How Disney's First Woman Animator Broke Into the Boys' Club

In Depth

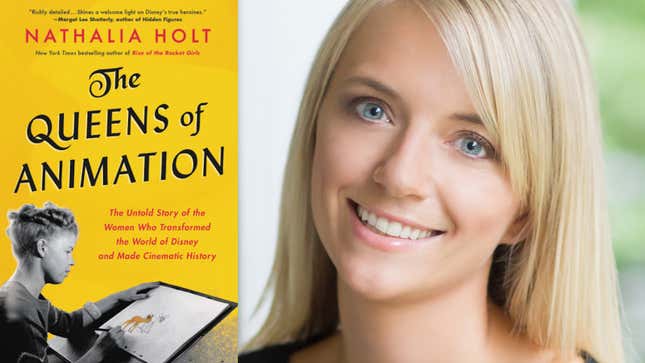

Below is an excerpt from The Queens of Animation. In the book, Nathalia Holt traces the careers of the women who broke into the vaunted animation department at Disney in its earliest days, shaping landmark elements of the company’s history from Fantasia’s “Waltz of the Flowers” to the look and feel of Dumbo and Bambi. Holt—who is also the author of Rise of the Rocket Girls, about the women who worked as “human computers” at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the dawn of the space age—follows their influence all the way through to the blockbuster Frozen. This despite many, many challenges and assumptions, exemplified in this excerpt by the literal boys’ club on the roof of the building where they worked.

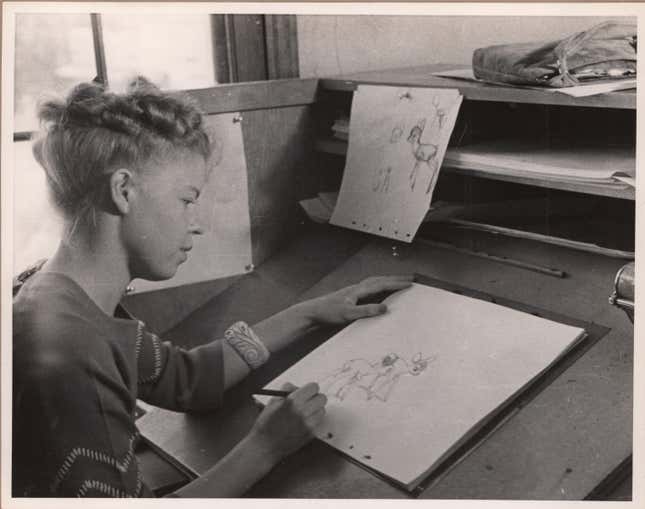

The artists working on Bambi gathered around a pile of sketches. No one knew where the drawings had come from, but all agreed that they were terrifying. The hunting dogs seemed to leap off the page with thick, muscular bodies and arresting eyes. In the sketches, the snarling beasts corner the doe Faline. Bambi then charges in, using his antlers to fend off the vicious animals in scenes that burst with action: the dogs’ backs arch in pain and Bambi’s antlers are framed perfectly in each shot to highlight their strength. The artists looked at one another and asked, “Who did this? Whose drawings are these?” The animators all assumed that the mystery artist was a man. Still, no one took credit. It seemed as though the sketches had fallen from the sky. Then Retta Scott walked in. Here was their culprit: not a man at all but a young woman with blond curls piled on top of her head, and a host of ideas on how to make the attacking animals even more frightening.

Walt Disney Studios had just moved into its new home in Burbank, and for Retta the move had not come a moment too soon. The story group working on Bambi back on Hyperion Avenue had been relegated to a small outbuilding on Seward Street that they called, not affectionately, “Termite Terrace,” as its walls had started curving inward, literally crumbling in place. The Burbank studio, in contrast, was like a palace with its three-story Streamline Moderne design. Walt had personally worked on the architectural plans, helping to create a massive eight-wing building, formed from two side-by-side H- shaped structures with plenty of windows, so that natural light flowed into the offices. The animators and concept artists worked on the ground floor; directors, background, and layout artists on the second; with the story department and Walt’s office on the third floor.

If you took a private elevator up to the roof, however, you entered an entirely different world. Getting off the lift, one was confronted by a mural of fourteen nude women surrounding a single man on the wall next to the door. Known as the Penthouse Club, the space offered a bar and restaurant, barbershop, massage table, gym, steam baths, beds, billiard and card tables, as well as a large uncovered area popular for nude sunbathing. The exclusively male club required substantial dues and a strict selection process to join. An employee had to make more than two hundred dollars a week, a level attained by only a small number of animators. It was a new era of elitism at the studio, one that rankled for many of the artists, who had previously viewed their group, crammed together in ramshackle buildings on Hyperion Avenue, as a family.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-