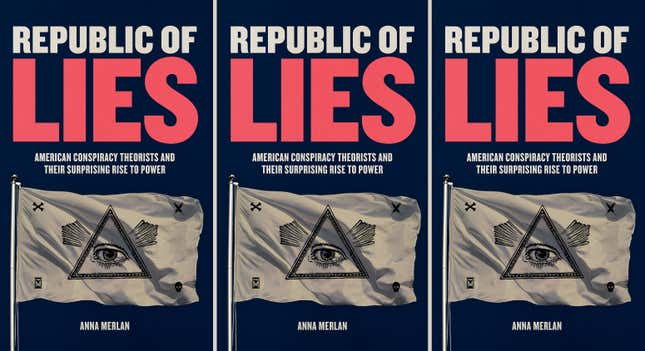

Image: Henry Holt and Company

In my forthcoming book Republic of Lies, I spent a lot of time thinking about the primacy of conspiracy theories in America, and talking to people involved in a variety of conspiracy communities. In this section, I attended a rally for Pizzagate believers across the street from the White House, and talked to them as they waited for David Seaman, a star in the movement, to take the stage.

“We need an investigation,” a woman named Angel told me patiently. A casino worker in her mid forties, she’d driven all the way to DC to hold a neat hand-lettered sign featuring a picture of a Comet staff member’s toddler daughter, her hands taped to a table with heavy white masking tape. “We can’t call people innocent without an investigation.”

Given that she believes the federal government is involved in the sex-ring cover-up, who should do the investigating? I asked her.

“We need an unbiased investigator,” she said, just as patiently.

Like a lot of people I spoke to, Angel was fairly certain there are no longer any children in the basement or back rooms of Comet Ping Pong.“I’m sure they’ve cleaned themselves up to the point where if you, look, there’s nothing there,” she told me.

“They use the word ‘conspiracy’ as a catchall to delegitimize any questions about anything,” complained a woman standing next to Angel wearing a black “Benghazi Matters” T-shirt and an NRA hat. Refusing to tell me her name—I was instructed to call her “LaLa”—the woman went on, vacillating between rage at the press and a slightly irritable but basically kind desire to set me on the right path.

“This is why Trump has emerged as someone people trust,” she said. “He calls things out as he sees them. And maybe these conspiracies aren’t just theories, they’re actually truths? That have been going on since the beginning of time?”

“Amen,” Angel responded forcefully. “Having sex with babies and children, they say it gives them power.” She shook her head. “They get what they want in life.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-