In the early 2000s, teen girls were constantly at war with one another.

Stories of girl-on-girl bullying filled the self-help section of every Barnes & Noble. In 2003’s Please Stop Laughing At Me, writer Jodee Blanco recounted how as she was cast out from social cliques as a teenager and once found her shoes thrown into a urine-filled toilet bowl by mean girls. Odd Girl Out identified a inner aggression in girls, one that had them constantly competing with each other in “a perverse game of Twister.” While Phyllis Chesler’s Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman noted that women “judge harshly, hold grudges, gossip, exclude, and disconnect from other women.” In 2002, the New York Times Magazine ran a cover story with the title “Girls Just Want to Be Mean,” quoting researchers who found that girls treat “their own lives like the soaps, hoarding drama, constantly rehashing trivia” and adore traveling in predatory packs for “entertainment value.”

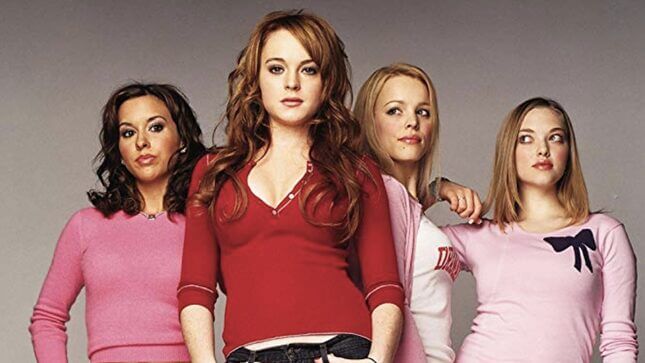

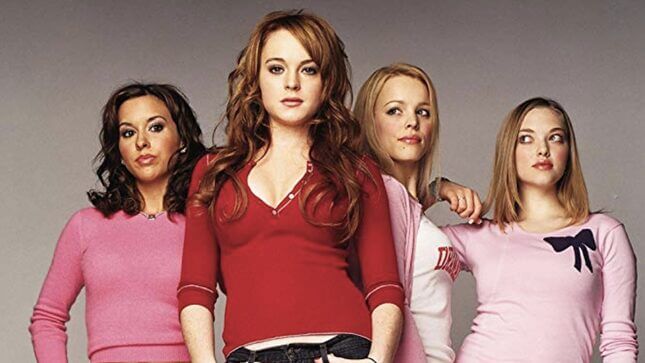

But one book emerged particularly triumphant in a sea of writers dissecting teen girls’ wrath for each other: Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends and Other Realities of Adolescence. Published in 2002 by teacher-turned-writer Rosalind Wiseman, Tina Fey used the book for the basis of her 2004 film Mean Girls, cementing high school bitchery in the teen comedy canon. “This was something I feel that I could write about,” Fey told the website Blackfilm in 2004, about adapting the book to film. “And because it was about girls. And it was nasty and violent. And that appealed to me,” she added.

The book was more than just a chronicle of adolescent nastiness; it further solidified an image of the all-American girl as a frivolous cipher in a miniskirt. “In this book I will teach you to develop or restart your girl brain,” Wiseman writes early on in Queen Bees and Wannabes. “If you can learn how to be her safe harbor when she’s in the midst of Girl World conflicts, your voice will be in her head along with your values and ethics.” Wiseman’s book was transparently written for parents, specifically those exasperated by their daughters. The teen girl, in Wiseman’s world, was constantly walling herself off from her parents, turning away from the authority of her home and towards the authority of girls she identified as Queen Bees, the very girls who ran the cliques at school.

This is Queen Bees and Wannabes claim to fame: a dissection of how cliques work so extensive it rivals the Tony Soprano dynasty. There’s the Queen Bee (the leader, of course), the Sidekick, the Banker (the gossip keeper), the Wannabe, the Torn Bystander, and so on, all of whom move in a predatory pack that can kick out and isolate a girl the moment she refuses to obey its arbitrary rules.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-