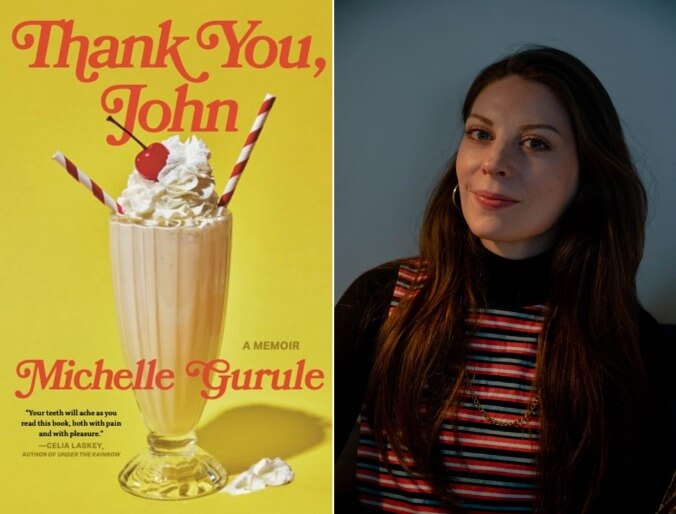

‘Thank You, John’ Is About Writing, Debt, and Keeping Sex Work Secret From Everyone but Family

"Sometimes I can trick myself into believing the stigma is gone... but then I step outside my progressive bubble and get reminded how quickly the old narratives surface," debut author Michelle Gurule told Jezebel about her past as a sugar baby.

Photo: iStock BooksEntertainment

“I could compromise access to my body for the greater good of my body,” Michelle Gurule writes in her debut memoir Thank You, John, as she, a then-24-year-old college student, decides to have sex with John, a patron of the Denver strip club where she works, for money. She’s one of the club’s less skilled strippers, and yet the job is “the only one I’d ever had that actually sustained my being alive.” But that income isn’t enough; Gurule’s quality of life is tenuous at best. She has a mouth full of cavities she can’t afford to fix, faces $35,000 and climbing in student loan debt, and sleeps on the couch in a two-bedroom apartment she shares with her mother, sister, and nephew. By becoming a sugar baby—in this case, getting paid to spend time and be physically intimate with John—Gurule hopes not only to improve her own life but also to pull her entire family out of poverty.

There are other compromises besides her body: honesty and socialization, as fears of judgment prevent her from telling anyone outside of her family about her work; joy and health, when the anxiety over each new sugaring decision leads to vision-altering migraines. The balancing act that Gurule attempts is the genesis of Thank You, John, which is just as much about sex work as it is about the difficultly of attaining financial security in America. It’s about attempting to put personal and familial well-being ahead of cultural expectations—and not always succeeding. It’s about how the people who know us best (in this case, Gurule’s parents, sister, and nephew) can anchor us in our most challenging moments through humor and acceptance.

Thank You, John joins a series of books written by and about sex workers over the past few years, including Isa Mazzei’s Camgirl; Chris Belcher’s Pretty Baby; and The Holy Hour: An Anthology on Sex Work, Magic, and the Divine edited by Molly B. Simmons and Emily Maire Passos Duffy, and Gurule said these books all “engage with the complexity of our experiences rather than flattening them into the tired binary of empowering versus disempowering.”

“Sex work looks different for everyone,” Gurule, now 34, told me in a recent conversation, “and there are countless ways to inhabit that role.”

With Thank You, John—which takes its name from the phrase Gurule’s family members shouted whenever she brought home to-go meals after dining out with John—“I really want this book to complicate the way we talk about sugar babying,” she said. “In the cultural imagination, sugar babies are often flattened into a caricature: young, pretty women chasing handbags and beach resorts. [But]…for me, and for many others, it wasn’t a glamorous choice at all. I wasn’t interested in luxury so much as trying to secure some stability.”

Read on for the rest of our conversation (which has been edited and condensed for clarity).

If you could go back, would you have made a different choice around identifying yourself publicly as a sex worker while you were doing it?

When I had my first essay about sugaring accepted back in 2019, I realized I didn’t want people to find out about my sex work through a publication, so I took this trip to Denver where I basically went friend to friend, confessing that I’d been a sugar baby. And honestly? Nobody cared that much. Which was both a huge relief and also a little destabilizing, because I’d spent years carrying all this shame; lying, hiding, and making myself sick with the secrecy. After that trip, I wondered if I’d been a fool to keep it so guarded. I do wish I’d been more honest earlier, but at the time, I truly didn’t know how. I had so much shame tangled up in it that honesty just did not feel possible.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-