–have explicit topics to avoid. If you watched Bama Rush, you likely know them as “The Five B’s”: Boys, Booze, Bible, Bucks, and Biden. Basically, anything that’s oppressed people is strictly off-limits.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-