Aziz Ansari Effectively Interrogates Others, But Not Himself, in Netflix Standup

EntertainmentMovies

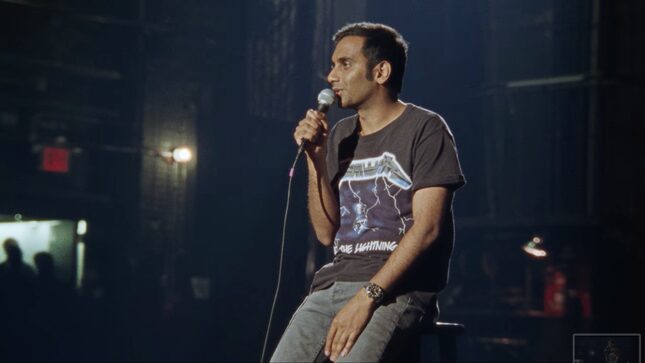

Screenshot: Netflix

Aziz Ansari begins his new Netflix comedy special Aziz Ansari: Right Now, with an admission. Not of guilt, but of the fact that he’s spent the past year thinking a lot about the sexual misconduct allegations made against him in a story published by Babe.net in 2018. “I haven’t said much about that whole thing, um, but I’ve talked about it on this tour,” he says, sitting on a stool on stage at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. When the camera pans to the audience as he walks on, it looks like a full house. “There’s times I felt scared. There’s times I felt humiliated. There’s times I felt embarrassed. And ultimately, I just felt terrible that this person felt this way.”

“This person” is the woman who said Ansari ignored her verbal and nonverbal cues during a first date at his apartment. His voice is low, pacing measured. It’s different from the Ansari who, in prior stand-up sets, used to jump around on stage and shout for emphasis and was known for his shock-comedian character Randy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-